Krystyna Zywulska

The Making of a Satirist and Songwriter in Auschwitz-Birkenau is Discovered Through Camp Mementos.

Krystyna Zywulska, born Sonia Landau to Jewish parents in Lódz, Poland, walked out of the Warsaw ghetto in August 1942. She joined the resistance as Zofia Wisniewska and provided aid to Jews in hiding, assuming yet another fictitious identity when arrested by the Nazis in June 1943. Two months later, she was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau as a Polish political prisoner. There, she began to write poems and songs, becoming one of a group of amateur poets and musicians who created “unofficial” art.

Krystyna Zywulska is best known as the author of Przezylam Oswiecim (I Survived Auschwitz), a candid and moving account of life and death in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Published in Poland in 1946, Zywulska’s memoir (listen: The Making of a Satirist) represents one of the earliest and most significant contributions to Polish literature on the Holocaust. Less known, but no less important, are Zywulska’s songs and poetry created during her imprisonment. These works have lain dormant in neatly labeled folders in the Aleksander Kulisiewicz Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington for the last 15 years. Some have been tucked away further and longer still, in the archives of the Auschwitz Museum in Poland.

Their neglect has at least two explanations. Until very recently, musicologists have demonstrated a bias against “nonprofessional” utilitarian music, deeming songs created by ordinary prisoners in the camps as aesthetically inferior to so-called "art music.” Prisoners’ songs, like Zywulska’s, have also endured “marginalia” status because they challenge the persistent notion that prisoners were victims solely acted upon by their Nazi oppressors, a historical canard that has risen from the desire to honor the dead and a fear of undermining the enormity of the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Yet Zywulska’s remarkable works offer valuable insight into the daily experiences and cultural activities of prisoners in the Nazi camps, sensitively reflecting an insider's perspective on camp events in the process of their unfolding. They are, in the essence of things, critical reportage, the stuff of historical documentation. As important—perhaps more so—they also reveal the unlikely birth of a literary and satirical talent, a prisoner-turned-writer in the crucible of death. In this respect, Zywulska’s camp creations also affirm art to have been—for some prisoners at least—a fundamental aspect of their humanity, a natural means to satisfy the life of the mind or to comfort the heart.

Krystyna Zywulska was born Sonia Landau in Lódz, Poland, either on Sept. 1, 1914, or May 10, 1918, depending on which sources you consult. (Here begin the most basic questions concerning her identity.) Raised in an atmosphere shared by many urban, Polish-speaking assimilated Jews, Zywulska’s upbringing was decidedly secular; though the family preserved some familial traditions around the Jewish holidays, they did not attend services at synagogue or keep kosher. There was family music-making—Zywulska’s mother sang beautifully, while her father played mandolin. At times, Zywulska would join them at the piano. Zywulska considered herself a Communist, less perhaps out of conviction than a desire to be in step with the predominant politics of Lódz’s youth in the interwar period.

