Beyond Pink and Blue

Move over, women’s studies—there’s a new way to think about gender and sexuality.

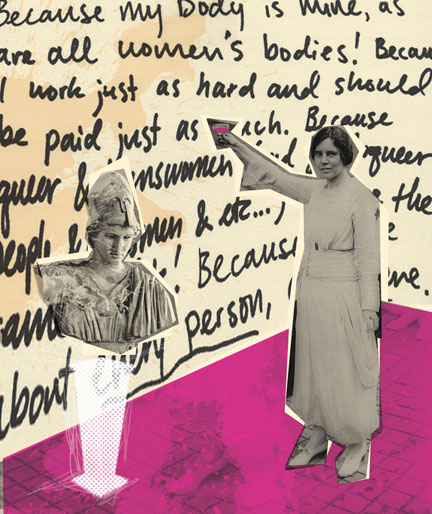

Alice Paul ’05 (right) celebrates the passage of the 19th Amendment while the goddess Athena looks on. The words are from a 2008 project originated by Urooj Khan ’10 in which students identified themselves as feminists and explained why. Students pictured on the following pages participated in the project.

When Women’s Studies was established as a field of academic inquiry 40 years ago, humans had a relatively simple, binary view of gender: One was either female or male. One’s sex was inextricably linked to one’s reproductive organs. True, hermaphrodites existed as a kind of murky in-between, but that was resolved by assigning them at birth to either the pink team or the blue team.

This essentialist view of gender was challenged in 1990, when feminist philosopher Judith Butler published her groundbreaking book Gender Trouble. She argued that gender is a learned social behavior that we each perform.

Swarthmore students today cite Butler regularly when they talk about gender as “a fluid state of identity.” It seems almost obvious to this generation that femininity and masculinity are nothing more than social constructs that we act out—and that there are many more than two gender choices. The dismantling of the long-held binary view about gender was offered as a reason by professors and students as to why Swarthmore’s 23-year-old Women’s Studies Program should officially change its name in spring 2008 to Gender and Sexuality Studies (GSS).

The name change was no easy matter. It entailed a laborious two-year bureaucratic process by the Women’s Studies Program’s steering committee, which solicited input from every possible stakeholder—alumni, students, administrators, and even Tri-college partners Bryn Mawr and Haverford.

The massive effort was led by then-program coordinator Sunka Simon, associate professor of German and film and media studies, and current program coordinator Bakirathi Mani, associate professor of English literature. They and others analyzed syllabi, held open discussions, and even hosted a symposium on the topic. Finally, in February 2008, they presented their report to the College’s curriculum committee, which reviewed the material, grilled the steering committee for an hour, and approved the name change for presentation to the full faculty for a vote.

“I put on my Viking helmet and was ready to do battle,” Simon jokes, “but no one spoke against it. The vote passed.”

Women’s Studies was no more; Gender and Sexuality Studies was born.

But why go to all that effort to change the name of an interdisciplinary program that was a relative newcomer to the college? A respectable average of eight students a year have concentrated, minored, or special majored in women’s studies, which is comparable to the numbers in black studies, another of Swarthmore’s 13 interdisciplinary programs. Women’s Studies had no lack of courses. Every department in the College except mathematics, engineering, and astronomy cross-listed courses in Women’s Studies. So what was the problem with the name “Women’s Studies” that led the program’s steering committee to put so much effort into changing it? Did substituting the word “gender” for “women” erase a piece of Swarthmore’s history of struggle for women’s equal voice in academia?

The Evolution of Knowledge

“The categories of ‘women’ and ‘men’ are difficult and complex and open to question,” says Luciano Martínez, assistant professor of Spanish and Latin American studies, who will be coordinator of GSS in 2010–2011. “How do you define men and women—as something transhistorical? Decades ago, scholars and people in general used to have this idea that there was an ‘essence’ that defined what it meant to be a woman, regardless of location, language, culture, and historical and political contexts. Now we know that different countries or cultural areas understand these categories differently. For example, the idea that women are defined by maternity—that being a woman means being a mother—is a cultural construction. And it can be very oppressive for women who don’t want to be mothers, or can’t be. Between the 1950s and today, what it means to be a woman and a man has changed. We need to see that and take it into account. We are trying to establish gender and sexuality as fundamental categories of social and cultural analysis and to study how ideas about gender and sexuality shape roles, identities, and social norms in a broad range of geopolitical and historical contexts. Therefore, the name ‘women’s studies’ was far too narrow.”

