In Honor of Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Asmarom Legesse

President Valerie Smith shared the following message with the campus community on February 13, 2026:

Dear Friends,

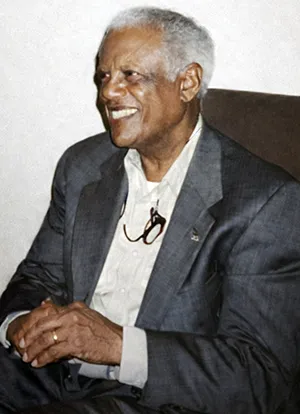

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Asmarom Legesse died in Philadelphia on Jan. 31, just a few days shy of his 95th birthday.

Asmarom, who served on the faculty for 20 years, is remembered as much for his brilliant and courageous scholarship as for his significant contributions to the Swarthmore community during particularly challenging times on campus in the 1960s and 1980s. To those from his homeland of Eritrea, whose hardships and achievements he documented, he is an inspiration.

Asmarom is survived by his wife, Bisrat (Guoy) Marikos; daughters Sarah and Elizabeth; son-in-law, Ermias Michael; and siblings Isaac Zere, Bisrat Zere, Letebrhan Legesse, and Kassahun Legesse. A memorial took place at the Rehoboth Afaan Oromo Christian Church in Ridley Park on Saturday, Feb. 7.

I invite you to read more below about Asmarom and his lasting impact on our community and beyond.

Sincerely,

Valerie Smith

Swarthmore College President

Roy J. and Linda G. Shanker Presidential Chair

In Honor of Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Asmarom Legesse

Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Asmarom Legesse died Saturday, Jan. 31, at 94. With his passing, Swarthmore has lost a pioneering and influential scholar and mentor who provided early critical support for Swarthmore’s Black Studies Program and for the College’s divestment from businesses operating in apartheid-era South Africa. Eritrean by birth, African by commitment, and global by scholarship, he warned against his field’s history as an instrument of colonization and worked to rethink it to prevent further damage.

“Asmarom Legesse was a brilliant anthropologist and a treasured colleague in the Department of Sociology & Anthropology,” says Centennial Professor Emerita of Anthropology and Provost Emerita Jennie Keith. “His research among the Oromo of Kenya and Ethiopia led to classic publications about Indigenous African democracy. Multilingual and very cosmopolitan, he excelled in a wide range of interests and skills. He really was an amazing person.”

“Asmarom was a very good friend, indeed,” says Centennial Professor Emeritus of Sociology Braulio Muñoz. “By the time I got here, he was already known as a soft-spoken but decisive advocate on behalf of minority faculty and students. The man was not only a first-rate scholar but also a wonderful human being.”

“Working with Asmarom was always productive, always a pleasure,” says Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Steve Piker. “He was an eclectically creative and brilliant anthropologist, and unfailingly conveyed warm and sincere appreciation for whomever he was with. And his smile! He seemed always to wear it, and one didn’t so much see it as feel it.”

Legesse was born in 1931 in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea when it was an Italian colony, and began his formal education at the Swedish Evangelical Mission School. There, he developed a lifelong love for music. Encouraged by his family, he learned to play the violin and piano, later attending the government-operated Italian School in Asmara.

After graduating from Teferi Mekonnen School in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Legesse studied medicine as an undergraduate at Makerere University in Uganda. After two years, he was expelled for opposing the colonial curriculum, which excluded law and political science. At another point in Legesse’s undergraduate career, the president of his university closed the school after a student demonstration, expelled all students, and then invited back only some, Legesse among them.

Legesse ultimately earned a B.A. in education from the University College of Addis Ababa and, determined to continue graduate study, came to the U.S. on a scholarship to Harvard University. After completing an Ed.M. in 1957, he pursued a Ph.D. and conducted field research back in East Africa with support from the National Science Foundation.

Legesse joined Swarthmore’s faculty in Fall 1968. A few months later, and as the College’s only Black faculty member, he found himself in a unique position during the Admissions Office sit-in by Black students, who were pushing the College to address several concerns. Having agreed to serve as the faculty-student liaison, he talked with the students often late into the night and with the faculty during the day, negotiating between the two groups.

After the sit-in concluded, and in a rare show of public support for the students when interest in their concerns seemed to wane, Legesse wrote an open letter to the faculty, stating: “If the grievances of a few Black students at Swarthmore were valid enough to claim our undivided attention last week, they are no less valid today.”

Work to address the students’ concerns soon got underway. Legesse supported these efforts, serving as a faculty representative on a group to increase Black student enrollment, teaching courses in Black Studies, helping to hire the first Black Cultural Center director, and later serving as a coordinator of the Black Studies program.

Reflecting 20 years later in The Phoenix, he acknowledged that some of his colleagues had disapproved of the students’ actions, if not their goals. Still, he thought the events as they occurred were necessary: “A great deal was achieved in those two weeks, something that would have taken an entire decade to accomplish without it.”

“Asmarom contributed vitally to the College negotiating that difficult period as successfully as it did,” Piker says. “And, of course, to know Asmarom is to love him. In the boiling cauldron of the late ’60s and early ’70s, that didn’t hurt one little bit.”

The experience affected Legesse as well. “In a way my mind was shaped in the throes of the Civil Rights Movement,” he said. “All of that [became] part of my thinking.”

In 1971, Legesse completed his Ph.D. at Harvard and left Swarthmore to hold teaching positions at Boston University, The Hague, and Northwestern University. He also published his seminal Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society (Free Press-Macmillan, 1973), in which he examined the political, economic, and social system of the Oromo people of Ethiopia. This and Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System (Red Sea Press, 2000) remain authoritative texts on Indigenous governance and collective leadership.

