Histories in the Shadows: Cinematic Resistance in Taiwanese and Hong Kong New Wave

Essay by Kiki Hu '28 for Chinese & Sinophone Cinemas Course

As Chinese and Sinophone cinema flourished during the ‘new wave’ from the 1980s, film became a powerful medium for engaging with history. A new focus on social and historical realities emerged, prompting questions about whether and how these films should be interpreted through a historical lens, especially when they deliberately avoid direct representation of historical events. This essay argues that A City of Sadness (1989) and Made in Hong Kong (1997), through their distinct camera styles and focus on the lives of marginalized individuals, act as cinematic resistances to official historiography. By capturing emotional undercurrents and social dislocation through formal opacity, these films challenge dominant narratives and participate in the construction of historical meaning, thus delivering a form of justice to history through mood, style, and perspective.

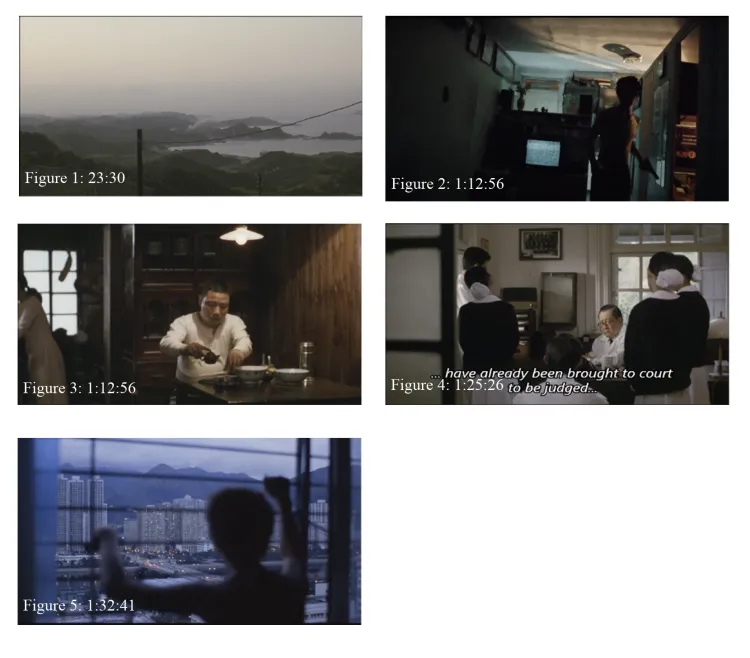

Firstly, distinct in their own styles, both films employ an opaque approach that helps to re-create the nuanced and complicated mood of their respective historical moments. A City of Sadness is marked by Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s auteuristic use of static and extreme long takes. Among them, one notable feature that contributed to the film’s meditative tone is his use of empty shots. This is best illustrated by the scenic shot of low-lying hills (Figure 1). The shot, which frames a serene landscape stretching to the horizon with only power lines in the foreground, lingers for 37 seconds without any camera movement. Unlike an establishing shot or a cutaway, this long take is especially unusual, standing on its own as a “prolonged” and “unmotivated” absence (Duan 2021). For the entire duration of the shot, there is no human subject and no narrative information conveyed, making this shot seem almost superfluous, devoid of any “apparent intention” (Duan 2021). These specific techniques all come together and contribute to associative editing that renders this observational, documentary-like style that allows the audience to detach from the subjective viewpoint and evoke emotions beyond the diegetic world. Taking on the emotion of the previous scene, where people are discussing changing the Japanese flag into Chinese flag after Japan relinquished Taiwan, people both express a sense of belonging and hold mixed feelings towards the Nationalist party. Here, the associative editing smooths the unresolved emotions into the empty shot, which becomes a vessel for the undercurrents of sentiment surrounding Taiwanese national identity to simmer. Amidst such a monumental transformation, people are left not with simple relief or joy but with feelings of dislocation, nostalgia, uncertainty, and disillusionment. They struggle to find a sense of belonging, feeling alienated and oppressed by the twin forces of Japanese colonization and Nationalist rule. Hou’s stylistic choices help brew a quiet, haunting sadness that embodies the inexpressible emotional currents of the time.

While stylistically opposed, Made in Hong Kong similarly crystallizes emotional turmoil —this time through dynamic and chaotic form. Chan frequently employs hand-held cameras to produce bold and fluid camerawork that mirrors the instability of the characters’ lives, effectively exemplified in the shot of Moon dancing before the assassination (Figure 2). In this sequence, Moon rushes from the far right of the frame to the foreground, eventually filling the entire frame. The camera swings under his armpit, showing an extreme close-up of Moon holding a gun in his flailing arms as he dances aimlessly. Here, nothing is in focus, and the audience is left with an ambiguous silhouette of Moon. Understanding this sequence within the larger narrative, we know Moon is preparing for an assassination. But instead of deliberate, organized movement, both his actions and the camera work are outright chaotic. In this intense and claustrophobic atmosphere, the juxtaposition of a gun—representing violence—and his dance—typically associated with joy—creates a trippy, jarring effect. This tension reflects his deep emotional disarray, as he tries to numb and lose himself in a moment of spontaneous physicality, masquerading his fear of having to execute the murder. This distorted, fragmented psychological state is not just Moon’s; it also reflects a broader public disorientation where people feel lost, alienated, vulnerable, and abandoned by both the colonial past and the uncertain future under new rule. The golden age of economic prosperity and strong longing of reunion never belonged to them; those living on the margins were hopelessly left behind by the fast-moving world, trapped in a meaningless survival quest steeped in violence and confusion. Despite their stylistic divergence, both Hou and Chan capture alienation and dislocation, articulating the emotional turbulence of their historical moment.

