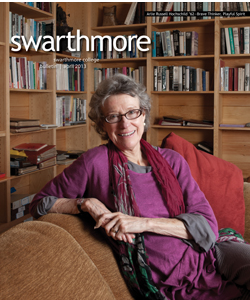

A Playful Spirit

While offering new insights on work, family, and emotional labor, Arlie Russell Hochschild ’62, still knows how to have fun.

It’s hard to believe it’s been more than 20 years since Arlie Russell Hochschild ’62 coined the term “the second shift” in her eponymous book, subtitled Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. She explored women’s paid work on the job, then, the other, unpaid, after-hours labor—baking cupcakes for our daughters’ next-day school party or making that meeting at the assisted-care facility we’re considering for mom’s next stage of life.

Arlie Russell Hochschild ’62 enjoys the lovely back garden of the Berkeley, Calif., house that she and husband Adam moved to a year ago, after decades of living in San Francisco. Photos by Seth Affoumado

The Second Shift, her third academic book, not only brought her public attention that very few scholars experience—she was a professor of sociology at the University of California–Berkeley then, is professor emerita now—but changed the landscape of our lives.

Her spotlight on the stress women feel from working two jobs was a wake-up call—for men as well as women.

But while more men today are sharing that shift work, says Hochschild, life has not become easier for families. “Men are in a more precarious economic situation, so it’s not so easy to be the good dad when you’re not sure that your boss is going to protect your job,” she says.

“There are some structural pressures that make it hard for people to turn things around,” she adds. “We would do better if families weren’t so under the gun, if we had the kind of policies they have over in Scandinavia [such as generous paid leave to handle family matters and subsidized child care].” (Scandinavia returns the admiration, as she has honorary doctorates from universities in Finland, Denmark, and Norway as well as from Swarthmore.)

Two years after The Second Shift came out, Hochschild wrote a piece for this magazine in which she posed the question: Who will do the work of the ’50s housewife in an era when most women work?

In 2012 came her answer. We’ve turned to the market economy to help us with “the time bind” (yes, she coined that term, too, in a 1997 book with that title). The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times explores the trend to pay for personal services we would have handled in the past—like planning an iconic wedding or, most extremely, having a baby.

Her latest consciousness-raising commentary on work, family, and emotional labor shows that, once again, Hochschild has the ability to introduce new catch phrases—and aha moments—into our vocabulary about social change.

Though the prospect of a sit-down with this woman who the American Sociological Association has hailed as one of the leading feminist sociologists of the last 30 years might be intimidating, that’s the last thing she is. But she is quite tall, so one does look up to her—literally as well as figuratively. She’s a fun dresser—flowy, drapy, purply. And fun doesn’t just apply to style. It’s clear that this woman likes to play.

Take Barbara Ehrenreich’s word for that. A former collaborator of Hochschild’s and the author of Nickel and Dimed writes in the foreword to At the Heart of Work and Family: Engaging the Ideas of Arlie Hochschild: “Arlie is one of the great, even iconic social thinkers of our time. Yes, her work is informed by dazzling intellect and deep moral passion … but she’s also done it because it was fun. … She likes to play.”

The Hochschilds pore over a manuscript as they pour coffee—a familiar routine in their balanced work/home life.

If you have any doubt, observe the 8-foot-high cardboard giraffe displayed in her house. She delighted in crafting it with the two daughters of son David ’93, who live just three blocks from her wood-frame home with its view of the Golden Gate Bridge, the Bay, and San Francisco from the bookshelf-lined room in the front of her house where she is being interviewed—not her customary role.

The article is supposed to be about her and her work, but she jogs your own emotional memory, and you find yourself rolling out personal second-shift stories: when you were a single mother, and you, too, outsourced when you could—hiring a woman to pick your son up from school and take him to baseball practice, your daughter to ballet lessons.

Her openness, her genuine interest in you tempts you to break down the normal divide between subject and interviewer. You see why her books are so authentic and so palpable and why her interview subjects often wind up as friends.