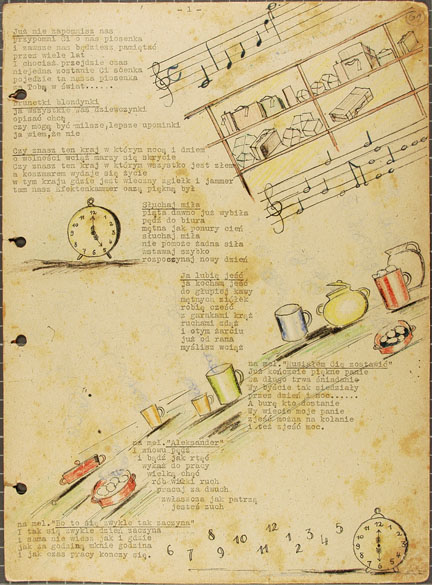

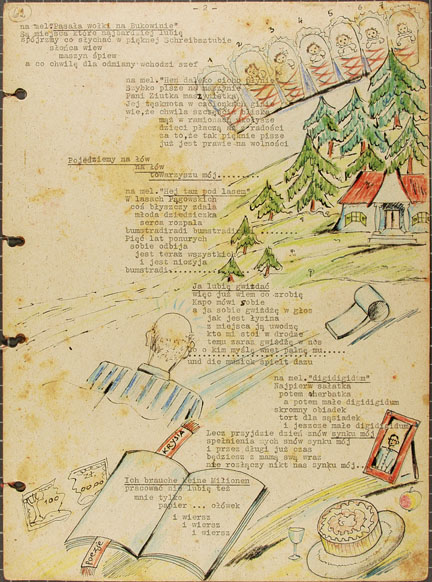

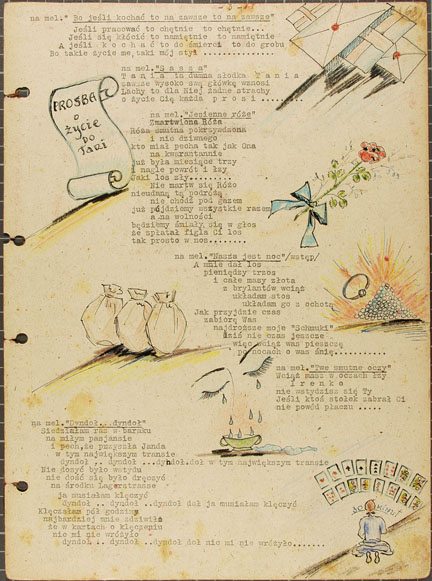

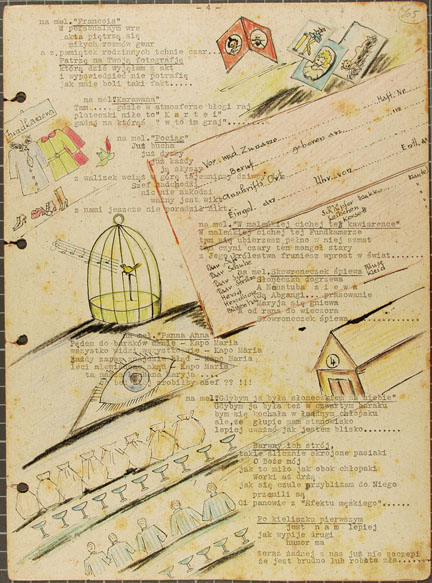

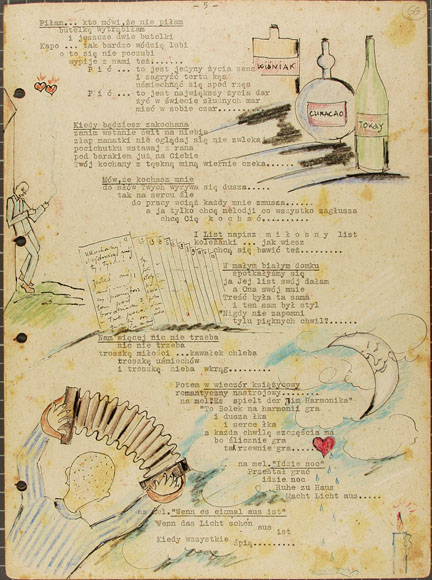

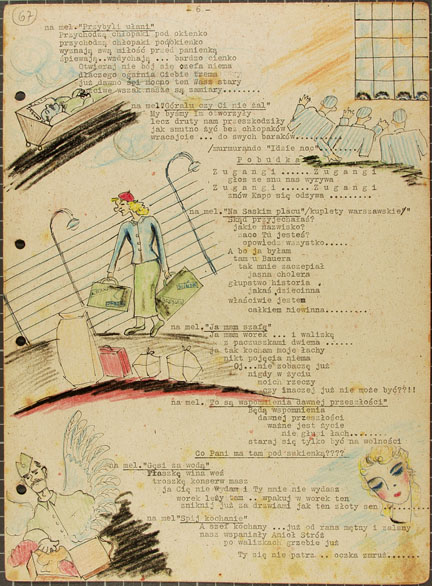

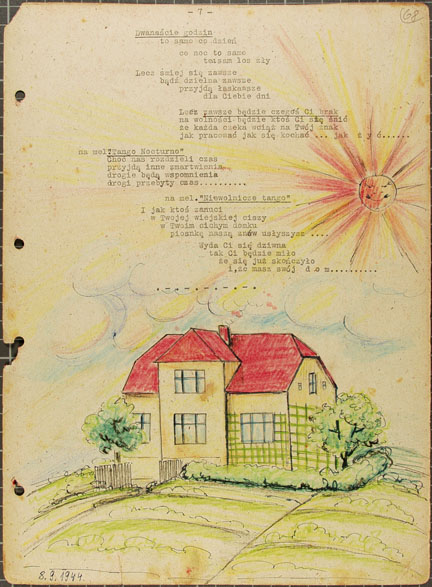

Among the lengthiest compositions to survive the camps is a string of 54 song fragments set to an array of Polish folk melodies and prewar popular tunes that in one way or another humorously immortalize Zywulska’s friends. Typed on seven pages and illustrated by a fellow inmate (as shown here in the images of those pages), it was performed by a quartet of women and presented as a name-day card to the prisoners’ block captain.

After completing a Polish-language Jewish gymnasium in Lódz, Zywulska began law studies in Warsaw, in 1938. According to her own account, she was entirely unconcerned about the antisemitic climate at the university. Following the Nazi occupation of Poland a year later, she returned home to be with her father, mother, and sister, Basia, who was 8 years younger. As the Nazi persecution of Jews in Lódz grew more violent following the city’s incorporation into the Third Reich, Zywulska returned to Warsaw hoping to arrange documents that would prevent her family's relocation to the Lódz ghetto.

Though her attempts to help them failed, they somehow managed to get out, making their way to Warsaw, where they were eventually relocated to the ghetto there in 1941. Weighing the chance of survival against the certainty of deportation or death by starvation, Zywulska daringly walked out of the ghetto with her mother, in broad daylight, on Aug. 26, 1942. She left behind her father in order to have a better chance of survival, a decision that tormented her until her dying day. On the “Aryan side,” she assumed different identities and joined the Polish resistance. As Zofia Wisniewska, she provided aid to Jews in hiding and to at least one German deserter by counterfeiting identity cards and documents.

