‘Prevenient Grace’

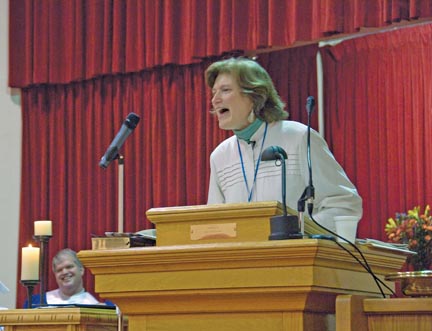

Catherine “Cathy” Good Abbott ’72 transitions from the corporate world to that of the church.

“When she became president of Columbia Gas Transmission and people asked how do you marry a chief executive, I would say, ‘It’s easy, you marry a religion major and wait 20 years,’” Ernie Abbott ’72 says of his wife, Catherine “Cathy” Good Abbott ’72, formerly an energy (and Enron) executive and now pastor at Arlington Temple United Methodist Church.

“When she became president of Columbia Gas Transmission and people asked how do you marry a chief executive, I would say, ‘It’s easy, you marry a religion major and wait 20 years,’” Ernie Abbott ’72 says of his wife, Catherine “Cathy” Good Abbott ’72, formerly an energy (and Enron) executive and now pastor at Arlington Temple United Methodist Church.

“Well, how do you marry a pastor?” Ernie continues. ‘You marry a religion major and wait 30 years.’”

Abbott brings her corporate background to Arlington Temple, a quirky church situated amid inner suburban Washington, D.C.’s, office-park sprawl, its recently-renovated sanctuary spanning a Chevron station below. (The church receives lease income from the station, maintaining a constant revenue stream that currently covers all its fixed costs.) Dressed in black but for a turquoise necklace and flowing turquoise and purple scarf one rainy April Sunday, Abbott gave a sermon on “money stress” and Jesus’s word on the matter, part of a six-week sermon series on the stresses of this world. (Did you know that 16 of 38 parables in the New Testament are about wealth or possessions or money?)

Downstairs, regular unleaded was selling for $3.65 a gallon.

At the temple two years this July, Abbott was what a friend called “a reluctant prophet,” pulled to the ministry after three decades “of not really listening to God’s will for my life,” she wrote in her 2003 statement of call. After Swarthmore, she considered seminary but opted instead to live out her faith in the world at large, first working for a nonprofit focused on peace education at Chicago churches before shifting to government service. Involved in crafting President Jimmy Carter’s energy plan as an Environmental Protection Agency analyst, she leap-frogged from there to a trade association to private industry. While working in various vice presidential positions at Enron’s Houston headquarters, her membership in the city’s St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, saved her from her own ambition, she says. “You know how Swarthmore people are. You want to do well at what you do; you want to excel at what you do. What it took to excel at Enron was kind of like going to the dark side, like Darth Vader.”

Abbott left Enron in 1995—well before it collapsed of its own internal corruption—subsequently realizing her corporate dreams when she was named president of Columbia Gas Transmission, a subsidiary of Columbia Energy. Then there was a merger and, as a self-described “servant leader,” she felt called, she says, to speak up for her people—the employees. She picked up a seminary application on a lark, the weekend before she learned that her job had been eliminated.

“In theological terms,” Abbott says, “it’s prevenient grace. It’s God moving ahead of you to prepare the way.”

Today at Arlington Temple, Abbott serves a small but diverse congregation, with 40 to 50 attendees at a typical Sunday service. Many who come are transient, in the area (or the country) for only a year or two; others are recent immigrants, looking for a church home. The sanctuary features not pews, but movie-theater–style seating, and not stained glass, but windowless walls for fear of vibrations (the church is located in Reagan National Airport’s flight path).

Called a temple to connote the idea of a “gathering space,” Arlington Temple also provides the weekly venue for a Turkish folk group to practice. A Muslim prayer group meets on Fridays, and 150 extras in a Ben Affleck and Russell Crowe movie recently congregated there for (temporary) food and shelter. In partnership with the Arlington Street People’s Assistance Network, the church feeds 20 to 25 people daily through its homeless ministry.

“I can feel the spirit coming through her,” congregation member Mashelle Pitts says of Abbott after that April service. “If you were feeling something, that was the spirit of God touching you. That’s what it was, sister.”

Email This Page

Email This Page