Art as a Matter of Public Safety

It’s OK for us to take care of ourselves and to create what we find to be beautiful or true.

“Like any artist with no art form, she became dangerous.”—from Sula by Toni Morrison

Facing stacks of dirty dishes, unopened mail, and haughty preteen critics, I need Toni Morrison’s wisdom to embark on my next artistic adventure. Before I push-pinned her words to my bulletin board, I’d considered my own art merely a narcissistic indulgence. Now I understand that it’s actually a matter of public (and private) safety.

I haven’t found myself in all the sticky situations Sula did; but, like her, I recognize a certain restless energy that can lead me astray when it lacks a healthy outlet. Those times in my life when I survived on a lean diet of functionality have been disastrous for everyone. I’m fortunate that my socio-economic background has given me education and opportunities Sula never had. By keeping at least one toe in the hot water of singing, dancing, directing, etc., I can escape my personal favorite role of martyr: You always recognize her by the swath of emotional destruction she leaves as she soldiers on alone under the weight of this world.

A friend and I have an ongoing dialogue regarding the importance of “uselessness.” Both being rather codependent worker bees, we tend to forget the necessity of art. How can you tell if it’s art or not? If it serves no practical purpose, and is utterly useless, it’s probably art.

When we let down our guard, our artistic endeavors may creep toward the useful—raising funds for worthy causes, building community, educating children (yawn). So we are ever vigilant on each other’s behalf: “My dear, I would love to support you in such a project, but it does sound awfully useful….” Grateful for the correction, we again set forth on our true artistic paths.

I once wrote a poem that accidentally recapped some key events in the life of an uncle of mine. I had some trepidation about reading it in public, so I decided to read it to him over the phone first. He was deeply touched, honored even, and asked me to send him a copy. I must have had a foretaste of the doom to come, because I delayed mailing it for a couple months. When my uncle finally did get it in the mail, he replied with a scathing rant, pronouncing my “sadistic” poem the perfect product of our family’s Germanic, authoritarian, puritanical heritage.

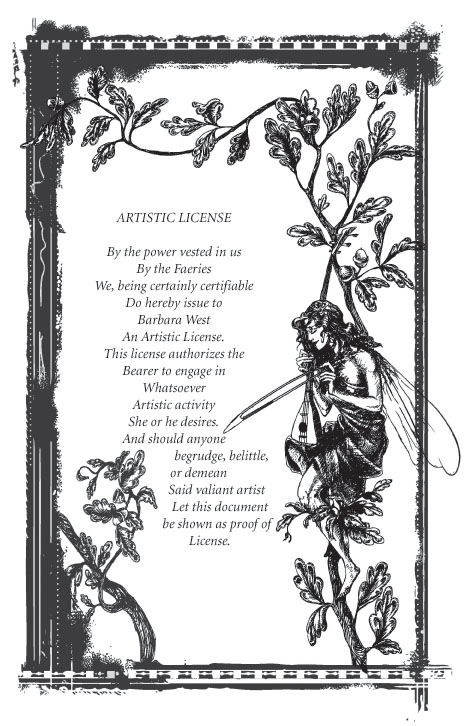

Fortunately, I already had my artistic license. This was given to me by a couple of license-dispensing faeries parked just across the sidewalk from my Waldorf School outreach booth at the Whole Earth Festival. I watched them and their happy customers all weekend, as far as my duties—helping

5-year-olds change yarn colors on their God’s Eyes—permitted. During the slow times, the faeries were doing some kind of acro-yoga on the grass, which—in addition to their wings and spandex—made them pretty interesting to watch. But I felt superior to their frivolous enterprise. I was doing something useful: promoting our school, saving the world through the education of future artists, assisting with the actual production of many works of art involving at least two sticks and three or more yarn colors.

However, as we dismantled our respective booths Sunday evening, one of the faeries called across the sidewalk asking if I too wanted a license.

I paused.

I wasn’t sure if I was an artist or not. And if I was an artist, I didn’t think I needed a license granted by a couple of acro-yoga faeries. Fortunately, my wiser self intervened and said yes. When they handed me my beautiful, customized license, I learned that they were ALIBI (Artistic License Issuing Bureau Incorporated).

This was the moment when I became an artist. And not just any artist, I was “Said Valiant Artist.” Years later, when I struggled with the painful letter from my uncle, my license (now framed on my wall) reminded me that I was authorized to “engage in whatsoever artistic activity she or he desires / And should anyone begrudge, belittle, or demean said valiant artist” this document may be shown as proof of license. My artistic life was now not only valiant, it was valid.

I know instinctively that my son’s and other children’s artistic lives are of central importance. Perhaps I learned this from the suicides of too many friends who bore the pain of being artistically gifted in nontraditional ways. Or did I learn it from the alcoholics, potheads, and cigarette smokers I still love who need chemical support to reconcile their talent with daily life? Or, the ones who’ve crucified themselves on the cross of academia, in hopes they could someday be paid to write and speak about their passion? Maybe it’s the rest of us—in 12-step groups, in and out of therapy, on and off antidepressants—as we strain to believe, at last, that it’s OK for us to take care of ourselves and to create what we find to be beautiful or true.

I know art is a necessity for my son. I know it well enough to keep paying Waldorf School tuition. I know it well enough to have kept forcing him to practice the cello five days a week (over the extended family’s pleas to “stop the torture!”) and to find him yet another teacher who offers that brilliant balance of discipline and inspiration, allowing him to play beautifully enough that, at last, he loves to hear himself. I know it’s worth it.

Knowing it for myself is much trickier. Shopping at Costco rather than buying organic at the co-op saves more than the $37 a week needed for cello lessons. The money saved from settling for $6,000-deductible health insurance allows me to contribute more toward his school tuition. But taking a week off work for the veil-painting class gets into the big-time territory of job security, retirement savings—the safety net.

Thanks to Toni Morrison’s Sula quote on my bulletin board, I know that it’s not art vs. safety after all. It’s just a matter of balancing different kinds of safety. Hmmm … rather than wait to see if that vacation week gets approved, I think it may actually be safer to submit my resignation and go back to per-diem status.

The current collapse of capitalism helps too. That retirement I might have saved for has melted away on Wall Street anyway. I realize now that I don’t need to retire at 65 and travel to Europe when I’m 72. The day I turn 72, I’ll ask for the day off work to make up a new song with my neighbors. Look for us on the sidewalk at the edge of the festival; we’ll be proudly (and safely!) displaying our artistic licenses on an open cello case.

Barbara West is the 42-year-old only parent of a 12-year-old, living with assorted housemates in a co-housing community in Davis, Calif. She keeps quitting jobs with benefits as a hospice nurse in order to make another run at sanity/safety/art.

Email This Page

Email This Page

February 24th, 2010 7:53 am

I love this piece! Hooray for the freedom to be creative. Here's yet more "permission" from artist/dance/choreographer Martha Graham….

"There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open. … No artist is pleased. [There is] no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others."'