Exploring the Great Gift of Life

Snappy dialogue, vivid portraiture enliven literary memoir by former ‘New Yorker’ editor

Daniel Menaker ’63, My Mistake: A Memoir. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, 2013, 256 pp.

Ben Franklin, who knew something about writing, editing, and publishing, quipped in his Autobiography that God was a loving proofreader who forgave and corrected the “errata” of our lives. A similar sense of wry understanding marks Daniel Menaker ’63’s recently published memoir My Mistake. Menaker worked for 26 years at “the brilliant crazy house called The New Yorker,” climbing his way up from fact-checker to copy editor to one of the people responsible for the stellar array of fiction and nonfiction the magazine published in the 1970s and 1980s. He then spent 15 years with a variety of book publishers in New York, rising to editor-in-chief at Random House, and had a firsthand glimpse of the changes made by two tsunamis that struck book publishing within the last two decades.

that God was a loving proofreader who forgave and corrected the “errata” of our lives. A similar sense of wry understanding marks Daniel Menaker ’63’s recently published memoir My Mistake. Menaker worked for 26 years at “the brilliant crazy house called The New Yorker,” climbing his way up from fact-checker to copy editor to one of the people responsible for the stellar array of fiction and nonfiction the magazine published in the 1970s and 1980s. He then spent 15 years with a variety of book publishers in New York, rising to editor-in-chief at Random House, and had a firsthand glimpse of the changes made by two tsunamis that struck book publishing within the last two decades.

The first was the wave of mass corporatization: Most publishers are now owned by multinational conglomerates, and all books are treated like commodities and expected to turn a profit. Simultaneously, the wave of digital publishing hit, causing not just many bookstores to be swept away but also the idea that all books should be edited by professionals, not commercial agents or the authors themselves. How many future Swarthmore grads will have anything like the “career” in publishing that Menaker cobbled together? Editors will still be needed, but increasingly authors will primarily deal with commercial agents and acquisition editors who must think like accountants. On all this Menaker’s memoir ruefully reflects.

My Mistake is also a very personal book, not an essay on the vagaries of the publishing industry. Spurred by a bout with cancer, Menaker stepped back from the hurly-burly to survey the odd twists and turns of his life. He still feels great guilt for being partially responsible for the death of his much admired older brother. He acknowledges his lifelong problems with authority, even as he realizes that he continually sought out father figures. And he offers the priceless sense of comedy that only hindsight can bring: some of our most self-assured decisions in life turn out to be wrong, while some of our “mistakes” eventually prove to be surprisingly beneficial. Going through photos and memorabilia of a childhood in Greenwich Village and Nyack, N.Y., Menaker realizes how blessed he’s been both with family and career: “I have never seen better days. No mistake.”

Menaker discusses his Swarthmore years with affection and humor. He takes honors in the days of eight exams—in English, art history, philosophy. Aside from giving Menaker a breadth of knowledge in the sciences and the arts, Swarthmore enhanced his skepticism of authority, broadened his taste, and honed this future writer’s eyes, ears, and sense of humor. He remembers a psychology experiment in which volunteers wore glasses that turned everything upside-down for three or four days, “to find out if upside-down will eventually become right-side-up, and how long that will take.” No wonder Steve Martin enjoyed and blurbed this memoir.

After a short stint in grad school Menaker landed at The New Yorker, where from William Maxwell in particular he learned editing and how to handle authors with the right mix of empathy and shaming. He worked with Alice Munro—2013’s winner of the Nobel Prize—editing many of her early stories. Upon moving to Random House, Menaker drew on his love of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and audaciously sought to acquire as “his” first book George Saunders’ short story collection CivilWarLand in Bad Decline. Saunders’ book no doubt was a loss leader for its publisher for many years. But now it’s frequently reprinted, and Saunders is recognized as our great satirist of the Reagan and Bush years of American decline.

Other “mistakes” for which Menaker smiles and mimes a mea culpa include Elizabeth Strout’s Pulitzer-winning novel Olive Kitteridge; Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin (National Book Award); Siddhartha Mukherjee’s inquiry into cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies; and Reza Aslan’s Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth. Not to mention working with Billy Collins, David Foster Wallace, Jennifer Egan, Antonya Nelson, Michael Chabon …

Near the end of My Mistake, Menaker rightly mentions that “memoirs by their very etymology depend not on paper and physical artifacts but on memory … No wonder we don’t trust them entirely.” Maybe My Mistake is like those experimental goggles Menaker remembers with such amusement from that Swarthmore psych experiment—except this device flips time, not space.

Make no mistake: Try on My Mistake.

—Peter Schmidt, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of English Literature

BOOKS

Dean Baker ’80 and Jared Bernstein, Getting Back to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People, The Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2013, 106 pp. The authors argue for the increased bargaining power that full employment provides and discuss a broad set of policies to boost economic growth.

Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum ’86, Carmen: A Gypsy Geography, Wesleyan University Press, 269 pp. Bennahum presents an interdisciplinary, genealogical investigation of the Gypsy female flamenco dancer throughout history.

Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum ’86, Carmen: A Gypsy Geography, Wesleyan University Press, 269 pp. Bennahum presents an interdisciplinary, genealogical investigation of the Gypsy female flamenco dancer throughout history.

Robin Chapman ’64, One Hundred White Pelicans, Tebot Back, 2013, 80 pp. Chapman’s latest book of poetry meditates on nature’s profound beauty and vulnerability. Environmental activist Bill McKibben calls the poems “redolent.”

Julie Greenberg ’79, Just Parenting: Building the World One Family at a Time, 2014, 243 pp. Greenberg recounts her journey of “alternative” family-making through writing infused with endless optimism, love, and compassion. Greenberg, who had always planned to be a mother, invites readers to relive her experiences with multiracial children, donor dads, birth parents, women lovers, and former lovers—all significant steps on Greenberg’s humbling path to parenthood. (See Page 57 for a profile of Greenberg.)

Stephen Henighan ’84 (translator), Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret, Biblioasis International, 2014, 172 pp. Set by the beaches of Luanda, this is a charming story of the power of family loyalty and friendship that The Guardian has praised as “deceptively simple but highly entertaining.” Henighan translated this book from the Portuguese as well as author Ondjaki’s previous work, Good Morning Comrades.

John P. King and William S. Jewett ’64, Robustness Development and Reliability Growth: Value-Adding Strategies for New Products and Processes, Prentice Hall, 2010, 603 pp. The authors offer a guide to engineering processes for the development of new products, with approaches that are also adaptable to the business sector.

Keetje Kuipers ’02, The Keys to the Jail, BOA Editions, 2013, 92 pp. Kuipers’ collection of poems delves into the nature of loss, blame, and failed love.

Keetje Kuipers ’02, The Keys to the Jail, BOA Editions, 2013, 92 pp. Kuipers’ collection of poems delves into the nature of loss, blame, and failed love.

Jacqueline Lapidus ’62 and Lise Menn ’62 (editors), The Widows’ Handbook: Poetic Reflections on Grief and Survival, The Kent State University Press, 2014, 335 pp. This collection of poetry and memoir reflects the thoughts, pains, revelations, and nostalgia experienced by American women of all ages—legally married or not—whose partners have died. The Widows’ Handbook is the first anthology of poems by contemporary widows. The writing is sometimes desperately heartbreaking, other times declarative and powerful—but always honest and accessible.

Richard Stone ’65 Hidden in Plain Sight: Profiles of Fresno’s Unsung Progressive Activists ,CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013, 260 pp. Community Alliance editor Mike Rhodes deems this book “a gift of immeasurable value,” with its stories—originally published in the newspaper—of the efforts of peace, social, and economic justice activists in Fresno, Calif.

Selected Essays of Erich Auerbach: Time, History, and Literature, edited and with an introduction by James Porter ’77, Princeton University Press, 2014, 284 pp. Auerbach is celebrated for his classic comparative literary study Mimesis and is recog-nized as one of the greatest literary critics of the 20th century, yet, until now, many of his essays went uncited and were unavailable in English.

Selected Essays of Erich Auerbach: Time, History, and Literature, edited and with an introduction by James Porter ’77, Princeton University Press, 2014, 284 pp. Auerbach is celebrated for his classic comparative literary study Mimesis and is recog-nized as one of the greatest literary critics of the 20th century, yet, until now, many of his essays went uncited and were unavailable in English.

Douglas Watson ’94, A Moody Fellow Finds Love and Then Dies, Outpost19, 2014, 170 pp. As its back cover proclaims, not everyone “gets to find love” before they die, and “some people don’t even get to look.” This is a story of how one man, Moody Fellow, did all of the above. The author applauds the telling of Moody’s tale as “a welcome reminder of the magical properties of fiction.”

Brenda Webster ’58, After Auschwitz: A Love Story, Wings Press, 2014, 152 pp. Webster’s fifth novel tells the story of Hannah, a child survivor of the Holocaust, and her caretaker, a famous Italian filmmaker, in an exploration of aging, memory, and enduring love.

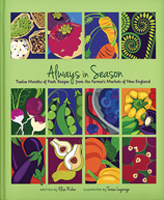

Elise Richer ’92, Always in Season: Twelve Months of Fresh Recipes from the Farmer’s Markets of New England, IslandPort Press, 2013, 192 pp. This cookbook presents more than 130 flavorful recipes that highlight the produce of the New England growing season.

England, IslandPort Press, 2013, 192 pp. This cookbook presents more than 130 flavorful recipes that highlight the produce of the New England growing season.

Douglas Worth ’62, Thumpy the Christmas Hound, Tate Publishing, 2013, 46 pp. Children and their parents will enjoy the story of Thumpy, a stray dog who stays in the Bethlehem stable, where he protects the baby Jesus from a gang of rats planning to harm him. The story shows why Christmas is celebrated: to welcome peace every year.

Linda Howard Zonana ’58, Vertigo! When the World Spins Out of Control, Outskirts Press, 2014, 209 pp. Drawing upon 50 interviews and her own experience with Menière’s disease, the author describes “vestibular” illnesses and the feeling of vertigo for the general public.

Email This Page

Email This Page