The Spectacular Cinematic Utopia of Oz

Essay by Jayho So '26 for American Narrative Cinema Course

One of the most iconic sequences of the genre defining The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) is the extended scene in which Dorothy Gale (Judy Garland) opens her house door and enters the lavishly realized fantasy land of Oz. This scene not only carries great significance for the plot as the beginning of Dorothy’s journey in Oz, but also holds deeper metatextual meaning through its use of visual language to create a spectacle for the audience. By applying the concepts of “the cinema of attractions” and cinema as utopia as they relate to Dorothy’s arrival into Oz, we can draw parallels between the otherworldly spectacle’s effect on Dorothy and its emotional effect on the film audience, which is important because the spectacle of the journey The Wizard of Oz presents has allowed it to become such an iconic film.

The Wizard of Oz’s first twenty minutes depict Dorothy’s life in the flat plains and sparse rickety shacks of Kansas. This opening sequence is monochromatically tinted in sepia, much like a faded photograph, emphasizing the rustic and mundane nature of Dorothy’s existence.

[11:10]

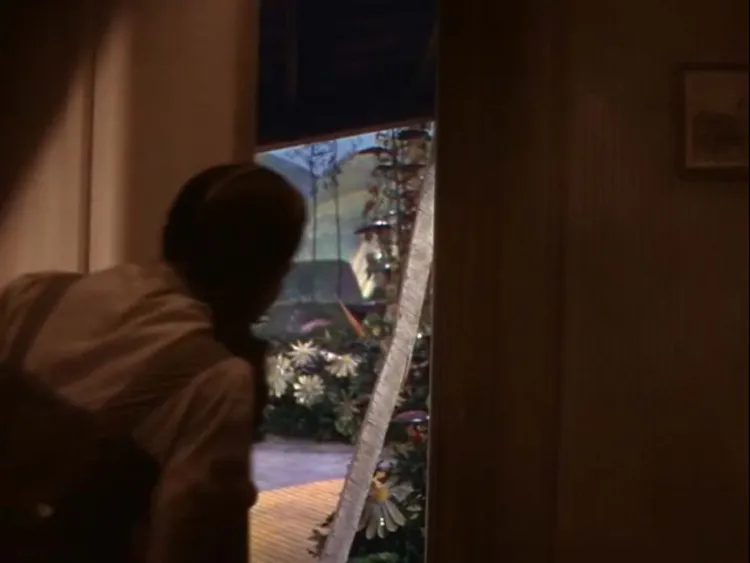

Then the twister whisks Dorothy and her house away, and upon landing, Dorothy (still in sepia) both literally and figuratively opens the door to a colorful world of wonder.

[19:31]

The colorization itself constitutes a spectacle: although color films had emerged at this time, splashing color onto a previously monochromatic world was a kind of wonder only possible through the medium of film. It’s important to note that the colorization is non-diegetic: Dorothy doesn’t see her own reality as black-and-white, but its absence of color is symbolic of the dreariness she finds in “reality”. The change to a colorized world is a visual spectacle conveying Dorothy’s sense of wonder to the audience, allowing it to better empathize with her, and signalling that the audience too is about to enter into another world that disregards the bounds of conventional reality.

As the camera pushes through the door frame, both Dorothy and the audience are dazzled by the scope of the Oz set: a green hilly landscape planted with giant flowers and covered in multiple tiers of whimsical dome-shaped architecture.

[20:35]

The camera cranes around revealing to the audience the colossal scope of the elaborate constructed sets. The viewers are able to share Dorothy’s amazement at the spectacle unfolding on screen and thereby experience the way Dorothy feels.

The film then cuts to a smaller spectacle: a medium shot of Dorothy, the audience’s first glimpse of the star in full color.

[19:45]

This not only makes Dorothy more human and therefore relatable but also signifies that Dorothy belongs as part of the colorful world of Oz. The spectacle continues as Dorothy meets the Good Witch Glinda and the crowds of colorfully clothed Munchkins greeting her with song and dance. The camera cranes upwards using wide, high angle shots to maximize the audience’s view of the sheer numbers of Munchkins and their highly choreographed performances, makeup, and costume design.

[29:05]

This framing of the Munchkin crowds, emphasizing their size and harmony, serves to further distinguish Oz from the sparsely populated depicted reality of Kansas. These visual marvels take the audience on a journey that parallels Dorothy’s journey through Oz.

In order to understand the reason for the cinematographic emphasis on the visual spectacle presented by Dorothy’s arrival into Oz, one must first understand “the cinema of attractions” defined by film scholar Tom Gunning as “cinema less as a way of telling stories than as a way of presenting a series of views to an audience, fascinating because of their illusory power [...] and exoticism” (Gunning, 57). According to Gunning, early days of cinema were dominated by non-narrative films eschewing plot coherence in favor of technical and aesthetic gimmicks that generated pure audience-thrilling spectacles designed to captivate audiences by allowing viewers to witness technical spectacles beyond their comprehension.