For those who came of age before the postmodern ethos expanded the menu of self-identities, there may be some cognitive dissonance when the word “women” is used as a theoretical construct rather than indicating a category of human beings who have been subject to marginalization, discrimination, disenfranchisement, repression, suppression, and oppression. Forty years ago, women’s studies was brewed in a political cauldron. The women’s movement of the 1970s (often criticized as being primarily white and middle-class) included a personal process of consciousness-raising and a critical lens that exposed sexism (what is now referred to as “gender inequality”) and the power hierarchy (the patriarchy) that oppressed women. The battle to legitimize women’s studies at Swarthmore and through-out academia was viewed as a political struggle against systemized sexism, and not a theoretical disagreement. Women were breaking the glass ceiling in academia and demanding respect for their ideas and scholarship and access to positions of power. The new name of the program is a shift away from looking at women as a special category.

For those who came of age before the postmodern ethos expanded the menu of self-identities, there may be some cognitive dissonance when the word “women” is used as a theoretical construct rather than indicating a category of human beings who have been subject to marginalization, discrimination, disenfranchisement, repression, suppression, and oppression. Forty years ago, women’s studies was brewed in a political cauldron. The women’s movement of the 1970s (often criticized as being primarily white and middle-class) included a personal process of consciousness-raising and a critical lens that exposed sexism (what is now referred to as “gender inequality”) and the power hierarchy (the patriarchy) that oppressed women. The battle to legitimize women’s studies at Swarthmore and through-out academia was viewed as a political struggle against systemized sexism, and not a theoretical disagreement. Women were breaking the glass ceiling in academia and demanding respect for their ideas and scholarship and access to positions of power. The new name of the program is a shift away from looking at women as a special category.

Women’s Studies is not the first program or department to change its name at Swarthmore. In 1984, physics and astronomy were separate departments. Today, they have become one department because much of astronomy is based on quantum physics. But in the case of Women’s Studies, the name-change is more fraught because the program served as a symbol of Swarthmore’s history of struggle for women’s equality.

“Changing the name might seem to imply that women have already achieved equality and, therefore, no longer need to be given special consideration or a separate space to nurture their ideas,” says Nazima Kadir ’97, who minored in women’s studies and is working on a doctorate in anthropology at Yale. “The reality is, in academic life, women are very marginalized. Women tend to be in ‘casualized’ teaching positions or administration, which are lower in the hierarchy. Men tend to be published more and get more professional recognition. Tenure-track positions go to men more often than to women. By taking the word ‘women’ out of Women’s Studies, and turning it into ‘gender,’ there is a danger that the activist women’s movement is being removed from the equation.”

When Emily Nolte ’07, a financial consultant in Atlanta, came to Swarthmore, she already considered herself a pro-choice feminist. “I think older generations did such a good job fighting for women’s equality that we can expand the scope of the program beyond just women,” she says. Nolte, who minored in women’s studies, says that the ideas she had about feminism and women’s space when she first arrived at Swarthmore “were more related to my parents’ generation. These days, it’s about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual-queer (GLBTQ) rights, and looking at how ethnicity plays into gender equality.” When she was asked by the steering committee to give her opinion on changing the name of the program, Nolte was all for it. “The name may have changed,” she says, “but if you go and sit in on a class on any day, you will hear professors talking about sexism and feminist theory. But now they’re also talking about gender theory. We’re trying to move forward together in a more inclusive way.”

Growing National Trends

Swarthmore may have been a latecomer to women’s studies, but it’s among the first to adopt a new name and broader agenda for the program. Allison Kimmich, executive director of the National Women’s Studies Association (NWSA), estimates that 15 percent of women’s studies programs around the country have changed their names (although some have kept the word “women” or “feminist” in the title). She believes campus politics is a key reason it’s been happening—and also financial considerations. Joining women’s studies programs with like-minded programs such as queer studies or sexuality studies saves money.

