Turbulent Origins

Democratic yearnings of Slovakia’s ‘first family’ depicted

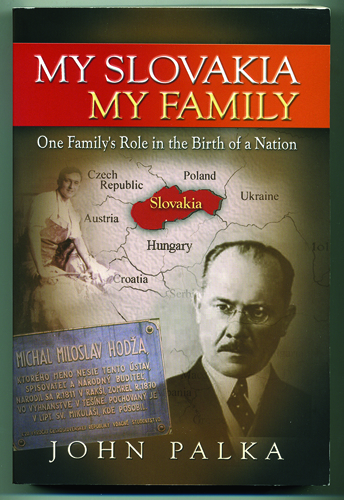

John Palka, My Slovakia, My Family. One Family’s Role in the Birth of a Nation, Kirk House Publishers, Minneapolis, 2012, 416 pp.

Minneapolis, 2012, 416 pp.

John Palka ’60 was born in Paris in summer 1939, only two weeks after his mother had escaped from the newly minted Nazi puppet state of Slovakia. A year and a half later, surrounded by Nazi occupiers in rural Normandy, young John and his parents managed to avoid deportation to a concentration camp and, with the help of the French resistance, cross from the occupied zone to Vichy France. Using forged Yugoslav passports, the family traveled from Marseilles across Spain (where John celebrated his second birthday) to Portugal. From Lisbon, now using Czechoslovak passports, they took what was allegedly Pan Am’s last regular commercial flight to New York.

Why would the Nazis have been interested in getting their hands on this Lutheran Slovak family? The short answer, as we learn from My Slovakia, My Family, is that John Palka descended from some extraordinary ancestors, the most famous of whom was his grandfather Milan Hodža (1878–1944), interwar Czechoslovakia’s last prime minister. Hodža was a larger-than-life figure in his native Slovakia. A Slovak nationalist politician, he nevertheless promoted the continued existence of Czechoslovakia in the 1930s when many Slovak nationalists sought its division. As prime minister, Hodža was powerless to prevent the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, a country he had done so much to help found in 1918 and from which he soon had to flee.

Slovakia’s first family returned home after the war but was soon targeted by the communist regime that took power in 1948. Once more, the family fled Central Europe under equally dramatic circumstances. The Palkas adapted as best they could to American exile, maintaining their links to a Slovak diaspora, ensuring that young John maintained a connection to his family’s rich and storied past. He majored in biology at Swarthmore, then taught neuroscience at the University of Washington. In 2002, nine years after the “Velvet Divorce” that created an independent Slovakia out of Czechoslovakia, the Slovak government brought the body of Milan Hodža home from its Chicago exile for a hero’s burial. Palka accompanied his grandfather’s body, spoke at the ceremonial reburial, and has since become something of a celebrity in present-day Slovakia, promoting the democratic values for which his grandfather, along with his parents and other heroic family members, had fought during the turbulent 20th century.

Palka’s family story involves riveting drama, tragedy, exile, several dangerous escapes, and in the end, a rare vindication of those who suffered. The book does far more, however, than trace the 20th-century story of his immediate family. In parts two and three, Palka examines his 18th-century ancestors’ activism in what was then Upper Hungary. Here we meet several distinguished women and men who worked tirelessly to popularize the concept of Slovak nationhood during the 1800s. Historians often speak about a 19th-century process of “constructing nations” in Europe. Activists like Palka’s ancestors saw themselves as “awakeners,” tasked with teaching largely illiterate locals about their ethnic-national identity.

Why should local people in the 19th century—in this case subjects of the Habsburg King of Hungary—have cared whether they belonged to a nation? Palka’s ancestors engaged in a challenging struggle to make the abstract idea of a “Slovak nation” real for people. Once the masses understood that they belonged to a nation, so the activists reasoned, they would work unceasingly for the benefit of their national community.

Nationalists made people care about nationhood in a 19th-century context of rising literacy and mass political mobilization. As a result, the 20th century saw the creation of several independent, self-described nation states in Europe. It also saw nationalist reasoning increasingly used to justify harsh policies against minorities, forced population “exchanges,” ethnic cleansing, and even genocide. All of these were tools to achieve ethnic nation states out of linguistically and religiously diverse communities.

At the core of its belief system ethnic nationalism places a group—the nation—ahead of the individual. Democracy, by contrast, places the choices of individuals at its center. This is the terrible paradox attached to the work of nationalist visionaries who believed that the “emancipation” of their linguistic nation would bring greater democratization to society. Sadly, contemporary Slovakia is no exception to this rule, given its World War II history of minority persecution and the harsh and unnecessary anti-minority language laws it recently adopted.

Palka’s history reminds us of the situational character of both nationalist and democratic beliefs. Under the conditions they faced in the 19th century, activists fighting for linguistic rights saw their nationalism as an expression of democratic yearnings. Once empowered, however, that same nationalism could become toxic in its implications. Few nationalists trod the narrow path chosen by a Milan Hodža, and this made him a tragic figure in 20th-century Europe. All self-styled nation states still face the challenge of placing democratic values ahead of the nationalist ones the recent past has bequeathed them.

