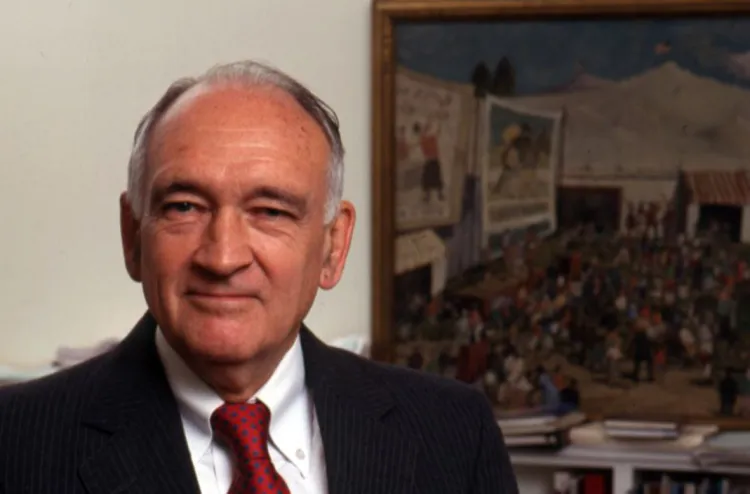

In Honor of Emeritus Manager, Retired Vice President William Spock ’51

President Valerie Smith shared the following message with the campus community on November 20, 2025:

Dear Friends,

I write with the sad news that emeritus manager and retired vice president for business and finance William Thomas Spock ’51 died on Saturday, Nov. 1. He was 96.

Bill had a long and successful business career before joining the Board of Managers and then serving as a member of the College’s senior staff. He is remembered as much for his financial acumen and wise stewardship as for his mentorship and self-effacing manner, providing a model of leadership that friends and colleagues alike still seek to emulate.

Bill is survived by Patricia, his wife of 66 years, who worked for several years at ABC Strath Haven House; four children, including current Manager Tom ’78, and their spouses; five grandchildren with two spouses; four great-grandchildren; and his sister Elizabeth Newgeon and her family.

A family memorial will take place next summer. In lieu of flowers, the family welcomes donations to the William T. ’51 and Patricia E. Spock Scholarship, which is awarded with preference to a student majoring in mathematics or the fine arts.

I invite you to read more below about Bill and his many lasting contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Val Smith

President

In Honor of Emeritus Manager, Retired Vice President William Spock ’51

Emeritus Manager and retired vice president for business and finance William Thomas Spock ’51 died on Saturday, Nov. 1, at 96. With his passing, the Swarthmore community has lost one of its most admired, influential, and generous leaders.

"During his tenure, Bill strengthened the functioning of the College through astute hiring, improved administrative practices, the construction of important facilities, and the diversification of the College’s endowment, leading to lasting benefits to our community," says Chair of the Board of Managers Koof Kalkstein ’78. "He was also warm and caring, reflecting the melding of a capable business mind with a Quaker spirit."

“Bill was a tremendously wise while warm and gentle leader,” says Claire Sawyers, whom Spock hired to lead the Scott Arboretum and who recently retired after 35 years in that role. “I feel he ‘walked the talk,’ living and demonstrating the foundational values of the College. I'm blessed that my life intersected with his the way it did.”

“Bill lived his life making a place for people, not putting people in their place,” says Stu Hain, retired vice president for facilities and capital planning, and also a Spock hire. “I see him as the epitome of Swarthmorean caring, and his example as a gentleman and a leader is a lighted marker for me.”

Spock was born in New York City in 1929 and raised in Leonia, N.J., where he attended high school and was the valedictorian of his graduating class. Spock arrived at Swarthmore in 1947, all of 5’6” and 130 pounds. But he quickly established himself as a three-sport varsity athlete, known for leadoff line drives for the baseball team, soccer goals, and as a guard on the men’s basketball team. Spock was considered the sparkplug of his squads and, according to the Halcyon, a true “team man and pressure player.”