Beverly Guy-Sheftall, who has been director of women’s studies at Spelman College since 1971, has a different take on the growing trend. “On many campuses, I think this is mainly about men,” she says. “We know from the data that male students will take women’s studies classes if the word ‘woman’ isn’t in the title. Institutions that don’t have separate queer studies programs often offer those courses through women’s studies. Queer studies has privileged the gay male experience on too many campuses. In fact, I would say it’s mostly about white gay maleness. They also look at gender, but looking at gender doesn’t mean being sensitive to sexism or racism. These days, it’s all getting lumped together, and feminist theory and the feminist lens are getting pushed aside.”

Queer studies, GLBT studies, and sexuality studies are separate fields with distinct professional associations and academic journals. At many large universities, they each have their own separate programs. At a small school like Swarthmore, there aren’t enough resources to support so many different programs. Since Women’s Studies was already looking at analyses of gender and sexuality, GLBT, sexuality, and queer studies courses were cross-listed in the program. When the steering committee gathered all the syllabi of the courses cross-listed with women’s studies and evaluated them in 2008, they discovered that the vast majority focused on the intersections of gender, sexuality, and queer identity. “Only a handful used the word ‘women’ in the title,” says Sunka Simon.

“It’s a question of practicality,” says Jean-Vincent Blanchard, professor of French and former coordinator of the Sager Symposium on GLBT issues, who teaches in the formerly named Women’s Studies Program. “Students were clamoring for programs that pertained to sexuality and gay and lesbian studies.”

Martínez, whose work focuses on Latin American lesbians, gays, and transvestites and the U.S. Latino experience, concurs. He believes that the name change is appropriate for Swarthmore’s particular situation. “The academic field is dictating how we organize knowledge. As professors, we are concerned with continuing to inspire students and also giving them degrees that are up-to-date within the larger academic world.”

But it doesn’t look as if women’s studies is under threat of imminent extinction. The NWSA saw a 48-percent jump in professional membership since 2005, in part because more and more universities are graduating Ph.D.s in the field. Many signs indicate that the field of women’s studies is thriving.

However, Martinez may have a point, says Kadir. “In the academic world these days, women’s studies is definitely not as hip as queer theory.” Kadir says that the term women’s studies might even seem a bit “old-fashioned.”

Jack Aponte ’02, a technology consultant for nonprofits in the New York area who concentrated in Women’s Studies, says it might have been “a nice, symbolic gesture to keep the word ‘women’ in the program name to acknowledge the history behind it.” But Aponte, who identifies as a genderqueer-butch also likes the new name, because it more accurately describes the classes s/he took. “We went far beyond just looking at women’s history. We explored the ways gender functions in society and the fact that there are more than two genders. We learned feminist theory but also studied gender, queerness, and sexuality. It was functioning as gender and sexuality studies anyway, so it makes sense to start calling it what it is,” Aponte says.

Dina Kopansky, a junior who is special-majoring in gender and sexuality studies, agrees that the program had already become a home for queer and transgender students. “The feminist lens and feminist theory is where we start in our classes, but it’s so much bigger now. Gender, sexuality, and queer theory are all part of it, and the Gender and Sexuality Studies Program is a safe place to explore these ideas.”

Like many students who come to Swarthmore and go through a coming-out process around their sexuality and gender identity, Aponte discovered that academics and personal growth were intertwined. The Women’s Studies Program became a place where Aponte could start to think more expansively about gender and further explore and understand queer identity. “Women are still tremendously underrepresented, and it’s important to make space for women,” says Aponte. “But I’m glad the program is expanding beyond just women because gender and sexuality are linked. We need to recognize the shared locus of oppression—that women, trans folks, and queer folks are all oppressed because they deviate from gendered prescriptions about what one should do, how one should act, what one should look like, or whom one should love. Women were able to carve out some space at Swarthmore and empower themselves, and that’s great. But it’s important for oppressed people to share what little power we have.”

Like many students who come to Swarthmore and go through a coming-out process around their sexuality and gender identity, Aponte discovered that academics and personal growth were intertwined. The Women’s Studies Program became a place where Aponte could start to think more expansively about gender and further explore and understand queer identity. “Women are still tremendously underrepresented, and it’s important to make space for women,” says Aponte. “But I’m glad the program is expanding beyond just women because gender and sexuality are linked. We need to recognize the shared locus of oppression—that women, trans folks, and queer folks are all oppressed because they deviate from gendered prescriptions about what one should do, how one should act, what one should look like, or whom one should love. Women were able to carve out some space at Swarthmore and empower themselves, and that’s great. But it’s important for oppressed people to share what little power we have.”

