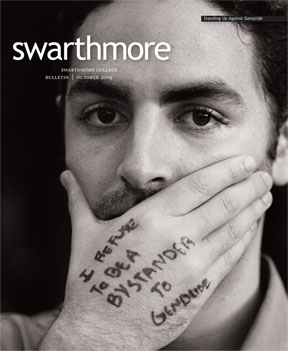

Beyond the Emotional Turmoil

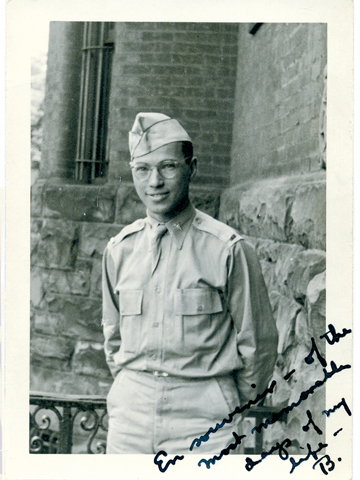

Gay Psychiatrist Bertram Schaffner ’32 Brings Compassion and Dignity to His Homosexual Patients.

Born in 1912, just after Woodrow Wilson was elected president, Bertram Schaffner grew up haunted by internalized homophobia. He transferred from Harvard to Swarthmore in 1929, thinking that being at a coed college might “cure” his homosexuality. Schaffner later became a psychiatrist, mentor to other gay therapists, and an avid collector of East Indian art.

The need to know what makes a person gay and to understand how to live as a gay man without suffering emotional turmoil has been a driving force in psychiatrist Bertram Schaffner’s life. For the past 60 years, the renowned physician has been in the forefront of historic developments for gays and lesbians. In 2001, the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy recognized him as a leader in the field who has made a major impact on the treatment of homosexuals and the work of gay therapists.

Schaffner’s world is small now—confined by illness and age to his art-filled home overlooking New York’s Central Park. Comfortably ensconced on a small couch in his living room—where a phone, calendar, paper and pens, and a glass of cranberry juice are within easy reach—he still sees two patients and graciously welcomes visitors to the third-floor apartment in which he has lived for 63 years. Clad in a pale green cotton robe and pajamas, he is eager, after a moment’s hesitation (born of a lifelong need for caution), to talk about his life.

For most of his 97 years, Bertram Schaffner felt compelled to lead a closeted life, never—until his 60s—voluntarily revealing that he is gay. The self-imposed isolation and admitted internalized homophobia led him to the field of psychotherapy with the desire to improve the lives of other gay people.

The Erie, Pa., native knew before entering grade school that he was gay. “Somewhere between the ages of 3 and 5,” he began to think of himself as homosexual and remembers being very comfortable with his feelings for other boys. In an interview with psychotherapist Stephen Goldman (“The Difficulty of Being a Gay Psychoanalyst during the Last 50 Years” in the 1995 book Disorienting Sexuality), Schaffner described his feelings: “I never thought of it as pathological. Rather, I always felt my feelings to be natural, ‘normal,’ and an intrinsic part of me.”

Normal, that is, until the parents of a playmate found notes that their son and Schaffner had exchanged about their interest in sex. “His parents forbade us to ever see each other again,” Schaffner says, “and I lost a friend forever.”

“When my parents learned of my activities,” he explained to Goldman, “I was made to feel wicked. I grew up feeling that I was someone to be avoided. I became fearful of being exposed as gay.” Although his father came to accept his son’s sexual orientation in the latter part of his life, his mother—living at a time when mothers were blamed for their sons’ homosexuality—was “morally shocked” and never fully accepted his sexual orientation.

“My isolation [as a child] was compounded by the fact that I was promoted three years ahead of my age group,” Schaffner says, “and sat in classes with 12-year-old children who would have nothing to do with a boy of only nine.” Later, as a freshman at Harvard, the age difference still set him apart from the other students, and the rejection intensified when fellow students began to suspect that he was gay. Convinced that he could “cure” his homosexuality at a coed institution, Schaffner transferred to Swarthmore in his sophomore year. He found the College to be friendly and warm, but he socialized little for fear of revealing his homosexuality.

One encounter at the College, however, changed his life. During his junior year, President Frank Aydelotte invited him to a tea honoring Rhodes Scholars and introduced him to a Central American physician who was working at a nearby pharmaceutical firm. Not only did the physician suggest that the English literature and philosophy major would make an excellent doctor, but the two—mentor and student—fell in love and had a relationship that lasted until the older man returned to his homeland two years later. “The cure did not take,” Schaffner remarks ruefully.

