In Honor of Nobel Laureate David Baltimore ’60, H’76

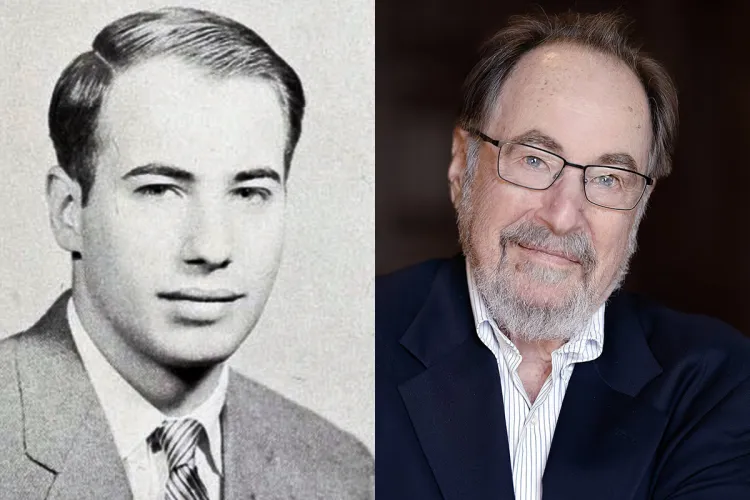

David Baltimore '60, H’76 from the 1960 Halcyon and in 2021.

Nobel laureate David Baltimore '60, H’76, a towering and influential figure in the field of microbiology and an advocate of liberal arts education, died Saturday, Sept. 6, after a long illness. He was 87.

Baltimore shared the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Howard Temin '55 and their colleague and former teacher, virologist Renato Dulbecco, for their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumor viruses and the genetic material of the cell. In 1970, Baltimore and Temin, working separately, discovered an enzyme, reverse transcriptase, that is essential for the reproduction of retroviruses such as HIV. [More on their discovery below.]

After earning a B.A. with High Honors in chemistry, Baltimore received a Ph.D. from Rockefeller University, where his thesis on establishing ways to study viruses in animal cells was considered a major breakthrough. He later served as president at Rockefeller as well as the California Institute of Technology.

An early advocate of AIDS research, Baltimore had a profound influence on national science policy, spanning everything from stem cell research to cloning. He was a past president of the American Association of the Advancement of Science, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Baltimore, the author of approximately 680 peer-reviewed articles, focused his later work on the control of inflammatory and immune responses, the roles of microRNAs in the immune system, and the use of gene therapy methods to treat HIV and cancer. He was awarded the National Medal of Science for his prodigious contributions to science in 1999.

At Swarthmore

Baltimore first studied biology at Swarthmore, then switched to chemistry in order to pursue his own research. The summer before his senior year, he encountered the then-burgeoning field of molecular biology for the first time at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. Upon his return to campus, he found fellow students who also wanted to delve further into the field and led weekly seminars on the subject, inviting to campus a number of leading experts.

Baltimore, who served as vice chair of the Board of Managers from 1986 to 1989, returned frequently to speak on campus, especially to discuss why scientists need a liberal arts education.

“In spite of the great satisfaction in science and the frustration of attempting to affect social attitudes, I still believe that a complete life requires both activities,” he said when addressing the Class of 1976. “It is the essence of a liberal arts education to instill beliefs in both right and truth.”

When Baltimore gave the keynote address at the opening of the Science Center in 2005, he called on American higher education to turn out more graduates trained in science and engineering and commended his alma mater for its leadership in science education: “The focus on laboratory science represented by this building is so vital to Swarthmore continuing to serve the critical educational role in the sciences that it has served for so long." Most recently, he joined a panel discussion on science in the U.S. during Alumni Weekend last year.

“It is the essence of a liberal arts education to instill beliefs in both right and truth.”

In 2007, the David Baltimore/Broad Foundation Endowment was established by a grant from the Broad Foundation at his request. The fellowship is awarded to a Swarthmore student doing summer research in the natural sciences or engineering, with a preference given to a student engaging in mentored off-campus laboratory research — experiences he enjoyed himself and credited with fueling his own passion for a life devoted to science. Baltimore’s name also appears on a plaque in a Singer Hall seminar room, having moved from its original home in Martin Hall.

Reflecting once on his time at the College, Baltimore said: “I guess the thing I’ll always remember best about Swarthmore is the marvelous time we all had, while we were getting a handle on the things we were going to do in life.”

Reversing the Central Dogma in Molecular Biology

In 1970, Baltimore and Temin, working separately, discovered an enzyme, reverse transcriptase, which appeared to challenge the central dogma of Francis Crick and James Watson. Crick and Watson had famously received the Nobel Prize in 1962 for determining the double helical structure of the DNA molecule and recognizing the possibilities of that configuration as an appropriate storehouse of genetic information.

Temin’s hypothesis, that the RNA of RNA viruses could modify the host cell’s DNA, changing its encoded genetic information, was not generally accepted until he and Baltimore demonstrated reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that mediates the reaction. In Temin’s case, the tumor viruses were Rous sarcoma viruses causing tumors in chickens. Baltimore used viruses causing tumors in mice.

Temin and Baltimore — who had actually met years earlier when Baltimore was in high school and they both spent a summer at Jackson Laboratory, a biomedical research institute in Maine — simultaneously published their results in the journal Nature. Dulbecco developed the laboratory techniques they used to study the molecular biology of animal viruses, though he didn’t participate in the work.

As Baltimore once described the Nobel experience in the Bulletin, it was “like being in a Fellini movie — as one of the characters!”