The importance of the spectacle supersedes The Wizard of Oz’s plot and demonstrates the power of the cinematic medium: a black-and-white reality giving way to an explosion of color and music, where constructed sets make fantasy a reality and color processes render vivid impressions. It exemplifies the arts that compose filmmaking– set design, costume design, choreography, cinematography, music – pushing them to the forefront of the audience’s focus. It is spectacle for the sake of spectacle, not strictly keeping with the cinema of attractions but following in its wake. As Gunning states, “The story simply provides a frame on which to string a demonstration of the magical possibilities of the cinema” (Gunning, 58).

For film scholar Richard Dyer, musical films and the spectacle they present represent a form of cinematic utopia or a representation of what utopia feels like, a chance for the viewers to momentarily escape their lives and imperfect society. Dyer defines utopia as an idealistic and imaginary solution to real social tensions, such as scarcity, exhaustion, and dreariness (see Dyer, 228). The utopian solutions to these problems include abundance, energy, and intensity (see Dyer, 228). According to Dyer, utopia is not concerned with systemic change or issues of race, class, and gender. Instead it presents an escapist solution, into a world where these problems either don’t exist or may be resolved in a simple and clean-cut manner.

Viewing Dorothy’s arrival into Oz through Dyer’s lens reveals the utopian aspects of Oz. In the real world of Kansas, Dorothy is surrounded by aesthetic signifiers of rural poverty. She lives on a barren farm where everyone dresses plainly (as fitting for lower-class laborers), and her friends are lower-class farmhands too busy with their monotonous tasks to bond with her. Dorothy is menaced by Miss Gulch, a higher-class woman who uses her higher status to bully others into submission. Kansas, and by extension the real world, can be described through scarcity, exhaustion, and dreariness, the kinds of real-world problems that fuel escapist desire, especially for an audience in the impoverished and unequal era of the Great Depression.

Indeed Dorothy, much like the audience, specifically longs for an escape from these mundane troubles. In the lead-up to her song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, itself a song celebrating a simple kind of escapism, Dorothy wistfully notes, “Some place where there isn’t any trouble ... It’s not a place you can get to by a boat or a train. It’s far, far away,” directly echoing Dyer’s statement that “Entertainment offers the image of ‘something better’ to escape into, or something we want deeply that our day-to-day lives don’t provide” (Dyer, 222).

Dorothy gets her wish, finding herself in the colorful Munchkinland, which presents simple and utopian solutions to the problems in the real world. None of the Munchkins seems wealthier than the others– they all live in the same kinds of fancy houses and wear colorful high-class attire. The occupations are communicated through song and dance and include such childlike concepts as tulips and lollipops, making work and play seem synonymous. The singing and dancing are full of excitement, both for the Munchkins themselves as well as the audience watching the spectacle. The Munchkins are harmonious in their play, and when trouble appears, the fantasy tyranny of the Wicked Witch of the West is more defeatable than the class struggle represented by Miss Gulch.

Munchkinland, and by extension Oz, is cinematic utopia, both in its harmonious nature and in its disinterest in real-world solutions. This is in no way an accident. The official Photoplay guide states, “The setting of the story is in that Never-never Land to which we sometimes wish we might go to escape from the ills that plague us or to get away from the ordinariness that besets our humdrum lives– that beautiful and terrible land from which in the end we are glad to return home” (Photoplay, 3). This description matches the sentiments that Dyer links to the audience’s desire for utopia, and in this manner, Dorothy’s journey into Oz mirrors the audience’s own journey watching The Wizard of Oz.

Mirroring the land of Oz’s effect on Dorothy, The Wizard of Oz transports its viewers into an idealistic world that brings their fantasies to life. It presents a grand spectacle (both within the world of the film and the nature of its production) and a vision of utopia that entrances its audience because of its separation from the real world. It is in tune with the primal desire for escape from mundanity and realizes the solution in a truly spectacular manner. Dorothy opens the door for the audience into this world where the unreal is made real. And like Dorothy, once the journey is over, they return home.

Bibliography

Dyer, Richard. “Entertainment and Utopia.” Movies and Methods, vol. 2, 8 July 2005, pp. 220–232, doi:10.4324/9780203993941.

Gunning, Tom. “The Cinema of Attractions Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde.” Early Cinema: Frame, Space, Narrative, 1990, pp. 56–62, doi:10.5040/9781838710170.0008.

https://archive.org/details/photoplaystudies561nati/page/n161/mode/2up?…