Physical Grace, Rare Deeds, Creative Genius

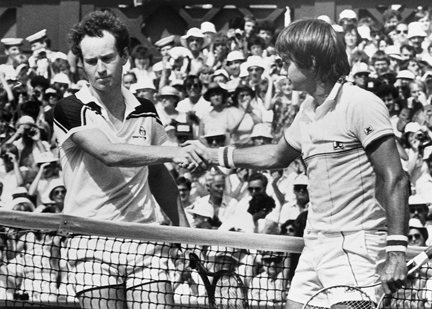

John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors shake hands after McEnroe wins the men’s singles at Wimbledon 1984.

Stephen Tignor ’92, High Strung: Björn Borg, John McEnroe, and the Untold Story of Tennis’s Fiercest Rivalry, Harper, 2011

To reflect upon a work about untold tennis stories, I had only to turn to the weathered photographs on the cinder-block walls of my tennis office at Swarthmore, and there he is: All-American Stephen “Tigs” Tignor, on the Ed Faulkner Courts, May 1990, leading his team to an NCAA National Team Championship in Division III.

With long hair flowing, well-worn blue baseball cap turned irreverently backwards, tossing arm gracefully and perfectly extended, he stands, racket poised to strike his biting lefty serve.

I recall saying to him before that crucial semi-final against Kalamazoo College: “Tigs, let’s play it safe, get the ball in play and look for a secure opening before attacking”—a style that had always worked for him. Tigs ignored my advice and hit for the lines, taking huge risks by advancing forward to net, winning in straight sets, and shyly exiting the court almost before his teammates had finished their warm-ups.

That was Tigs on the court—creative, unpredictable, eschewing obvious norms in favor of riskier alternatives. In his new book, we see something of this athlete as artist, the discipline behind the craft, the writer’s eye for detail and skill at invoking image, the respect for journalistic accuracy, and the scholar’s reliance on historical and social research.

Tignor’s approach in High Strung is reminiscent of Norman Mailer’s literary journalism, such as his epic psychological analysis of Muhammad Ali in The Fight (1975). In the hands of Mailer, Ali becomes a figure of immense intellectual gifts. So do Tignor’s subjects—McEnroe, Connors, and Borg—all come to assume an interior life of complex motives and drives; a world of intentions, doubts, and emotions; a psychic framework of immense complexity sketched in and revealed by the observations and soaring imagination of the author.

Often, admired athletes live their lives of physical grace and rare deeds without ever giving expression to the creative genius inside, leaving it to outsiders and sideline admirers to supply the voice that explains the self. Tignor, a writer who has experienced the emotional void of real competitive tennis, has taken the novelist’s risk of linking action with insight, athletic brilliance with personal fears, biography with public excellence.

Many sport books portray stars and their singular lives. High Strung pays its debt to a reading public thirsting for the superficial reality of stardom, but it also becomes a starting place for broader discovery—that of historical and social analysis. We encounter a somewhat crude, reductionist pairing of social class and tennis to explain complex personalities: Thus, Jimmy Connors is labeled “brash” because he is from working class East St. Louis, Ill., where the Victorian gentleman’s code of sportsmanship was unknown.

Sport historians see a break in the ethos of modern sport occurring somewhere in the 1880s, when the working class expropriates modern sport, displacing Victorian manners with a new partisan ethos that was aggressive, commercial, and loud—sport as open conflict.

The history of tennis as socially exclusive —with its roots in British aristocracy, extended worldwide through the empire—explains the isolation of a sport that, according to Tignor, did not enjoy mass consumption until the 1970s and 1980s. Connors, McEnroe, and Borg became emblems of this new image—more media stars and commercial icons than sport warriors parading a leveling democratic message. These glimpses into the social history of sport and tennis—asides to the drama of the center court—inform and educate the reader, elevating this work above simple sport histories or biographies.

It took many decades before the new ethic fully penetrated the Ivy walls of the tennis establishment—an historical journey Tignor describes in his narrative. Jimmy Connors was the first player to shatter the amateur façade of “gentility, of class, of gentlemanly diffidence,” replacing it with tennis as psychic combat in a public arena.