Secondly, both films focus on common people during periods of significant social change, offering often neglected voices a rewrite to the grand and hegemonic historiography. In A City of Sadness, the film centers on the experiences of a single family that holds little significance within the larger national events. The protagonist, Wen-Chiang, is a deaf-mute, a group rarely represented in cinema. Moreover, the film frequently emphasizes the domestic, interior lives of the characters, such as in an extended long take where Wen-heung rinses his tea ware for over four minutes (Figure 3). Without building up to any dramatic tension, this shot presents an uninterrupted and realistic view of daily life. The use of deep focus invites the audience to engage actively with the frame, democratizing their attention by encouraging them to notice details indiscriminately. In another instance, during the announcement of martial law, a moment thought to mark the climax of brutality, Chen Yi’s voice is only heard over the radio, while the camera stays on the doctors and nurses in the hospital (Figure 4). Rather than centering on historically significant figures, Hou refuses to trivialize events of people’s life, portraying history not as a thread of “big events” but as something equally experienced by all. It is Hou’s special focus on the ordinary that resists the government’s grand narrative of history, which blames the February 28th Incident on communists riots, exposing another side of history by focusing on the personal and the subtle.

In a similar vein, Made in Hong Kong focuses on the most inconspicuous figures in the fabric of society. Moon, a high school drop-out, steals, fights, drifts aimlessly through life, and holds no place of social importance. While the film may appear to be a coming-of-age narrative, it reveals deeper anxieties about the dislocation and alienation of Hong Kong’s marginalized youth amid the velocity of change in Hong Kong. This is highlighted by the sequence when Moon calls Ms. Lee during her wedding and confesses he feels “truly worthless” for failing to protect his friends, Ping and Sylvester (Figure 5). The camera then shifts the focus from Moon to the glowing high-rise buildings outside the window, with Moon blurred in the foreground. This juxtaposition creates a contrast between the prosperous city and the helpless, despairing, and bleak silhouette of Moon. The window bars, symbolizing a prison, seems to trap him in a cramped cell that marks both the figurative and physical distance from him being able to respond to the changing world that elude his comprehension. In a few short decades, Hong Kong transformed into a global financial center, and the approaching 1997 handover was seen as a symbol of progress and reunification with China. Yet, this teleological narrative, which emphasizes progress and prosperity, leaves no room for those like Moon who cannot fit into the harmonious but dominant discourse of modernization. Through Chan’s portrayal of Moon, the film gives voice to the disaffected youth living at the bottom of society, destabilizing Hong Kong as a symbol of modernity and prosperity and therefore offers a counter-narrative that exposes the existential crises faced by the marginalized. Though the Lin family is more socially secure than Moon, both represent ‘small figures’ caught in the margins of historical transformation. Their amplified voices destabilize dominant historiography and assert the political weight of the everyday.

As neither film explicitly speak to the historical events, evading dramatic and massive scenes of direct representation, questions have always lingered about how these films should be interpreted. Is a historical reading necessary? And if so, does their elliptical, opaque approach do justice to history? Fredric Jameson, in an absolutist understanding, argues that all third-World texts “necessarily project a political dimension in the form of national allegory” (1986, 69). Others, like Aijaz Ahmad, argue against such a generalization, seeing it as undermining the individuality and complexity of these texts and diminishing the cultural specificities of each work (1987, 122). Despite this debate, the very fact that these stories unfold against such a historical backdrop makes it impossible to escape a historical reading, as the characters, events, and themes are themselves reactions to, responses to, and products of the historical narrative from which they are inextricably born. As we assess these films through the lens of history, interrogating a justice behind their presence as historical representation exposes an inherent ambivalence in the understanding of history. As Michel-Rolph Trouillot suggests, history involves a dual participation as both “what happened” and what is “said to have happened” (1995, 2). Meanwhile, there is an irreducible overlap between the “what happened” and what is “said to have happened.” The justice of historical representation, then, does not rely on factual accuracy alone. Even documentaries, with their aim for factual precision, are still directed and organized to create designated organization, structure, and perspective with specific focuses. Simply put, there’s no truth without mediation. In this sense, justice delivered by these films actually lies in the process of reproducing and re-presenting the past from a present standpoint of actively engaging with historicity itself. Criticism of these films for ‘political ambiguity’ or ‘historical inaccuracy’ reveals less about the films themselves than about our own assumptions about how history should be represented. This requires us to acknowledge that historical representation is, in itself, historical. Thus, a reading of films like A City of Sadness and Made in Hong Kong through a historical lens is necessary. To reduce these films to national allegories not only overlooks cultural specificity but also ignores how the act of representing the past onscreen shapes our very understanding of history itself. Therefore, as these films engage with the ongoing negotiation of meaning, they preserve justice and truth in participating in historicity.

In conclusion, A City of Sadness and Made in Hong Kong engage with history not through grand reconstructions but through a quiet resistance—through mood, form, and marginal perspective. Their stylistic opacity allows for emotional resonance where words might fail, and their focus on overlooked lives challenges who gets to be remembered. In refusing direct representation, they invite viewers to reflect on the very act of remembering. Justice, then, lies not in reproducing history faithfully, but in opening space for voices that history tried to forget.

Works Cited

Ahmad, Aijaz. “Jameson’s Rhetoric of Otherness and the ‘National Allegory.’” Social Text No.17 (Autumn 1987): 3-25.

Chan, Fruit, dir. 1997. Made in Hong Kong.

Duan, Siying. 2021. “Thinking, Feeling and Experiencing the ‘Empty Shot’ in Cinema.” Film-Philosophy 25 (3): 346–61. https://doi.org/10.3366/film.2021.0179.

Hou, Hsiao-hsien, dir. 1989. A City of Sadness.

Jameson, Fredric. 1986. “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism.” Social Text, no. 15: 65–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/466493.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press.

Appendix