Music and Mao

New Work by Department Chair Lei Ouyang

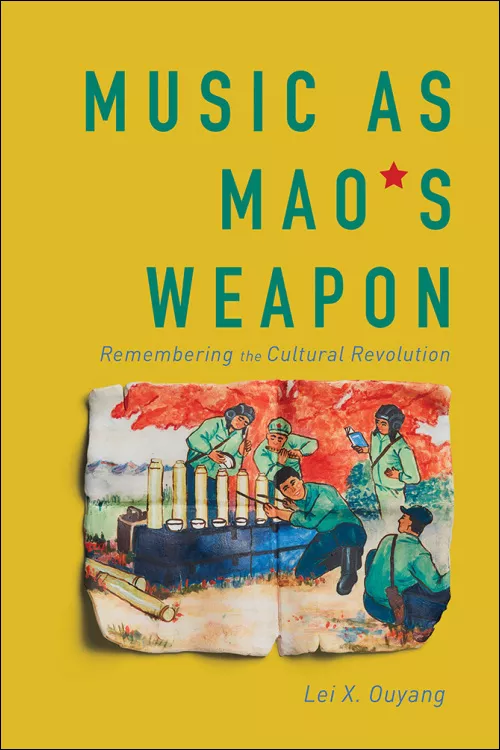

The words “Cultural Revolution” invoke vivid imagery in the minds of people around the world, especially for those who grew up during its peak and those experiencing its legacy today. They recall hats adorned with red stars, posters decorated with the face of Chairman Mao, and uncountable rows of faces standing at attention to the backdrop of the Chairman’s words. While this imagery holds true for those living in China between 1966 and 1976, another aspect of the Revolution is often overlooked – the accompanying sounds. It is these sounds and their part in the lived experience of the Cultural Revolution that Swarthmore’s Professor Lei X. Ouyang examines in her latest work, Music as Mao’s Weapon: Remembering the Cultural Revolution (University of Illinois Press, 2022).

As we sit in her office, the heavy subject matter of our conversation is juxtaposed with the bright sun of the winter afternoon shining through the window. “[This book] is about understanding how people experienced the Cultural Revolution and remember it,” Ouyang says. When asked about her inspiration, Ouyang speaks of her time as a graduate student in China, recounting a lunchtime conversation with an advisor about music composed during the Revolution. Her advisor spoke of “how significant [the songs] were politically and on a cultural level as a lived experience.” Interestingly, these songs had yet to be a topic for scholars based in China, which left Ouyang in an unique position as an Asian American. She had an inherent political and emotional distance from the Revolution as an American; however, she also had “opportunity for a closer connection” as a Chinese American raised in a bilingual family. “The lens of the ethnographer is an important aspect of the work,” Ouyang notes, “My identity was … omnipresent.”

It might seem strange to study such a visceral and challenging time in China’s musical history and Ouyang shares that she often hears the question, “Of all the music in China’s history, this is the worst music ever! Why would you study this music?” Her answer: “moments of humanity can be re-accessed through this music, lots [about the time period] can be accessed that are difficult to do so through other means.”

On a larger scale, there is an inherent sense of interdisciplinarity that Ouyang hopes her audience, whether they be Swarthmore students or scholars at large, can observe through her work. Those coming of age during the Cultural Revolution grew up in an era where politics and music were so intertwined that it was impossible to understand one without understanding the other. In many fields, interdisciplinary work is emerging as a way of forging unlikely connections that lead to a deeper understanding of the area being studied. Look no further than Swarthmore and the wealth of interdisciplinary plans of study offered to realize the importance of such disciplines.

I asked Professor Ouyang what her favorite part of working on the book was. She sits for a second before responding, “I guess favorite isn’t the word I would use, but I was really grateful and humble that folks took me on their journey of reflection,” after all she notes, “[it is] a challenging topic, we’re dealing with generations of trauma.”

Since the publication of Music as Mao’s Weapon, Ouyang has shifted her focus to Asian American studies, taiko, and the overall Asian American experience. Looking back at her publication, she speaks with an air of accomplishment, “This [book] was a long time coming … I’m glad that I was able to see it through to this stage and I hope that I’ve honored the people that I’ve worked with.”

Those interested in Ouyang’s work can find the book at the University of Illinois Press as well as at any local bookstores carrying it.

On Friday, September 8, Ouyang’s book will be featured together with two recent books by Swarthmore Alumni and fellow ethnomusicologists Marié Abe ’01 and Shalini Ayyagari ’00. Abe, Ayyagari, and Ouyang will be in conversation together with noted ethnomusicologist Deborah Wong of UC Riverside and Swarthmore’s own Steven Hopkins (Religion & Asian Studies). The book launch and discussion will be held at the Inn at Swarthmore from 4:30-6pm with a reception to follow. More information can be found on the Aydelotte Foundation webpage.