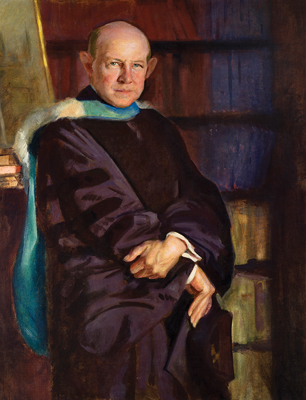

Leadership Position in the Liberal Arts Grew from One Man’s Distinctive Vision

Variously called “bold,” “generous,” “outsized,” Frank Aydelotte’s ears were often the object of good- natured joking, which Swarthmore’s seventh president enjoyed as much as anyone. But he listened intensely with those ears as his keen lifelong curiosity about the world took him far from his small-town Indiana roots. With his infectious enthusiasm, gregarious nature, and strong work ethic, the former English professor was well suited to changing the educational culture at the College when he arrived in 1921.

natured joking, which Swarthmore’s seventh president enjoyed as much as anyone. But he listened intensely with those ears as his keen lifelong curiosity about the world took him far from his small-town Indiana roots. With his infectious enthusiasm, gregarious nature, and strong work ethic, the former English professor was well suited to changing the educational culture at the College when he arrived in 1921.

Provincial Swarthmore itself was primed for change. Aydelotte’s predecessor and fellow Hoosier, Joseph Swain, had by that time assembled a strong faculty supported by a sound financial structure. Swain had also unwittingly contributed to the College’s transformation nearly 20 years earlier when, as president of Indiana University, he encouraged Aydelotte, a recent graduate: “Frank, has thee heard of these Rhodes Scholarships? Thee ought to get one of them.”

Aydelotte was delighted to receive a Rhodes in 1905, following postcollege stints as a journalist, English professor, and Harvard graduate student. His experience at Oxford, with its tutorial system emphasizing intellectual debate, independent study, and weekly essays, culminating in critical final exams, had a profound effect on Aydelotte’s views of education.

After Oxford, he taught English at his alma mater and MIT, using writing as the primary tool to make students better thinkers. Instead of conventional, separate composition and literature survey courses, Aydelotte assigned more focused reading in some of his favorite 19th-century essayists, calling upon the students to explore ideas suggested by the reading. He called it “training in thought.”

Aydelotte was eager to establish this kind of critical thinking as Swarthmore’s standard of learning. “Liberal arts,” he wrote, “is not a formula; it is a point of view. The essence of liberal education is the development of mental power and moral responsibility in each individual.”

Thus he proposed an Honors Program that was adapted from his Oxford experience. In Aydelotte’s version, the format consisted of two years of small, ungraded seminars that emphasized the overlapping nature of related fields of study and culminated in final examinations given by outside academics. The Honors Program was meant to allow those select individuals within it to rise as far as their aptitude would take them.

Beginning with English and history, the program grew more inclusive as Aydelotte shepherded it throughout his 19-year presidency. He wrote that he had no doubt that “the Quaker tradition of Swarthmore contributed more than anyone … realized to the success of honors work.”

Aydelotte’s concentrated effort to establish “a college and not a social club” was helped enormously by his considerable fundraising skills. He advocated Open Scholarships, modeled on the Rhodes, which encouraged broader student interest in the program. In the service of his academic vision, Aydelotte also changed the role of sports in the College, emphasizing participatory athletics above the traditional “spectator” sports.

The Honors Program increased Swarthmore’s visibility in the world of higher education. In addition to external examiners, many outside observers from institutions interested in developing their own honors programs visited the campus. The program also attracted more academically committed new students from a wider geographical area, even if they did not ultimately participate in honors. The “rising-tide-lifts-all-boats” principle was evident in Swarthmore’s gradual transformation from an academically average, regional college to a leader in liberal arts education. Aydelotte’s outstanding faculty hires, including a number of his fellow Rhodes scholars, also contributed to the College’s escalating reputation.

After Aydelotte’s retirement, the grateful faculty published a book detailing the history of his tenure at Swarthmore, subtitled “An Adventure in Education.” Three years later, while serving as president of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, Aydelotte wrote his own version of events and dedicated it “To the Faculty of Swarthmore College, whose book it is.”

In the nearly three-quarters of a century since Aydelotte left the College, Swarthmore’s Honors Program has evolved in response to changing circumstances. But the underlying emphasis on intellectual inquiry has remained the same.

The June 5, 1933, edition of Time magazine, which featured Aydelotte on the cover, declared: “Swarthmore has produced no Einstein. That is what Frank Aydelotte wants to do next.” Five years later, he produced the next best thing: the actual Einstein, who appeared at graduation to receive an honorary degree. A photo of the duo provides daily inspiration for Swarthmore’s current president Rebecca Chopp, as she continues the quest to enrich the world with the liberal arts way of learning.

Email This Page

Email This Page