John McEnroe was at first shy and prone to self-doubt but soon learned to apply an appallingly boorish style, borrowing on the security of his background of privilege and nouveau elite roots. Borg developed a singular, baseline tactical approach to tennis derived from his childhood socialization into the sport, the lonely hours of hitting ball after ball against his garage door in his working-class neighborhood in Sweden. These individual differences are interesting, but their connection to sociology as explanation is less compelling.

Yet, the descriptive historical narrative of on-court actors Borg and McEnroe, supplemented by forays into the players’ mental states, seems completely appropriate. We also learn much about tennis—the contrasting playing styles of the serve-and-volleyer and the baseliner; the equipment; court surfaces; and codes of ethics, on and off court, of the players. This rich blend of so many factors adds to our understanding and appreciation of the sport, its actors, and the location of the institution in our society.

Just as Tigs broke the rules to win a championship back in the 1990s, Tignor seems to have shattered a few literary norms with this dense, complex book, an historical journey into the psychic dimensions of the exposed, singular athlete, chasing individual achievement while courting failure. His admiring old coach would like to reveal that he knew Tigs would eventually find his voice—a discovery of which all of us are beneficiaries.

—Michael Mullan

Professor of physical education and sociology and men’s tennis coach

BOOKS

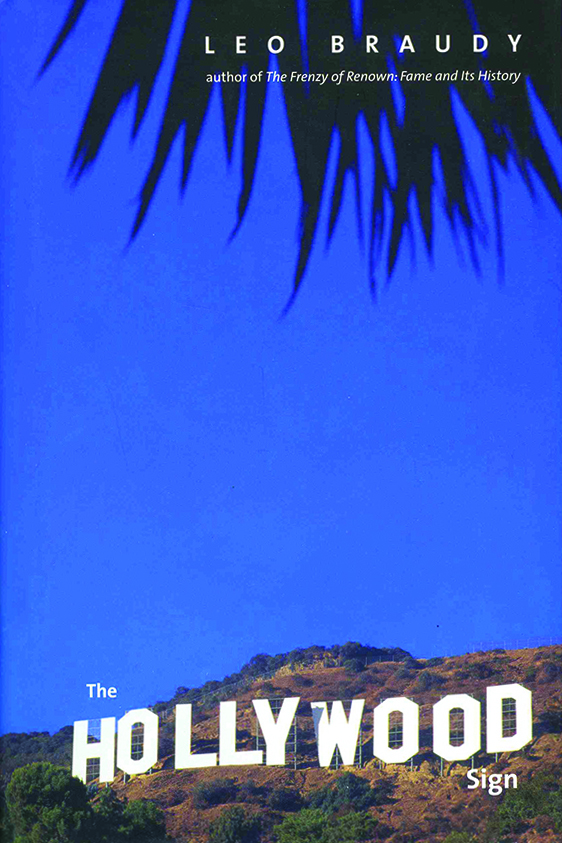

Leo Braudy ’63, The Hollywood Sign, Yale University Press, 2011. Erected in 1923 as an advertisement to tout the real estate development of Hollywoodland, the gigantic sign of white blocks set into a steep hillside evolved into an emblem of the movie mecca, international symbol of glamour and star power, and icon of American culture. As he traces the history of the sign, Braudy also offers a fascinating look at the rise of the movie industry from the silent-movie era through the development of the studio system that helped define modern Hollywood.

Leo Braudy ’63, The Hollywood Sign, Yale University Press, 2011. Erected in 1923 as an advertisement to tout the real estate development of Hollywoodland, the gigantic sign of white blocks set into a steep hillside evolved into an emblem of the movie mecca, international symbol of glamour and star power, and icon of American culture. As he traces the history of the sign, Braudy also offers a fascinating look at the rise of the movie industry from the silent-movie era through the development of the studio system that helped define modern Hollywood.

Michael Casher and Joshua Bess ’00, Manual of Inpatient Psychiatry, Cambridge University Press, 2010. This compact clinical manual is convenient for use on the psychiatric ward. With chapters organized around the diagnoses found in psychiatric units, it addresses the common questions and issue that clinicians face in day-to-day psychiatric work with inpatients.

