SYLLABUS

Click on links to get to information and questions about the authors and works

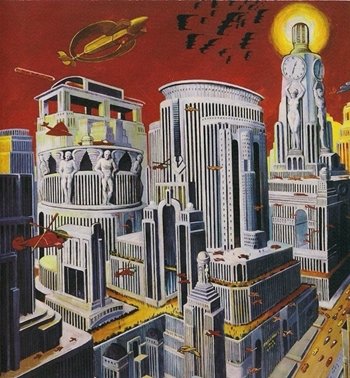

illustration from Zamiatin's WE

WEEK 1

January 23: Background, reading list, syllabus; discuss final reading

January 25: Nikolai Chernyshevsky, "Vera Pavlovna's Dream," pp. 248-58, and on Moodle; Fyodor Dostoevsky, "The Grand Inquisitor," on Moodle, and "Dream of a Ridiculous Man," pp. 276-90, on Moodle

Information and Questions on Dostoevsky and Chernyshevsky

(Optional readings for week 1: Konstantin Tsiolkovskii, "On the Moon: A Fantastic Tale," in Red Star Tales, pp. 38-77; Nikolai Fyodorov, "Karazin: Meteorologist or Meteorurge?", Red Star Tales, pp. 31-37; Nikolai Fyodorov, "The Question of Brotherhood..." - on Moodle; Valery Briusov, "The Republic of the Southern Cross," pp. 303-17; Bryusov, "Rebellion of the Machines," pp. 78-85)

Information on Tsiolkovsky and Fyodorov and questions for the optional reading

Information and Questions on Briusov

WEEK 2

January 30: Aleksandr Bogdanov, Red Star, introduction, pp. 1-16, and 17-140

Information and Questions on Bogdanov

February 1: Karel Čapek, R.U.R.

Information and Questions on Čapek and R.U.R.

Possible topics for the first paper, due February 22

WEEK 3

February 6: Evgenii Zamiatin, We

Information and Questions on We

February 8: Alexei N. Tolstoy, slim excerpt from "Aèlita, Queen of Mars," Worlds Apart, pp. 555-83, and on Moodle; clip from Yakov Protazanov's Aèlita; Aleksndr Belyaev, "Professor Dowell's Head," in Red Star Tales, pp. 113-157 .

Information and Questions on Aèlita

(Optional reading: Andrei Platonov, "The Lunar Bomb," pp. 158-80, on Moodle.)

Information and Questions for optional reading on Platonov

WEEK 4

February 13: Vladimir Nabokov, Invitation to a Beheading, Foreword and novel

Information and Questions on Nabokov and Invitation to a Beheading

February 15: Professor will be away at a conference; start reading Karel Čapek, The War with the Newts, and work on first paper

WEEK 5

February 20: Karel Čapek, War with the Newts, Book One, pp. 9-114

Information and Questions on Čapek's War with the Newts

FIRST PAPER DUE February 22!

February 22:

War with the Newts, Books Two and Three, pp. 117-241

Big Issues in the course to date

WEEK 6

February 27: Mikhail Bulgakov, "The Fatal Eggs," pp. 471-529 (on Moodle)

Information and Questions on Bulgakov's "Fatal Eggs"

February 29: Josef Nesvadba, "Expedition in the Opposite Direction," pp. 50-84, and "Inventor of His Own Undoing," pp. 142-164; Zamiatin, "On Literature, Revolution, Entropy, and Other Matters" (on Moodle)

Information and Questions on Nesvadba

WEEK 7

March 5: Ivan Efremov, Andromeda, presentations on sections

March 7: Ivan Efremov, Andromeda, continuing presentations on sections and discussion

(Optional reading if you want to see what kind of SF was getting published under Stalin: Alerksandr Kazantsev, “Explosion,” pp. 224-49)

Information and Questions on Kazantsev and Efremov

The self-scheduled midterm exam (due to me by March 8!) is on the course Moodle page.

SPRING BREAK

WEEK 8

March 19: Stanisław Lem, Solaris

Information and Questions on Lem and Solaris

March 21: Arkadii and Boris Strugatsky, Escape Attempt pp. 3-100 (on Moodle)

Information and questions about the Strugatskys and Escape Attempt

WEEK 9

March 26: Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Hard to Be a God

Information and questions about Hard to Be a God

March 28: Soviet SF stories: Vladlen Bakhnov, "The Fifth on the Left," pp. 142-55; Sever Gansovsky, "Vincent Van Gogh," pp. 52-118; Ilya Varshavsky, "No Alarming Symptoms," pp. 1-14 (on Moodle)

Information and Questions on these writers and stories

WEEK 10

April 2:

Arkadii and Boris Strugatsky, Roadside Picnic

Information and questions about Roadside Picnic

April 4: More Soviet SF stories: Olga Larionova, "Temira," pp. 1-30; Larionova, "The Useless Planet," pp. 80-121; Valentina Zhuravleva, "The Brat," pp. 31-40 (also available as "Hussy" in another translation, if you're interested in comparing them, pp. 143-151); Gennady Gor, "The Garden," pp. 107-25 (all on Moodle)

Information and questions about Larionova, Zhuravleva, and Gor

The longer paper (or equivalent project) is due on April 4!

WEEK 11

April 9: Stanisław Lem, The Cyberiad: Fables for the Cybernetic Age

Information and questions about Cyberiad

April 11: Kirill Bulychëv, "I Was the First to Find You," pp. 50-63, "May I Please Speak to Nina?" pp. 78-90, "Snowmaiden," pp. 103-13 (on Moodle)

Information and Questions on Bulychëv

WEEK 12

April 16: Lem, Futurological Congress, pp. 1-149

Information and questions on Lem's Futurological Congress

April 18: Vladimir Savchenko, "Mixed Up," pp. 352-98; Olga Larionova, "A Double Last Name," on Moodle

Information and questions on Savchenko and "Mixed Up"

WEEK 13

April 23: Viktor Pelevin, Omon Ra

Information about Pelevin and questions on Omon Ra

April 25: Daliya Truskinovskaya, excerpt from Doorinda, pp. 424-440; Sergei Lukyanenko, “My Dad’s an Antibiotic,” pp. 441-63

Information and Questions on Truskinovskaya and Lukyanenko

WEEK 14

April 30: Orest Stelmach, The Boy from Reactor 4

May 2: Final discussion.

SPECIAL PROJECT DUE ON MAY 2!

Let me know if you have questions about the Special Project.

Final Examination will be a three-hour self-scheduled written exam, posted on Moodle, due to me no later than May 16. (Or May 11, if you are a graduating senior at Bryn Mawr or Haverford.)