On June 21, 1943 she was arrested and taken to the infamous Gestapo headquarters on Szucha Avenue in Warsaw. Under interrogation, she assumed the ficticious identity of Krystyna Zywulska so as not to implicate her fellow conspirators. She was transported to Pawiak prison, also in Warsaw, then two months later to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she was registered in the camp on Aug. 23 as Polish political prisoner number 55,908.

On June 21, 1943 she was arrested and taken to the infamous Gestapo headquarters on Szucha Avenue in Warsaw. Under interrogation, she assumed the ficticious identity of Krystyna Zywulska so as not to implicate her fellow conspirators. She was transported to Pawiak prison, also in Warsaw, then two months later to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she was registered in the camp on Aug. 23 as Polish political prisoner number 55,908.

Though according to her own account in Przezylam Oswiecim, she had never before written poetry, in Birkenau Zywulska began creating verses at first in order to endure the endless roll-calls to which prisoners were subjected. Fellow inmates—eager to learn her poems—memorized and disseminated them beyond an immediate circle of friends. Among the most popular was “Wymarsz przez bramçe” (“March Out Through the Gate”), which first sarcastically records the reality of marching out to labor details beyond the camp, then calls on her fellow inmates to persevere, presenting them with a vision of liberation day, when she and her comrades will finally have a chance to take revenge. It is a powerful, provocative poem, one that cunningly usurps control of the Nazi's very own sadistic, ubiquitous, deafening march to deliver a potent message of revenge—a march turned against its master.

