Faculty Retirements

Retiring, Schuldenfrei Recapitulates Readings

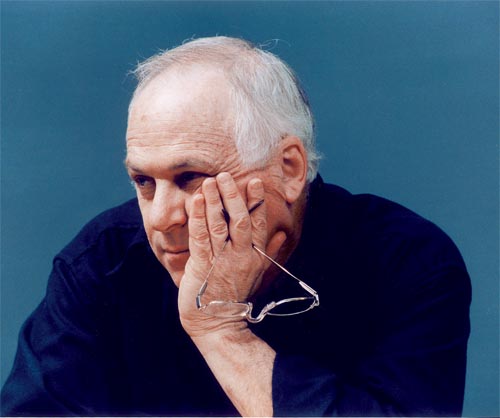

It’s September, and the students are back. Classes begin, but something vital is missing from Swarthmore’s classrooms. Professor of Philosophy Richard Schuldenfrei has retired.

I ask him, isn’t it strange not to be going back to school?

“I’m not consciously disoriented,” he says, scowling first, then smiling. “I feel great, and I’m enjoying the freedom. But I don’t know. Maybe I’m like the guy who jumps off the Empire State Building and, as he passes each floor, says to himself, ‘So far, so good.’”

Schuldenfrei, 67, whose legendary teaching verged on performance art, says he simply ran out of energy for the classroom: “I was exhausted after every class. It was time for me to stop.”

Now, he says, “I’m recapitulating my reading list”—revisiting authors who influenced or entertained him decades ago—like Isaac Bashevis Singer and Philip Roth. “I’m trying to see how I misunderstood the world when I was young, in light of how I understand it now.”

Roth’s fiction, which often explores the relationships among secular and religious Jews, might be another recapitulation for Schuldenfrei, who was raised by left-wing, nonreligious Jewish parents in Brooklyn. In the June 1998 Bulletin, Rich told writer Vicki Glembocki that when he left home for the University of Pennsylvania, the religious aspects of Judaism weren’t a part of him: “‘I was like a fish in water—I didn’t know that I was wet,’ he says of his Jewishness. Now, reflecting back, Richie thinks he may have stumbled into philosophy because he was looking for guidance that he hadn’t realized through religious study.”

Once a vocal Marxist, Schuldenfrei underwent a philosophical and political transformation during the 1980s. The atrocities committed by Pol Pot in Cambodia drove him away from the moral and political philosophy he had chosen in the 1960s. “Marxist radicalism was what my life led up to and away from,” he told Glembocki. “I’m surprised now to see what a short period that was in my life, but it was pivotal.”

“In my youth,” Schuldenfrei explains, “I was a positivist, scientistic person—informed by the Enlightenment. Marxism was a point of view, a more radical place from which to examine science as ideology. But then I came to see Marxism itself as ideology.”

Schuldenfrei’s father, raised in Poland, had, as a young man, abandoned the religious aspects of his Jewishness. He became a Marxist but later, after emigrating to the United States, adopted liberal secularism.

Schuldenfrei the son, although raised culturally Jewish (he attended Hebrew school four days a week in grade school), went further down the secular path—all the way left—then turned back, seeking the boundaries that religion imparts, the limits that help define right and wrong.

“My trajectory,” he says almost confidentially, leaning across the table, “is reflected in this interview, in which I am revealing more than is probably required by the etiquette of a retirement interview, but I don’t really know how to talk any other way.”

For 40 years, Schuldenfrei has been talking with his students the same way, often asking, “How do you live a good life?” A moral life. A life in community with others. A life that has meaning.

“I still ask this,” he says, “but I’ve narrowed the focus. I no longer have to accommodate other people’s answers to this question—students’ answers.”

Retirement seems to suit Rich. His younger daughter just graduated from high school, so the nest is emptying. (He married Helen Plotkin ’77 in 1984. They have two daughters. Plotkin is director of the College’s Beit Midrash, a center for Jewish study, and recently became an ordained rabbi.) He spends his time reading and recapitulating—“and a lot of time just sitting and thinking. Helen will come in at the end of the day and ask, ‘Did you have a nice day?’ ‘Yes,’ I’ll say. Then she’ll ask, ‘What did you do?’ ‘Nothing,’ ” I’ll reply.

Such a luxury for a philosopher.

Kurth Leaves the Faculty but not the Field

James Kurth, who formally retired in June, will continue to teach and write as an emeritus professor.

With his retirement in June, James Kurth, the Claude C. Smith Professor of Political Science, has become an emeritus member of the faculty. But that doesn’t mean that he’s quit the College or the classroom. This fall, Kurth is teaching Defense Policy and advising two students doing directed readings. He says his plans for future teaching are uncertain, but he expects to stay engaged with Swarthmore students and alumni. Kurth remains active in the Philadelphia-based Foreign Policy Research Institute and is former editor of its journal Orbis. His writing has appeared frequently in journals such as The National Interest, The American Interest, National Review, and The American Conservative. In a widely read 1994 article in The National Interest, Kurth asserted that the United States is less threatened by clashes with other civilizations than by ideological and cultural divisions within the country, especially those “between the multiculturalists and the defenders of Western civilization and the American creed.”

Kurth received a B.A. in history from Stanford and an M.A. and Ph.D. in political science from Harvard, where he taught from 1967 to 1973 before joining the Swarthmore faculty. A Navy veteran, he has served as visiting professor and chairman of the Strategy and Campaign Department of the U.S. Naval War College.

Email This Page

Email This Page