Interdisiplinary Program Names

There are additional interdisciplinary programs at Swarthmore that focus on other minority groups, such as Latin Studies and Black Studies. Although there are intersections and abutments in theory and content, there has never been discussion of the two programs merging to become, for example, racism studies. Likewise, the Asian Studies, Islamic Studies, and German Studies programs have no intention of joining forces to become a unified Cultural Studies Program.

Allison Dorsey, associate professor of history and coordinator of the Black Studies Program, says there was talk several years ago about changing the name of Black Studies to Africana Studies, to embrace a broader, more diasporic understanding of the experience of people of African descent throughout the world. “We have a growing student population from the diaspora—Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Haiti,” she says, “and the students are always pushing us to give them more material on the myriad cultures, traditions, and languages of the African diaspora. These were all very good reasons to change the name, but there were two reasons we didn’t do it. First, it would have been false advertising. We didn’t want a name that suggested we offered substantial course material about it when in actuality we didn’t. And second, black studies as a field has a history rooted in political activism that goes back 50 years. The concept of blackness and a black aesthetic came into being at a certain moment in time, and it suggests a certain sense of solidarity and vision of a new politics that is about freedom and opportunity for people of African descent. In the end, we decided that was worth preserving, so we continue to be called Black Studies.”

Backlash

It may be that the alumni and faculty who are most sad to see Women’s Studies change its name are those who participated in the women’s movement of the 1970s. Despite its problematic history of being dominated by white, middle-class, educated women, the movement still accomplished remarkable social changes, and many women and men are proud to call themselves feminists. But the F word has fallen out of favor with the younger generation—even among those who are staunch supporters of a woman’s right to choose and equal pay for women.

Urooj Khan ’10 is a notable exception. Last summer, the political science major who is double-minoring in Islamic studies and gender and sexuality studies, had an internship with the Feminist Majority in Washington, D.C. When she returned to campus, she helped to revive Swarthmore’s chapter of the national advocacy group. She and other chapter members set up a photo project last April. “We had a table in Parrish, and, as people walked by, we asked them if they identified as feminists,” she says. “If they did, then we snapped Polaroids of them and asked them to write down what feminism meant to them. We posted 30 or 40 photos on a board under the heading ‘This Is What a Feminist Looks Like.’ Later in the semester, we had a discussion about feminism that included dozens of students and professors.”

Psychology Professor Jeanne Marecek attended the event and ended up in a small group with nine students and Scott Gilbert, Howard A. Schneiderman Professor of Biology. Gilbert has done considerable work on the feminist critique of his field. Marecek was amazed that not a single woman in the group said she would publicly identify herself as a feminist. One woman reported that a male friend told her that feminists were “man-haters.”

“If the Women’s Studies Program had changed its name to Feminist Studies, it would have been the kiss of death!” says Marecek. She explained to her discussion group that feminism was also about the study of masculinity. A man in the group looked blank and asked, “What’s there to study about masculinity? What can you want to know about men?”

Marecek replied, “I look at how men and boys produce their masculinity and how prescriptions and proscriptions about manly behavior constrain their everyday lives.”

“Scott told them, ‘To me, feminism is about politics,’ and I said, ‘To me, it’s about social critique and social justice.’ The students looked starry eyed,” says Marecek. “This is what the backlash against feminism has left us with. It’s the neo-liberal idea that all women need is to be independent. In that way of thinking, piercing your eyebrow because you want to do it comes to seem like a ‘feminist’ act. What’s missing is the part about changing social systems and cultural structures, challenging the illusion of choice and freedom, and analyzing the constraints that are placed on people. It’s hard for young people to see this because what they have seen is a commercialized version of feminism that is individualistic and apolitical.”

Clearly, the dialogue about equality has changed in 23 years. Without talking about feminism, it’s hard to talk about sexism and patriarchy, says Khan. “There are people here—especially women of color—who believe in women’s rights, but they don’t call themselves ‘feminists’ because women of color have historically been excluded from the movement. I’ve seen firsthand how women of color are excluded and pushed to the margins in feminist spaces, so I understand their perspective. But I believe it’s important to reclaim the feminist movement as something that women of color can be a part of in a real way. We need to take it and make it our own.”