Take Rose, for example. In The Outsourced Self, she was the personal assistant of Norma, an affluent stay-at-home mom in New York. Rose handled household tasks as well as emotional labor for Norma. It was Rose who picked up Norma’s kids from the airport, took them to doctors’ appointments, and made excuses to a salesperson when Norma damaged a dress brought home on approval.

Though her work with Rose ended years ago, Hochschild has maintained close contact with her former subject, serving as a support when Rose’s only child died.

Likewise, when Hochschild traveled to the Akanksha Infertility Clinic in Gujarat, India, to interview pregnancy surrogates—poor Indian women who were being paid to carry fetuses for infertile American couples—she connected with a journalist for the Hindustan Times, Aditya Ghosh. He accompanied her to the largest baby farm in the world—and in turn, she helped him enter graduate school in sociology.

“He is now in the United States doing a Ph.D.,” she says smiling. “He’s got his wife and child here, so that all worked out beautifully. I feel so good about it. He helped me a lot, and I was able to reciprocate.”

Gift exchange is a very important concept to Hochschild. Of circulating gifts—Ghosh helping her, and she helping him, all free of charge—she says, “There’s a beauty in that, you know? There’s a friendship now, and he and his family may come and visit us.”

In speaking of gift exchange, Hochschild invokes the work of Lewis Hyde, author of The Gift and a recent speaker at Swarthmore (see adjacent story).

“Hyde talks about the spirit of the gift as something that continues through time,” she says, leaning forward, earnestly. “With any commercial transaction, it’s, ‘I give you this, you give me that. We’re done.’ There’s no abiding memory attached to it. But memory puts such beauty into life, and it’s also an existentially anchoring thing—to have memory in our relationships. The spirit of the gift as something that goes on and on is very important, and I thank Hyde for lifting that out. You could say that I’m trying to make room for that spirit in my work.”

The generosity of spirit Hochschild displays with her interview subjects and others connected to her books extends as well to colleagues.

When her son David ’93 was attending Swarthmore, Hochschild came for a visit. Joy Charlton, then a junior professor but now executive director of the Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility as well as professor of sociology, was teaching the class Gender, Power and Identity, using the just-published The Second Shift as a text. A student in Charlton’s class was a friend of David’s and invited mother and son to drop by.

Charlton recalls how “the door slowly opened, and Arlie and David quietly came in. I remember how my heart pounded. My professional heroine had just walked into my classroom. Arlie headed for the back, but I, of course, immediately brought her forward to be in conversation with the students. Having the author of a book we had read together, someone so well-known in the field, be in dialogue so graciously and unexpectedly was an empowering experience for all of us. It was a wonderful gift.” Later, Hochschild returned for a semester as a Lang Visiting Professor for Issues of Social Change.

While her interpersonal style is nonjudgmental, so is the tone of her writing. She likes to take her readers on “an intellectual journey,” she says.

“I say, ‘Look at this problem with me—figure out how you feel about it with me; turn it around from all sides with me on this journey. Let’s explore.’ I think of the book almost like a meditation on where we are [in the market economy]. And I say, look, ‘I’m outsourcing, too. I’m there with you.’ ”

with me on this journey. Let’s explore.’ I think of the book almost like a meditation on where we are [in the market economy]. And I say, look, ‘I’m outsourcing, too. I’m there with you.’ ”

More so than any of her other books, Outsourced Self is about Hochschild as well as society at large. Her search for her own outsourcer—a caregiver for her aunt who lived in Maine—weaves through the book. By making herself a player in this evolving social phenomenon, she’s signaling, she says, “You’re not just an insect being scientifically inspected by the white-coated scientists.”

The book is resonating in ways she never would have predicted. This warm and gentle woman has been invited to speak in November at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas at Australia’s Sydney Opera House. Kicked off in 2009 with an opening address by the late British author Christopher Hitchens, the annual festival has also featured the likes of WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange and feminist author Germaine Greer. Though the 24-hour flight sounded daunting, Hochschild accepted the request, because, “It was just too interesting.”

