Ostwald’s Odyssey Ends at 88

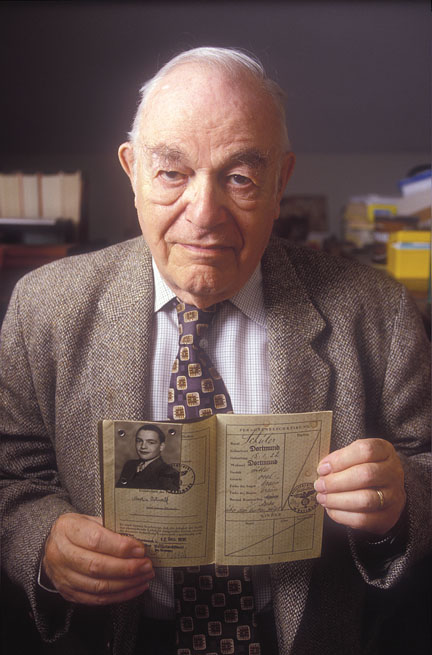

Martin Ostwald with his Nazi-issued passport from 1939. Through his mother’s efforts, he and his brother were sent via Kindertransport to Holland and then England. Despite his peripatetic existence as a refugee during World War II, Ostwald managed to continue his education.

The College was deeply saddened to learn of the April 10 death—due to heart failure— of Martin Ostwald, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor Emeritus of Classics. He was 88.

“Swarthmore has lost a towering intellect and a renowned teacher and scholar of the ancient Greek world,” wrote President Rebecca Chopp in a message to the campus community, which is adapted below.

Born in Dortmund, Germany, in 1922, Ostwald was the consummate gentleman with a refined, old-world sensibility that never failed to charm.

Ostwald’s plans to enter the rabbinate changed drastically after Nov. 10, 1938—Kristallnacht. Along with his father and younger brother, he was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to a concentration camp near Berlin.

Through his mother's efforts to secure them passage on a Kindertransport, he and his brother were released and sent first to Holland, then England. They never saw their parents again—his father died at the Terezin concentration camp and his mother at Auschwitz.

Throughout his peripatetic existence as a refugee during World War II, Ostwald managed to continue his education. At another refugee camp in Canada, where fellow internees started a camp school, he resumed his education and also taught Greek and Latin. While working toward his high school certificate, Ostwald made camouflage netting and knitted socks for the army.

With the backing of a Jewish fraternity, the University of Toronto accepted Ostwald and about 20 others from the camp. To assuage trustees worried about “enemy aliens” studying on campus while the country was at war, the group trained, in uniform, in the school's Canadian Officer Training Corps. He ultimately received a B.A. in classics from the University of Toronto in 1946, an A.M. from the University of Chicago in 1948, and a Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1952. Ostwald then taught at Wesleyan University for one year and at Columbia for seven before Centennial Professor Emerita of Classics Helen North recruited him to Swarthmore. “His influence on his students and colleagues was still unfolding,” said North. “Martin’s impact on the department, on the College and the classical world is beyond description. He was wise and kind and infinitely helpful to us all.”

For more than 30 years, Ostwald taught honors seminars that combined Germanic philological rigor with a relaxed, conversational style. For 20 of those years, he also maintained a joint appointment with the University of Pennsylvania. Even after his retirement in 1992, he continued to be a dapper presence on campus, walking most days from his home on Walnut Lane to his study carrel in McCabe Library to continue his writing and research.

Ostwald was a prolific scholar with wide-ranging interests and an accessible style. Among his many publications, some of the most notable include a translation of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, a handbook on the meters of Greek and Roman poetry, and several books on ancient Greek constitutional history: Nomos and the Beginnings of the Athenian Democracy; Autonomia: Its Genesis and Early History; and his magnum opus, From Popular Sovereignty to the Sovereignty of the Law, for which he received the Goodwin Award of Merit from the American Philological Association in 1990, an organization of which he served as president in 1987.

Additional honors include his election as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1991 and as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1993. He was an editor of The Cambridge Ancient History from 1976 to 1992, and a selection of his articles and essays was reprinted in 2009 by the University of Pennsylvania Press as Language and History in Ancient Culture. On Ostwald's retirement, Ralph Rosen '77 and Joseph Farrell, professors of classical studies at Penn, solicited and co-edited more than 40 critical essays from their mentor's former students and colleagues for a Festschrift in his honor. Ostwald also received honorary doctorates from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and from the University of Dortmund.

Ostwald discussed the experience of receiving the latter—and returning to his hometown—in a 2002 article in the Bulletin. He concluded: “My personal experiences show me how human beings are capable not only of degrading and dehumanizing themselves and their fellow men, but also that people have the potential to achieve greatness by creating monuments in art, literature, philosophy, and social justice that constitute the values of civilized life. In my case, the Greeks have shown the way, and it is their heritage that I have tried to pass on to my students.”

A service was held at the Swarthmore College Friends Meeting House on April 15, followed by a private burial in Har Jehuda Cemetery.

Ostwald’s wife, Lore, died on May 14. They are survived by their sons, David and Mordecai (Mark).

Email This Page

Email This Page