Clearly, the dialogue about equality has changed in 23 years. Without talking about feminism, it’s hard to talk about sexism and patriarchy, says Khan. “There are people here—especially women of color—who believe in women’s rights, but they don’t call themselves ‘feminists’ because women of color have historically been excluded from the movement. I’ve seen firsthand how women of color are excluded and pushed to the margins in feminist spaces, so I understand their perspective. But I believe it’s important to reclaim the feminist movement as something that women of color can be a part of in a real way. We need to take it and make it our own.”

Men, Transgender, and Women’s Studies

Something everyone can agree with is that women’s studies was never supposed to be just for women. Men and transgender people also benefit from engaging with the thorny questions of gender, power, and identity. But despite the fact that men have chaired the Women’s Studies Program at Swarthmore and taught courses in it, among the 176 students who minored, special-majored, or concentrated in it between 1986 and 2007, there were just five men. The problem was, most men didn’t see women’s studies as being relevant to them.

For example, Jeanne Marecek used to teach a course called “The Psychology of Women.” “One September, a male came to the class,” she remembers. “He said, ‘I’m taking this class because I want to understand my girlfriend.’ I realized the title implied that women have a separate, unique psychology, so I changed the name of the course to Psychology and Women.” Later, she changed it to Psychology and Gender, and more male students signed up.

It’s imperative to challenge masculinity and maleness as the unquestioned norm, says Urooj Khan. “When we talk about gender or feminism, the conversation is about what it means to be a woman. If you’re a man, you think there’s nothing to be examined about you because you’re normal.”

Lori Kenschaft ’87, who concentrated in women’s studies and later earned a Ph.D. in American studies with a focus on gender, sexuality, and social thought, wondered back in 1986 why the program wasn’t called Gender Studies. “Focusing exclusively on women’s experience of femininity lets men off the hook,” she says. “It puts blinders on how men’s behavior is affected by gender. Thinking practically, we can’t transform gender structures in society without men questioning masculinity.”

This may be the argument that convinces Second Wave feminists that replacing the word “women” with “gender and sexuality” is good for the cause. Even so, the name change will still be experienced as a loss by some who proudly remember the women’s movement and its bold critique of sexism and the patriarchy.

This may be the argument that convinces Second Wave feminists that replacing the word “women” with “gender and sexuality” is good for the cause. Even so, the name change will still be experienced as a loss by some who proudly remember the women’s movement and its bold critique of sexism and the patriarchy.

Gender and sexuality studies is engaged in different explorations, deconstructing gender and blasting open our binary thinking. It may not be what the founders of Women’s Studies would have hoped for back in 1986, but feminism—or whatever we’re allowed to call it these days—is still a presence at Swarthmore.

“No one is saying the work of feminism is done,” says Bakirathi Mani, coordinator of the Gender and Sexuality Studies Program. “We have just expanded the context so that students can begin to understand how gender politics, power structures, and feminism affect everyone.” That, after all, was always the ultimate goal of the women’s movement.

Laura Markowitz majored in comparative religion, minored in English and anthropology, and concentrated in Asian studies. She is a producer for Arizona Public Media, Tucson’s National Public Radio and PBS affiliates. Although Women’s Studies wasn’t around when she was a student at Swarthmore, she was active with the then-named Alice Paul Women’s Center. She currently serves as chair of the College’s Tucson Connection. “Beyond the Pink and the Blue” is Markowitz’s fifth feature for the Bulletin. She was also an essay contributor to The Meaning of Swarthmore, 2004.

Laura Markowitz majored in comparative religion, minored in English and anthropology, and concentrated in Asian studies. She is a producer for Arizona Public Media, Tucson’s National Public Radio and PBS affiliates. Although Women’s Studies wasn’t around when she was a student at Swarthmore, she was active with the then-named Alice Paul Women’s Center. She currently serves as chair of the College’s Tucson Connection. “Beyond the Pink and the Blue” is Markowitz’s fifth feature for the Bulletin. She was also an essay contributor to The Meaning of Swarthmore, 2004.

Email This Page

Email This Page

December 25th, 2010 6:34 am

Great article