These qualities were celebrated his senior year, when Spock received the first Kwink Trophy. Awarded every year since by Athletics, it recognizes a senior who best exemplifies service, spirit, scholarship, society, and sportsmanship.

Spock, as seen in the Halcyon, graduated with Honors in mathematics and physics.

Spock’s prowess also extended to the classroom, and he was good-naturedly remembered in the Halcyon as a “sawed-off mental giant,” for his “keen analytic mind,” and for how his “taciturnity complement[ed a] sudden emergence of trenchant wit.” He graduated with Honors in mathematics and physics and was elected to Sigma Xi, the scientific honor society. At Commencement, he also received the Ivy Award, given to the outstanding man in the graduating class.

In 1952, Spock was drafted by the U.S. Army, and he served during the Korean War in the 3rd Infantry Division. For his service providing photo interpretation behind the lines, he received commendations and was promoted to Sergeant First Class. When he returned in 1953, he joined Penn Mutual Life Insurance Co. in Philadelphia as an actuarial trainee and associate.

That year, Spock also married his fiancée and fellow scholar-athlete Elizabeth “Betty” Daugherty ’52, a cheerleader and women’s basketball player from Elkins Park, Pa., who had graduated with Honors in English literature. The Inquirer covered their marriage in its “Philadelphia society” pages.

They had two children, Susan and Thomas, but their time together was tragically brief; Betty died in a car accident in 1957. As a student, she had been active in the College’s Little Theater Company, among several other groups and activities. With that in mind, Spock and others established a memorial fund in her name that made possible McCabe Library’s continued acquisition of dramatic recordings. The first works, including those by Shakespeare, Sophocles, and Samuel Beckett, arrived on campus in 1960.

In 1959, Spock married Patricia “Pat” Ellis, a software instructor for IBM. Pat was also a potter and later became a paralegal. They had two children, Jennifer and Jeffrey, and lived near the College, where they attended Swarthmore Friends Meeting.

At Penn Mutual, then Philadelphia’s largest life insurance company and one of the largest in the country, Spock pioneered the use of computers in the industry. He ultimately spent more than 30 years with the firm in several leadership roles, including executive vice president and acting president. He then served as managing director of a computer and management consulting firm, as well as a senior vice president of a regional insurance brokerage firm based in Media, Pa.

In 1982, Spock returned to his alma mater to serve on the Board of Managers, where his tenure included serving as chair of the audit committee and vice chair of the finance committee. He also served as Board secretary, including when the Board reached consensus to divest from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa, a topic that had dominated their discussions.

In announcing Spock’s 1989 appointment to the College’s senior staff, President David Fraser said: “The College is wonderfully fortunate to have attracted to the vice presidency a person of Bill Spock’s combined qualities of business skill, personal integrity, and appreciation of top-quality education.” In fact, Fraser had worked for months to persuade Spock to join his administration, something Spock did perhaps more out of duty than desire.

In that role, Spock oversaw the College’s endowment portfolio and the majority of non-academic departments on campus, including facilities, computing, dining, and the Scott Arboretum. In just a few years, Spock oversaw a 50 percent increase in Swarthmore’s endowment, a multi-million-dollar deferred maintenance effort, major computer and communications upgrades, and significant revisions of the College’s personnel and compensation policies, including an overhaul of the College’s pension plan that ensured every employee was enrolled.

During Spock’s tenure, the Lang Performing Arts Center was completed and the plan for what became Kohlberg Hall developed. He brought a credit union to campus and moved the bookstore and dining operations in-house after years of outsourcing. He also encouraged student participation in College committees, and sought their input on student services and the academic program. Significantly, the College’s budget remained in balance.

What made Spock so effective?

One clue is found in Spock’s frequent paraphrasing of Common Cause founder John Gardner: “A society which does not honor both its plumbers and its philosophers will soon find that neither its pipes nor its theories hold water.”

