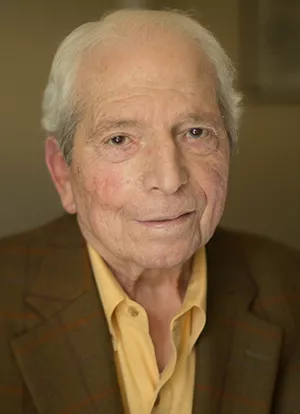

In Honor of Longtime English Literature Professor Harold Pagliaro

President Valerie Smith shared the following message with the campus community on Feb. 19, 2020:

Dear Friends,

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Provost Emeritus and Alexander Griswold Cummins Professor Emeritus of English Literature Harold E. Pagliaro died peacefully on Saturday at his home in Swarthmore, where he had lived for more than 50 years. He was 94.

Harry devoted his academic and professional life to teaching and writing about literature and poetry after experiencing the horror of combat during World War II. A respected figure on campus well after he retired, Harry taught and led with great wisdom and vision.

Harry is survived by his wife, Judith; their children Robert, Susanna, and John ’93, and a son Blake from a previous marriage; five grandchildren; and one great-grandchild. Details about a campus memorial service later this spring will be shared when they are available.

I invite you to read more below about Harry, his remarkable life, and his innumerable contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Valerie Smith

President

In Honor of Harold E. Pagliaro

The Swarthmore community has lost one of its most respected and stalwart members, Provost Emeritus and Alexander Griswold Cummins Professor Emeritus of English Literature Harold E. Pagliaro, a renowned scholar of 18th-century English literature and a guide and mentor to generations of students and colleagues. Pagliaro died Saturday, Feb. 15, at age 94.

“Familiar with the entire canon of Western literature, Harry seemed to me to embody the virtues associated with the humanities themselves,” says Philip Weinstein, the Alexander Griswold Cummins Professor Emeritus of English Literature. “Intensely intellectual, fiercely alert, a productive scholar of Romanticism as well as a loyal defender of Swarthmore College, Harry contributed immeasurably to this place.”

“Harry’s passion for his subject spilled over onto inked remarks in the margins of critical books in the library, as if his seminar teaching could not be constrained to the time and space of a classroom,” says Professor and Chair of English Literature Betsy Bolton. “A memoirist and poet as well as a scholar, Harry remained dedicated to literary arts in his retirement as well as his teaching career.”

Pagliaro was born and raised in the Bronx, N.Y., but graduated from high school in Portsmouth Va., where his family had relocated temporarily due to his father’s work as an engineer. When he returned home to New York, Pagliaro enrolled at Columbia College and studied engineering at his father’s urging. After two semesters, at 18, he was drafted into the Army during World War II.

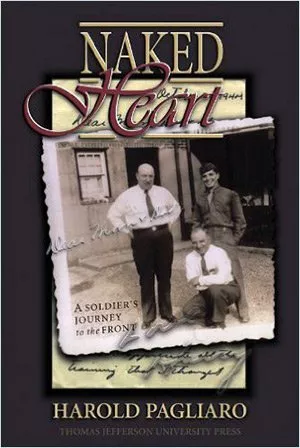

Pagliaro's book Naked Heart: A Soldier’s Journey to the Front (1996) is one of the few World War II memoirs written from a private’s point of view.

Trained for the infantry at Fort Benning, Ga., Pagliaro was taken from his division and sent directly to the European front as a solo replacement. Pagliaro survived near-constant danger and severe injuries, ultimately receiving a Purple Heart, a Combat Infantry Badge, and a Bronze Star.

“Harry has reflected eloquently on how his experiences in combat during World War II haunted him for the rest of his life,” says Peter Schmidt, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of English Literature. “Yet the horror of war inspired him all the more intensely to love life and fight for the values expressed by Swarthmore’s liberal arts education.”

After being discharged from the Army in 1945, Pagliaro resumed classes, in literature this time, at Columbia, where he ultimately earned a bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. He taught Greek and Latin literature in translation there before joining Swarthmore’s faculty in fall 1964.