Other unexpected outcomes of the book include its selection as the first-year reader for Stanford next fall and an invitation to consult at Google on the challenges of work/life balance of its female employees.

Though some may think she’s achieved quite enough and deserves time to just sit back and play with the grandkids (she still manages plenty of that), Hochschild is on to her next book projects.

First, there’s How’s the Family?, a book of essays due out in August from the University of California Press. The title essay, she says, “looks at the impact of neoliberal policies (deregulation, service cuts, lower and regressive taxation that exacerbates the class gap) on the second shift. If we don’t regulate junk-food ads on children’s TV programs and Coke machines in schools, we add to the probability of childhood obesity,” she says. “That means more trips to the doctor, daily injections, food monitoring—additions to the second shift. If we cut unemployment insurance and food stamps, we also add great anxiety to the second shift. Like other aspects of public life, public policy ‘comes home.’ ”

Besides the forthcoming essays, Hochschild is pursuing a new book project (Outsourced Self took seven years), which explores the emotions behind political beliefs. In February, she headed down to Louisiana for her fourth interviewing trip.

“It’s just too much fun being in the field,” she says of her nonretirement. “I think we both feel that. We get a kick out of it, and we’re just so lucky.”

The “he” in the “we” is Adam Hochschild, founder of Mother Jones magazine and the author of Bury the Chains and other memorable books of historical narrative nonfiction, most recently To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion: 1914–18. (His next book is on the Spanish Civil War.)

Arlie met Adam at a Quaker work camp in Spanish Harlem when she was 20 and he was 17. Though they aren’t practicing Quakers, she says they are “Quakerish. We like the ethic, the spirit.” Quaker values provide “some of the ingredients for mobilizing around important issues and basing a sense of community on moral questions,” she explains.

Her appreciation of Quaker values also drew her to Swarthmore as a sophomore transfer student. Daughter of a United States diplomat, Hochschild began college in New Zealand, where her family was posted after an earlier two-year stint in Israel. It was her experience of being a 12-year-old outsider at that first post that attracted her to sociology.

“I was the only American in the school and two heads taller than everyone, and I didn’t speak Hebrew, and I wore dresses that were fancier than anyone else’s,” she says. “It was the worst and the very best thing that ever happened to me, because I just had to realize that my road was a tiny one and this was a bigger world, and I didn’t fit into it. It was such a privilege to be exposed to so many different ways of living, and it really made you question your own.”

Once at Swarthmore, she continued her interest in international relations by majoring in the subject and joining the Political Action Group and Peace Corps Committee. She pursued social action, as she had in high school. When she met Adam, she was dating a Swarthmore Quaker, but her affinity for Adam won out. The Hochschilds did civil rights work in Vicksburg, Miss., before marrying in 1965.

“Adam is a wonderful person, very kind and thoughtful, and that was apparent from the beginning,” she says. “I thought, ‘Well, if I can just master that last name …” she says with a laugh.

Much as they love and respect each other, they can put on their critics’ hats, working over a manuscript side by side at the kitchen table.

“It’s a gift—a tough critique is like a good friend,” she says. “You say, ‘I see what you’re trying to do, but let’s see—why don’t you start over here?’ Sometimes I think I’m going on a wild-goose chase and think, ‘Where’s that going to fit into this?’ He says, ‘The data will tell you. Don’t worry. Just get deeper in.’”

Thankfully for all of us, she keeps digging deeper.

Email This Page

Email This Page

April 29th, 2013 12:59 pm

Arlie, being modest and 'Quakerish' might throw out my suggestion, but I will make it anyway: she is the greatest living sociologist. Her writing is weighted as thoughtfully as the best pianist and she sees in the smallest things phenomena of the greatest global content and see in global phenomena how each person might be implicated - all without loss of hope. I am not aware of any sociologist - ever- who could accomplish this so well. Not one. Open her books at random and pick a paragraph and absorb it right there… read them backwards or forwards; or read a page from one and a page from another and it still makes easy sense. Now that is real hard for a sociologist to accomplish - for a whole series of reasons.

It comes through….