Spock came to the vice president role at a challenging time. The Bulletin described “a many-headed Scylla” that included not-unfamiliar issues such as increased expectations for programs and services, soaring costs of technologies and health care, the need for competitive salaries, massive deferred maintenance costs, and a drop in federal support — not to mention commitments to maintain a low student-faculty ratio and need-blind admissions.

It was not easy. At times, Spock kept department budgets flat, and salaries did not always keep pace with inflation. One year, five non-tenured faculty positions were eliminated due to attrition.

Perhaps Spock's secret weapon was his talent for recruiting. When hiring, he would ask himself: “Are they positive, enthusiastic, energetic? Do they have strong intellectual ability? This is much more important than what they know. Never hire people because they know something; hire them for what they can do.”

Larry Schall ’75, whom Spock hired as an associate vice president for administration, considers him a mentor and still draws upon the lessons he learned from him.

“Bill trusted me, and trusted so many others, to do the right thing when the right thing was not always the easy thing,” he says. “And for Bill, the right thing always started with treating people well and for giving the people who worked for him the room to learn and grow.”

Centennial Chair and Professor of Economics Ellen Magenheim, who served on committees with Spock early in her career, appreciated how open he was to hearing from everyone and how respectful he was of new ideas and differences of opinion. “I wasn't familiar with this style of leadership,” she says, “and found that he created an environment in which everyone could do their best work and be their best selves.”

In fact, Spock did so much so well, it seemed impossible at the time to find a single successor. So after he retired in 1995, his responsibilities were divided among several people.

Upon Spock’s retirement, President Al Bloom said: “The College is losing [one] of its central pillars of wisdom and strength — [an] individual who contribute[s] unstintingly to its educational mission, who model[s] its standards of excellence, [and] who share[s] the deepest affection and esteem of its entire community.”

“Bill was a truly decent and honorable man,” Schall says. “He accomplished so much in his life, yet never felt like he deserved accolades for any of that. He always preferred to give credit to others. Always.”

Once, reflecting on his near-lifelong affiliation with the College, Spock said he believed that core aspects of the College, such as the intellectual atmosphere and the close relationship between students and faculty, remained constant. He also challenged alumni to stay engaged with the College, even when they disagreed with it.

“We’re at the forefront of education,” he told the Bulletin in 1993. “Students are coming out of a changing society, and alumni should not criticize what the College is doing without learning more about it. If things seem to be going in a direction that doesn’t agree with their values, they should make sure they find out why. We mirror society, and in many ways we’re on the leading edge.”

On a subsequent occasion, he also encouraged his fellow alums to remember that “conditions change, and the ability to make adjustments must be a basic principle for a successful Swarthmore.”

Spock was a member of the American Academy of Actuaries and a fellow of the Society of Actuaries. A longtime Wallingford, Pa., resident before retiring to Maine, he served on the boards of the Friends Boarding Home in West Chester and Kendal Crosslands in Kennett Square, as well as the boards of the Helen Kate Furness Free Library and Riddle Memorial Hospital. In 1965, Spock started the Nether Providence Township soccer program, for which he hand-built the goal posts, recruited players, and participated as a referee. He also served on several volunteer committees for the Wallingford-Swarthmore School District.

“His kindness, intelligence, vision, insight, patience, nurturing, quiet sense of humor, friendship, and grace have always been a clear guide,” Hain says. “Those qualities have created a wonderful legacy, of which all who knew, worked for, and loved Bill are part.”

Citing the words of poet and writer John O’Donohue, Hain adds that Spock was “‘compassionate of heart, clear in word, gracious in awareness, courageous in thought, and generous in love.’ He left this world a better place.”

Put another way, and as noted in The Phoenix at the end of the 1951 men’s basketball season when Spock was the only senior on the team:

“For a little man, Billy, you sure leave a big hole.”