As a young physician, Schaffner had his first opportunity to help other gay men when he was drafted into the Army in October 1940. He feared being an enlisted man. “I did not know how I would manage living so close to other men,” he says. “Would I be accepted?” However by the time he was called to active duty upon completion of his residency in April 1941, Army regulations had changed so that enlistees with medical degrees automatically entered as officers.

As an Army lieutenant during World War II, Schaffner screened draftees for psychiatric fitness, appointing himself protector and caretaker of other young gay men faced with military service.

Lt. Schaffner, assigned to a base on Governor’s Island in New York Harbor, had the task of screening draftees for psychiatric fitness and appointed himself protector and caretaker of other young gay men faced with military service. It was clear, he recalls, that the Army wanted homosexuals identified and excluded from military service. “If a gay draftee was reluctant to serve in the army,” he says of the 60-some recruits that he examined each day, “or if I did not feel confident in his ability to do so, I would find a way to disqualify him from active duty without revealing his homosexuality. Also, when I encountered gay men who specifically wished to serve in the Army, I helped them to achieve that goal.”

After World War II, Schaffner found his homosexuality to be “a major, catastrophic liability” as he pursued his goal of becoming a psychotherapist. Being openly gay in the 1940s, Schaffner recalls, would have made returning to medical school impossible; during his medical training at Johns Hopkins University, he “lived in constant terror of my homosexuality being discovered.” (At the time, the American Psychiatric Association officially classified homosexuality as a mental illness.) In 1949—after being refused admission to both the New York Psychoanalytic Institute and the Columbia Psychoanalytic Institute because of his sexual orientation—he was accepted into the new, unorth-odox William Alanson White Institute of Psychoanalysis where he studied under Ralph Crowley, Erich Fromm, and Frieda Fromm-Reichmann.

Schaffner “yearned to be at peace with my own gay life and to help others do the same,” and so he dedicated his professional life to that purpose. Haunted by internalized homophobia, he was certain that if he revealed his sexual orientation and built a life with a male partner he would be ostracized socially and professionally. And in fact, early in his career, fellow psychotherapists who suspected he was gay or objected to his treating homosexuals often tended to shun him. Schaffner counseled his patients on dealing with society and worked to improve the self-esteem of both gay patients and other gay therapists. His compassion and commitment inspired several generations of psychoanalysts, according to Goldman, and prompted Schaffner to be founding chairman of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Committee on Human Sexuality; a member of the United Nation’s Expert Committee for Mental Health from 1948–1960; president of the Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists of New York in 1980; and—at age 82—the first openly gay supervising analyst for the William Alanson White Institute in 1994.

From the onset of the AIDS epidemic, Schaffner, although not infected himself, was on the front lines, caring for gay men and remaining in the forefront of psychiatrists dealing openly with gay and lesbian issues. In 1985, he and colleague Stuart Nichols established bi-weekly support groups for Manhattan physicians with HIV/AIDS; one such group continues to meet to this day in Schaffner’s apartment.

News of Schaffner’s approach to therapy—making all of his patients feel accepted and instilling in them the hope of leading a fulfilled life—attracted patients. Colleagues began sending gay patients to him, realizing the potential importance of those patients having a gay therapist. As his career progressed, Schaffner came to be recognized not only as a pioneer in treating homosexual patients but as a leading practitioner in his field, irrespective of sexual orientation. Today, his influence extends well beyond national borders.

Schaffner is hesitant to say that he has found a satisfying answer to the question of what makes a person gay and how to live as a gay man. Asked if anything has really changed for homosexuals in the last 60 years, he pauses—disappointment clouding his bespeckled, translucent face—before responding: “Much has changed, but fundamentally it’s still much the same.” Then, reflecting on his observation, he mentions that the American Psychiatric Association’s declassification, in 1973, of homosexuality as a mental illness was a positive change and that the present movement toward gay marriage is a welcome sign of progress. Today, he continues to look forward to even wider acceptance of gay people in society.