When the newest members of the faculty were announced in The Phoenix that spring, Pagliaro’s hiring was reported as a “steal,” such that the Columbia Daily Spectator “bemoaned the loss of their dynamic English mentor.” Noting how his “fine reputation” had preceded him, The Phoenix also stated that, before he had even arrived on campus, nearly 50 students had enrolled in his 19th-century poetry class.

Of teaching, Pagliaro said, “I wanted to give a real shape to my life — to commit myself to a profession that would quicken the best part of me in useful work.”

At Swarthmore, Pagliaro taught courses in 18th-century English literature and English romantic poetry. Among his publications are a book on English writer and artist William Blake, Selfhood and Redemption in Blake’s Songs (1987), many articles, and two critical editions, The Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon (1963) and Major English Writers of the Eighteenth Century (1969).

In 1970, Pagliaro became a full professor and chaired the English Literature Department until 1974, then again from 1986 to 1991. He also served as chair of the Humanities Division. In 1974, he was named the College’s second provost and served in that role, under President Theodore Friend, until 1979. A former wrestler, he also found time to serve as faculty adviser to the wrestling team.

A charter member of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Pagliaro was its annual-proceedings editor for three years. He was also a member of Columbia’s seminar on Eighteenth-Century European Culture, and had been a senior fellow of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

After 28 years of teaching at Swarthmore, Pagliaro retired in 1992. Upon finding a cache of letters he had written to his parents while stationed away from home, Pagliaro set out to document his war experiences. His book Naked Heart: A Soldier’s Journey to the Front (1996) is one of the few World War II memoirs written from a private’s point of view.

In clear, direct prose, Pagilaro described fighting as a 19-year-old alongside veteran combat soldiers with whom he had never trained or served. Although he was put at extreme risk in a series of patrols and attacks, he was never told anything about the missions — not the names of places, the likely strength of the enemy, nor the strategic value of the objective. That systematic withholding of information added to his anxiety and fear. His exposure to danger and loneliness finally ended when German shell fragments tore apart his lower leg, delivering him permanently from the front to a long recuperation.

More than 50 years after his service, Pagliaro still suffered nightmares.

“The dreams are always the same,” he said when Naked Heart was published. “I’m being sent back to the front, about to be exposed to death again, and again I’m under somebody else’s control, an officer or noncom[missioned officer]. I don’t own my own body. And I’m kept ignorant of what I’m doing. Writing the book was an attempt to externalize the material of the dreams. But it didn’t work. I still have the nightmares, one as recently as last week.”

Despite his harrowing experiences, Pagliaro said his combat service did not leave him bitter.

“If anything, it left me cherishing life all the more, maybe because I realized that I might have lost it then,” he said. “I would not give up the experience of war even if I could. But I would kill or die before letting anybody force me to repeat it.”

During retirement, Pagliaro continued to feed his intellectual curiosity and worked regularly in his campus office. His work from that time included Henry Fielding: A Literary Life (1998) and Relations Between the Sexes in the Plays of George Bernard Shaw (2004). He also wrote and published sonnets.

Colleague Craig Williamson, the Alfred H. and Peggi Bloom Professor of English Literature, says Pagliaro had a way of conceiving and understanding poems and problems that was both imaginative and compelling.

“In this respect he was like the poet he so admired and wrote about, William Blake, who once said, ‘He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star,’” Williamson says. “Harry was a light-bringer to all of us, and his words and ideas in his books and in our memories will continue to shine.”

As a department chair, Pagliaro led numerous faculty searches. In describing what he looked for in candidates, he also easily could have been describing himself: Does the person have “an original and responsive mind?” The “capacity for energizing the minds around them?” Are they “likely to engage students?” He noted Swarthmore’s justifiable reputation as a “very intelligent and very alive” community.

“Bright and alive,” said Pagliaro. “That is just the long and the short of it.”