But “Wymarsz” could not have been written were it not for an earlier Zywulska poem “Apel” (“Roll Call”), that in large part saved her life. A well-positioned “older“ prisoner named Wala Konopska heard the poem and, struck by its honesty and insight, sought out its author, offering protection. Konopska saw to it that Zywulska received treatment for typhus and helped destroy records of an internal camp Gestapo interrogation that revealed Zywulska was Jewish—all to save her “camp poet.”

But “Wymarsz” could not have been written were it not for an earlier Zywulska poem “Apel” (“Roll Call”), that in large part saved her life. A well-positioned “older“ prisoner named Wala Konopska heard the poem and, struck by its honesty and insight, sought out its author, offering protection. Konopska saw to it that Zywulska received treatment for typhus and helped destroy records of an internal camp Gestapo interrogation that revealed Zywulska was Jewish—all to save her “camp poet.”

By February 1944, once again thanks to Konopska’s interventions, Zywulska was working in the Effektenkammer—storage facilities for personal effects confiscated from arriving prisoners—considered among the best jobs in the camp. Prisoners assigned to this type of labor squad were safeguarded against harsh physical work outdoors and had ample opportunity to illegally obtain food, clothing, and other valuables. Yet for all of their privilege, the Effektenkammer workers, located directly adjacent to crematorium IV, could not escape the sight, screams, and stench of the relentless, daily mass killings taking place just a few yards away.

Zywulska also could not escape the constant fear of her Jewish identity being discovered by her fellow inmates. Though this mattered none to Wala Konopska, it was not at all clear to Zywulska that her fellow workers in the Effektenkammer kommando would be as sympathetic. As Zywulska recalls: “I was afraid … I was not only a Jew, but then I was also a Communist—nothing could be worse, right?” Friend and fellow survivor Anna Palarczyk explains, “Somehow we knew about this—I’m not sure how—but no one talked about this. She was Krysia, and that was that.” But for Zywulska, there was also the impossible condition of witnessing the mass murder of fellow Jews, and the private fear of being found out to be one of them.

Zywulska also could not escape the constant fear of her Jewish identity being discovered by her fellow inmates. Though this mattered none to Wala Konopska, it was not at all clear to Zywulska that her fellow workers in the Effektenkammer kommando would be as sympathetic. As Zywulska recalls: “I was afraid … I was not only a Jew, but then I was also a Communist—nothing could be worse, right?” Friend and fellow survivor Anna Palarczyk explains, “Somehow we knew about this—I’m not sure how—but no one talked about this. She was Krysia, and that was that.” But for Zywulska, there was also the impossible condition of witnessing the mass murder of fellow Jews, and the private fear of being found out to be one of them.

It was under these circumstances that Zywulska wrote some of her most provocative poems. “Wycieczka w nieznane” (“Excursion into the Unknown”) is one such work. Written during summer 1944, it very poignantly juxtaposes the peaceful sounds and images of nature and life beyond the camp with the grotesque, death-ridden environment of Birkenau. “Excursion” rapidly spread through the camp, finding its way eventually to Auschwitz I. There, inmate Krzysztof Jazdzynski, presumably moved by the content of the poem and wishing to preserve it, set it to music, modifying Zywulska's text to fit the melodies of the international hits “Santa Lucia” and “Gloomy Sunday.”

Other verses by Zywulska were from their inception conceived for singing—and for consolation. “Wiazanka z Effektenkammer” (“Medley from the Effektenkammer”), among the lengthiest compositions to survive the camps, is a string of 54 song fragments set to an array of Polish folk songs and prewar popular tunes that in one way or another humorously immortalize her friends from the Effektenkammer. Typed on seven pages, decorated with multicolored drawings by fellow inmate Zofia Bratro, and signed by 72 prisoners, Zywulska’s “Wiazanka” was performed by a quartet of women and presented as a name-day card to block Kapo Maria Grzesiewska on Sept. 8, 1944. The inscription on the title page reads: “For our dear Maria on her name day, from all of those with whom she shared the good and the bad, and whom she helped to endure—as a memento.”