Robin Chapman ’64, The Eelgrass Meadow, Tebot Bach, 2011. Poet and scientist Chapman offers a collection of beautiful and moving poems, in which, according to Jesse Lee Kercheval, “her tone glides between elegy and rallying cry, delight at discovery and sorrow at what is to come. This book will inform and transform your vision of our shared world.”

Pamela Haag ’88, Marriage Confidential: The Post-Romantic Age of Workhorse Wives, Royal Children, Undersexed Spouses and Rebel Couples Who are Rewriting the Rules, HarperCollins, 2011. Haag writes about the untold side of marriage—the semi-happy ambivalence that lurks below the surface of most marriages and the truth that one or both partners may feel as if something very important is missing. With in-depth research and doses of humor, the author tells firsthand accounts as well as stories of contemporary marriages where spouses seem more like friends than lovers and where romance and passion are assailed from all sides.

Pamela Haag ’88, Marriage Confidential: The Post-Romantic Age of Workhorse Wives, Royal Children, Undersexed Spouses and Rebel Couples Who are Rewriting the Rules, HarperCollins, 2011. Haag writes about the untold side of marriage—the semi-happy ambivalence that lurks below the surface of most marriages and the truth that one or both partners may feel as if something very important is missing. With in-depth research and doses of humor, the author tells firsthand accounts as well as stories of contemporary marriages where spouses seem more like friends than lovers and where romance and passion are assailed from all sides.

Ken Hechler ’35, Soldier of the Union, Pictorial Histories, 2011. Civil War letters from George and John Hechler, ancestors of the author and soldiers in the 36th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, describe the tribulations of the war, from camp life at Parkersburg and Summersville, to the brutal battlefields of Lewisburg, Antietam, Chickamauga, and others. The Ohioans’ letters described the valiant efforts of the regiment as well as the people and places in what would become the State of West Virginia.

The Fight for Coal Mine Health and Safety, Pictorial Histories, 2011. In November 1968, Congressman Hechler willingly set aside his own personal safety and jeopardized his political career by standing up for the coal miners in his district and throughout the nation who faced danger and death in the workplace. Hechler pushed through Congress the most far-reaching occupational health and safety legislation ever enacted.

Stephen Henighan ’84 (translator), The Accident, by Mihail Sebastian, Biblioasis, 2011. This translation of one of the most celebrated modern European authors tells a story of love and emotional devastation, beginning when a young woman is rescued from an accident by a troubled young man and she decides to rescue him back.

Stephen Henighan ’84 (translator), The Accident, by Mihail Sebastian, Biblioasis, 2011. This translation of one of the most celebrated modern European authors tells a story of love and emotional devastation, beginning when a young woman is rescued from an accident by a troubled young man and she decides to rescue him back.

Ambassador James Hormel ’55 and Erin Martin, Fit to Serve: Reflections on a Secret Life, Private Struggle, and Public Battle to Become the First Openly Gay U.S. Ambassador, Skyhorse Publishing, 2011. In this thoughtful narrative, the author describes his journey from lost boy to openly gay man—his daily struggle with life in the closet, of being a professional with a wife and children, and of his despair and that of his loved ones, then the freedom of finally coming out, becoming an antiwar activist, battling homophobia, losing friends to AIDS, and becoming an ambassador during the Clinton administration.

Caitlin Murdock ’94, Changing Places: Society, Culture, and Territory in the Saxon-Bohemia Borderlands, 1870–1946, The University of Michigan Press, 2010. This transnational history depicts the birth, life, and death of a modern borderland—the cross-border region between Germany and Habsburg Austria and, after 1918 between German and Czechoslovakia—and of frontier people’s changing relationships to nations, states, and territorial belonging.

Helen Schneider ’91, Keeping the Nation’s House: Domestic Management and the Making of Modern China, UBC Press, 2011. Rattling the assumption that home economics training lies far from the seats of power, this book reveals how Chinese women helped to build modern China one family at a time. Focusing on the vision and aspirations of the women who shaped a discipline, Schneider offers a gendered perspective on the past and reveals how women intellectuals dealt with the transition from Nationalist to Communist eras.

Email This Page

Email This Page