“[Legesse] was an eclectically creative and brilliant anthropologist, and unfailingly conveyed warm and sincere appreciation for whomever he was with," says Steve Piker. "And his smile! He seemed always to wear it, and one didn’t so much see it as feel it.”

Legesse did more than bring the centuries-old tradition to a global audience. He demonstrated the value of Indigenous knowledge, insisting that African systems be understood through their own terms, not by those shaped by colonial lenses. This is most powerfully articulated in Gada’s concluding essay, which so unsettled the anthropology community that the University of Chicago Press would only publish the book without it. Legesse changed publishers.

For his ethnographic study, Legesse spent the better part of two years living and participating in the daily life of Oromo society, which he described as a personally satisfying experience. Through studying another people, he said, “one learns ways of validating one’s culture [and] background. The whole question of cultural identity is a crucial one for modern Africans.”

Not long after, an experience while on sabbatical in Addis Ababa completely altered Legesse’s academic career. While doing field research in the city, he heard about a possible famine north in Eritrea. Although the government did not admit to it, he decided to check out the rumor and took off in his Land Rover.

“I did indeed find a devastating famine,” he told The Phoenix. “After I returned to Addis Ababa, I wrote a paper documenting what I had seen, and it was distributed underground.” He also helped to make a documentary film that circulated in Europe, which he said caused a furor because Ethiopia’s then-emperor continued to insist there was no famine.

“From that time on, I abandoned my concern with grand and intellectually sophisticated theoretical matters,” he said, “and began delving into the kind of anthropology that is intended to make a difference in human lives.”

The next year, the Ethiopian monarchy was overthrown and replaced with a Marxist-Leninist military government. The development, Legesse said, “deeply estranged most Ethiopian and Eritrean intellectuals like me and drove us deeper into exile.”

In 1976, Legesse rejoined Swarthmore’s faculty. “We were delighted that he wanted to return,” Piker says.

Back on campus, Legesse again found himself in a position to exert influence. During the campaign against South Africa’s apartheid government, he urged community members to write to the College’s Committee for Ethical Investment Recommendations and advocate for total divestment. As a faculty member on the committee, he helped the group reach consensus in supporting that position, which the College adopted in 1986.

But Eritrea’s future remained a concern. During a research trip in 1984, he visited areas under the control of the Eritrean Relief Association (ERA), which were continually exposed to bombardment by the Ethiopian air force.

“For the first time in my life, I learned to distinguish Soviet MiGs from friendly aircraft and to run for cover whenever MiGs flew overhead,” he said.

Despite the danger and impressed by the dedication of those he saw working for independence, Legesse pivoted his work to more fully support the liberation movement. He returned again in 1988 and visited refugee camps, conducting lectures on survey methodology, photography, and how to digitize and preserve data. From Swarthmore, he also served for nine years as chair of the ERA in the U.S., balancing his campus responsibilities with traveling and speaking around the country to raise funds for food, medicine, and other supplies.

Indeed, according to Keith, “Asmarom was a pioneer in the use of computer simulation to understand the complexities of traditional social and political organization in Africa.” He was also a skilled woodworker, and once married the two seemingly disparate interests by constructing a desk shaped like a miniature pianoforte whose cover opened like a piano lid to reveal the computer within.

Soon after formal independence from Ethiopia was declared in 1993, Legesse retired from the College and returned to Eritrea. There, he served as academic vice president of the University of Asmara for a year and as a research advisor to the government with special responsibilities in several ministries. He also held consultancies with UNICEF, the United Nations Development Program and World Food Program, and agencies in Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom. He returned to campus in 1995 as the visiting Cornell professor and taught courses informed by his research on food security and dislocated societies.

Legesse also continued his advocacy and research. At the beginning of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War in 1998, he published The Uprooted, a series of reports on behalf of Citizens of Peace in Eritrea concerning human rights violations of ethnic Eritrean deportees from Ethiopia. In documenting testimonies from thousands of victims, he decried the social and economic situation created by “the escalating flow of deportees sent across the border without due process of law, often under cruel and inhuman conditions.”

Legesse returned to Philadelphia in 2012. In 2016, UNESCO added the Gada political system to the list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity, with Legesse’s work cited among its principal references. He also received an honorary doctorate from Addis Ababa University.

And he continued speaking and writing. In 2019, Legesse published a second edition of Gadaa: Democratic Institutions of the Boorana-Oromo, ending with a new chapter on the future of Oromo democracy that he proposed could be applied to the modern world.

Throughout his career, Legesse approached his scholarship not only as an academic exercise but a moral obligation. In the 1973 essay that necessitated him changing publishers, Legesse noted that Africans who wish to learn about their cultures find themselves in a peculiar position: They must rely on sources written by Westerners on the basis of data largely gathered by European scholars for the benefit of their own societies.

Not surprisingly, he said, the literature rarely addressed itself to African concerns. Moreover, the analytical procedures developed by social scientists were “products of specific cultures and tend[ed] to be associated with particular cultural presuppositions” — and that “by far the most pernicious and pervasive” was the belief that “Western culture is superior” to all others.

Directing his personal statement to the African audience he described as his source of inspiration, he said: “Our defense is twofold: We can either address ourselves to it with effective counterpropaganda, or attempt to expose its weaknesses with the aid of science. Both strategies are necessary. I prefer to follow the latter course of action.”