Other verses by Zywulska were from their inception conceived for singing—and for consolation. “Wiazanka z Effektenkammer” (“Medley from the Effektenkammer”), among the lengthiest compositions to survive the camps, is a string of 54 song fragments set to an array of Polish folk songs and prewar popular tunes that in one way or another humorously immortalize her friends from the Effektenkammer. Typed on seven pages, decorated with multicolored drawings by fellow inmate Zofia Bratro, and signed by 72 prisoners, Zywulska’s “Wiazanka” was performed by a quartet of women and presented as a name-day card to block Kapo Maria Grzesiewska on Sept. 8, 1944. The inscription on the title page reads: “For our dear Maria on her name day, from all of those with whom she shared the good and the bad, and whom she helped to endure—as a memento.”

Zywulska’s medley departs dramatically from the sober reportage of “Excursion into the Unknown”—the urgent need there to psychologically process mass murder. So light-hearted and playful are these short characterizations of Zywulska’s Effektenkammer friends that one could mistake them for something created in an entirely different setting than a death camp. Indeed, after the war, Zywulska herself was reluctant to disseminate the work, wary of the possibility that uninitiated readers would draw the wrong conclusions about life as a prisoner in Birkenau. The shifting texts register kaleidoscopically the everyday world of the Effektenkammer but also lead consolingly to visions of future happiness, to life after captivity.

Toward the end of 1944, Zywulska also composed one other parody song that I am aware of called “Marsz o wolnosci ” (“March of Freedom”). For the music, Zywulska borrowed the tune from a popular Soviet mass song, “Moskva mayskaya” (“Moscow in May”). Just a few months later, “March of Freedom” was sung by prisoners including Zywulska during their forced evacuation from Birkenau. Zywulska escaped from this so-called “death march” on Jan. 18, 1945.

Toward the end of 1944, Zywulska also composed one other parody song that I am aware of called “Marsz o wolnosci ” (“March of Freedom”). For the music, Zywulska borrowed the tune from a popular Soviet mass song, “Moskva mayskaya” (“Moscow in May”). Just a few months later, “March of Freedom” was sung by prisoners including Zywulska during their forced evacuation from Birkenau. Zywulska escaped from this so-called “death march” on Jan. 18, 1945.

The exact number of Zywulska’s camp poems and songs remains uncertain, but at least 32 complete texts survive. All are invariably marked by a vivid realism, some also by a quality of direct and sober reportage. And while sarcasm and irony prevail, Zywulska’s compositions seldom lapse into despair. Rather, they most often exude life—specifically, Zywulska's own will to live—and deliver a powerful message of resistance.

After the war, Zywulska remained in Poland, married Leon Andrzejewski, a prominent official of the Urzad Bezpieczenstwa, the Office of Security, or more plainly, the Communist Secret Police, and had two sons, one who turned out not to be Leon’s. She worked as a writer, mostly of satire, contributing pieces to the magazine Szpilki and fashioning satirical monologues commissioned by illustrious Polish actors such as Alina Janowska as well as directly for Polish Radio. She was also a successful songwriter. In 1966, her “Zyje sie raz” (“You Live Once”), with music by Adam Markiewicz, became an instant hit in Poland when it was debuted by the Polish chanteuse Slawa Przybylska, herself a child of the Holocaust. While it is easy to understand the appeal of the song—a timeless narrative of love, love lost, and perseverance nonetheless—to know its author's life is to understand and appreciate the song’s meaning that much more deeply. It is Zywulska’s credo, one formed by a life of risks taken, over and over again.