—Pieter Judson ’78, Isaac H. Clothier Professor of History and International Relations

BOOKS

Shalom Saada Saar ’74, Poems of Love and Loss, Eman-ations Press, 2009, 72 pp. Taking a less mechanical, but still influential, self-help approach, Saar’s poetry uses immense spirituality and a deep appreciation for life that guides readers to discover love that “feeds the soul each day.”

mechanical, but still influential, self-help approach, Saar’s poetry uses immense spirituality and a deep appreciation for life that guides readers to discover love that “feeds the soul each day.”

Emily K. Abel ’64, The Inevitable Hour: A History of Caring for Dying Patients in America, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013, 240 pp. Abel paints an intricate portrait of 20th-century medicine and the historically dehumanizing experience of dying, as medical breakthroughs trended toward emphasis on finding cures for diseases rather than relief for end-of-life pain and suffering.

Elizabeth J. Coleman ’69, Let My Ears Be Open, Finishing Line Press, 2013, 25 pp. Coleman dives deep into the heart of a variety of emotion-packed topics in this collection of poems.

Stephen Davidson ’61, A New Era in U.S. Health Care: Critical Next Steps Under the Affordable Care Act, Stanford University Press, 2013, 111 pp. This eye-opening book clarifies the Affordable Care Act and offers a comprehensive look at some key issues that will determine the success of this 2010 legislation.

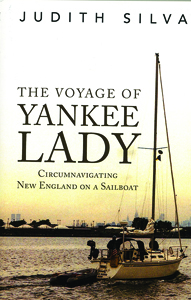

Judith Silva ’56, The Voyage of Yankee Lady: Circumnavigating New England on a Sailboat, Tate Publishing & Enterprises, 2013, 380 pp. Silva tells the story of six retired sailors who set sail on a 3,000-mile voyage along the waterways of New England. This exciting and funny book will nourish readers’ dreams of a lively, fulfilling retirement.

Judith Silva ’56, The Voyage of Yankee Lady: Circumnavigating New England on a Sailboat, Tate Publishing & Enterprises, 2013, 380 pp. Silva tells the story of six retired sailors who set sail on a 3,000-mile voyage along the waterways of New England. This exciting and funny book will nourish readers’ dreams of a lively, fulfilling retirement.

John Freeman ’96, How to Read a Novelist, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux Originals, 2013, 372 pp. Award-winning writer, book critic, and Granta editor Freeman pulls together his best profiles to share insights about novels and novelists. This is an essential read for aspiring writers and literature aficionados.

Maiah Jaskoski ’99, Military Politics and Democracy in the Andes, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013, 322 pp. With surprising results gathered from intensive research, Jaskoski’s work analyzes the Ecuadorian and Peruvian armies in an argument that uncovers these militaries’ greater concern with the uniformity of their missions rather than the sovereignty objectives they are meant to achieve.

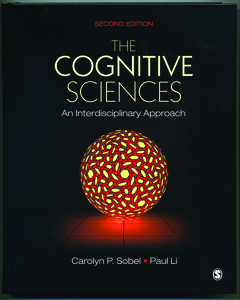

Carolyn Sobel ’60 and Paul Li, The Cognitive Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Approach, Second Edition, SAGE Publications Inc., 2013, 438 pp. Offering a look at the cognitive sciences through the lenses of cognitive psychology, linguistics, and philosophy, among other areas, the latest edition of this textbook provides readers with a broad range of background knowledge and understanding of current research in the field.

Publications Inc., 2013, 438 pp. Offering a look at the cognitive sciences through the lenses of cognitive psychology, linguistics, and philosophy, among other areas, the latest edition of this textbook provides readers with a broad range of background knowledge and understanding of current research in the field.

Justin Kramon ’02, The Preservationist, Pegasus, 2013, 282 pp. Kramon follows an unraveling relationship, told through alternating points of view, and creates a hard-to-put-down thriller.

Kirk Paluska ’90, Judy Worth, Tom Shuker, Beau Keyte, Karl Ohaus, Jim Luckman, David Verble, and Todd Nickel, Perfecting Patient Journeys: Improving Patient Safety, Quality, and Satisfaction While Building Problem-Solving Skills, Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc., 2012, 161 pp. This guide for health-care leaders describes methods of identifying and solving organizational problems without hiring consultants and while continuing to deliver quality care.

Ralph Lee Smith ’51, Smoky Mountain Memories: Beautiful Songs Collected in the Great Smoky Mountains, 1916–1918, Roots & Branches Music, 2013, 43 pp. Co-arranged with Madeline MacNeil, this compilation of traditional Appalachian songs brims with Smith’s insights into the history of the dulcimer.

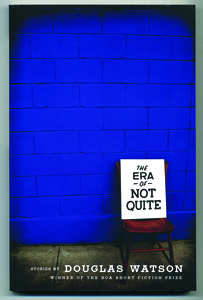

Douglas Watson ’94,The Era of Not Quite, BOA Editions, Ltd., 2013, 147 pp. Watson’s first collection of stories presents readers an intriguing and thoroughly witty perspective on a multitude of often-dark life events.

Douglas Watson ’94,The Era of Not Quite, BOA Editions, Ltd., 2013, 147 pp. Watson’s first collection of stories presents readers an intriguing and thoroughly witty perspective on a multitude of often-dark life events.

OTHER MEDIA

Jerome David Goodman ’55, Collected Music of Jerome David Goodman, Navona Records LLC, 2013. Featuring musical groups such as the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra and Prism Saxophone Quartet, this retrospective album pleases the ears, each song telling a narrative of its own.

Email This Page

Email This Page