Email This Page

Email This Page

November 2nd, 2009 9:52 pm

In the late 1940's, as a teenage boy, I was a patient of Dr. Schaffner — treated for obsessive fears of death. I am not gay, and never knew until today that he is, but my son, Tobias Barrington Wolff, of whom I am tremendously proud, is a leading gay rights legal activist, and served as Chair of the Obama campaign's advisory committee on LGBT issues. Can it be that Dr. Schaffner's sensitivity to these issues somehow communicated itself to me, and made it possible for me to embrace my son's coming out to me in a supportive and loving way? I am thrilled to learn that Dr. Schaffner is still alive and well. I wish him all the best. Thank you for the story. — Robert Paul Wolff

November 2nd, 2009 9:53 pm

An addendum to my comment above. I was rejected by Swarthmore because I was in treatment with Dr. Schaffner, and ended up going to Harvard rather than following my sister, Barbara Wolff Searle, to Swarthmore.

November 3rd, 2009 1:28 pm

Robert Paul Wolff describes his teenage encounter with Dr. Schaffner in his blog. Scroll down a bit to the entry titled "A Remarkable Discovery." The blog was pointed out to me by my friend, Barbara Wolff Searle '52.

http://www.robertpaulwolff.blogspot.com

Jeff Lott

Editor

November 12th, 2009 11:46 am

Pamela Wade was both excited and proud to read the article about my cousin Bertram.

It was most interesting to to receive information about his life's work and the amazing contribution that he has made.

November 12th, 2009 2:49 pm

What a wonderful article about a remarkable man. Bert has been an inspiration to so many people all over the world and this feature will introduce him to those who have not have the opportunity to meet him personally. Bert is truly a national treasure.

November 12th, 2009 3:41 pm

Who should care about another person's sexual orientation! Who has the audacity to DICTATE what is right or wrong! Society? Society! Please!!!!!!

Bertram told me a story about an incident he encountered at home, when he was 13 yrs. old. He had come down the stairs and was about to turn a corner when he overheard both parents making disparaging remarks about his being "gay". How completely devastating this must have been!

Having married into the Weil/Schaffner family (now divorced), I can attest to the discrimination he faced amongst close family members. I never understood it. I never will. It lasted for too many years, but I am happy to say that it is no longer an issue.

It's time to accept and embrace our differences. Mankind, GROW UP!!!!!!!!

November 17th, 2009 9:15 pm

A terrific article. GAP (the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry) is indebted to Dr. Schaffner for leading the Committee on Human Sexuality. There is now and LGBT Committee, which is very active and continues the tradition of advocacy and scholarly activity he began.

Lois Flaherty is Immediate Past President of GAP.

November 20th, 2009 12:46 am

Bert Schaffner was an early inspiration in my coming out as a gay psychiatrist (and now psychoanalyst) in the late 1970s. His dedication, warmth and friendship eased the way for many of us. It is good to hear that his intelligence and humility still shine brightly.

February 1st, 2010 7:11 pm

Just three days after Bertram's passing I decided to google him.

First I watched the short wonderful film which was posted noting his passing and then just read your article.

I was a patient of Bert's starting about 1967 and going on for many, many years.

Afterwards we kept in touch.

I am a straight woman and learned about Bertram from my uncle and so I probably knew much more about him than his other patients. I also knew most of the information in your article as he had always given me many of the pieces written by him or about him.

But I love what you wrote and it did my heart good to be able to read about him today.

He is at peace. These past years have been difficult for him as he was grounded mainly to the apartment and he also did not understand why he was still living. But he continued to learn, to listen, to teach and to be a wonderful friend.

He will be missed by more than he realized.

Thank you…I hope to meet you at the memorial service whenever it is held.

Lee Goldé

February 2nd, 2010 12:10 pm

How sad to learn that Dr. Bert Schaffner has died.

Last July, during an interview in his Central Park apartment, I came to know what a unique and compassionate individual Dr. Schaffner was and how much he had helped homosexuals and others during his long life of service in the field of psychiatry. Even at the age of 97, he was engaging, inquisitive, and a delight to be with. I was fortunate to have come to know him during the last months of his life.

We all live in a better, kinder world because of his accomplishments.

To learn more about Dr. Schaffner's life:

http://www.funeraldigest.com/obituaries/?id=139133418

To view a short film: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXuZP7yZln4

Susan Cousins Breen

March 12th, 2010 9:09 pm

There will be a memorial event celebrating the life of Bertram H. Schaffner, M.D. at the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Auditorium (third floor) of the Brooklyn Museum on Sunday, May 9, 2010 at 2:00 p.m.

The museum is located at 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York 11238-6052.

As a Haverford graduate as well as a student of Bert's at the White Institute I am very moved by the article and tributes here. Bert was one of the teachers I most admired and loved. Luckily, even as his body failed him his mind remained clear and his emotional availability was undimmed. I will miss him.