In 1970, Zywulska moved to Düsseldorf to be with her sons, who had earlier emigrated to the West as a result of the 1968 anti-Semitic campaigns in Poland. Asked by the Polish psychologist and scholar Barbara Engelking near the end of her life whether Krystyna was her real name, she replied, “In my life, when it comes to such topics, there is nothing ‘true,’ my dear.” But in truth, she was “Zosia” to family and friends from before the war and “Krysia” to her friends who survived Birkenau. They loved her all the same.

In 1970, Zywulska moved to Düsseldorf to be with her sons, who had earlier emigrated to the West as a result of the 1968 anti-Semitic campaigns in Poland. Asked by the Polish psychologist and scholar Barbara Engelking near the end of her life whether Krystyna was her real name, she replied, “In my life, when it comes to such topics, there is nothing ‘true,’ my dear.” But in truth, she was “Zosia” to family and friends from before the war and “Krysia” to her friends who survived Birkenau. They loved her all the same.

She died on Aug. 1, 1992, and is buried in Germany as Zofia Zywulska Andrzejewski. Those who had been closest to her, both family and friends, remember Zywulska as a woman who loved to laugh, sing, and jest. Perhaps befitting a woman endowed with such optimism and spirit—as well as a gift for pictorial description—in the last decade of her life, without training and with impressive success, Zywulska took up painting, fulfilling a life-long desire.

Assistant Professor of Music Barbara Milewski is at work on a book devoted to exploring amateur, unofficial music-making in the Nazi camps through the lives and compositions of three survivors. In a recent lecture, she explained: “At present, no such detailed critical study exists. Moreover, there tends to be a misunderstanding among some scholars of the conditions that fostered music of this sort. Specifically, the ability or inability of prisoners to engage in music creation is narrowly thought to be attributed to privileges or deprivations of group affiliation, be it national, political, or religious.

“Such constrained views of victim groups, however, obscure the fact that prisoners often had rather more complicated roles, relationships, and identities in the camps that allowed for greater interaction and the possibility to participate in shared musical life. Categorical approaches, whatever the motivation, are, of course, not unique to Holocaust and World War II research. But the urgency to undo simplifying claims here is, I think, greater, for at stake is the memory of countless victims for whom we must now, somehow, speak.”

Milewski majored in political science at Bowdoin College. She received an M.A. from SUNY–Stony Brook and a Ph.D. from Princeton University.

Email This Page

Email This Page

March 5th, 2010 5:43 pm

Dear Prof. Milewski,

Are you in contact with Krystyna Zywulska family?

My family and hers knew each other in Warsaw, before 1970.

Her son Jacek Andrzejewski is a well known artist.

http://www.kamienikon.jaaz.pl/page/article/13

I am glad to know that people are interested in her art.

Inga Karliner

March 21st, 2010 9:22 pm

Dear Ms. Karliner,

Thank you for your response to my article. My apologies for getting back to you only now. I would very much like to speak with you about Krystyna Zywulska, if you would be interested to do so. I am in close contact with both of her sons and they have been tremendously helpful to me in my research. I would very much appreciate any knowledge you may be able to share about your relationship with Zywulska after the war. If you are interested, please let me know how I might be able to get in touch with you to talk further.

Respectfully,

Barbara Milewski

January 31st, 2011 12:16 pm

Dear Prof. Milewski,

the first time I heard about Krystyna Zywulska was during my holidays in Austria, where I met Malgosia Ostrowski her doughter in law.

I never met anyone who survived Auschwitz. All the things she told me where awful, horrible and also impressing what Krystyna did. Krystyna ist the most fascinating woman I heard about. Malgosia told me that she met women who where with Krystyna in Auschwitz and that they still know her poems and songs by heart.

I had to see them. Last year I visited Irena Wisniewska and Alina Dambrowska in Warsaw. These are two very nice and warmhearted ladys. I filmed the intervierws and made a short documentary. If You are interested to see it, I would love to send it to You.

Best Regards

Silvia Kreuer