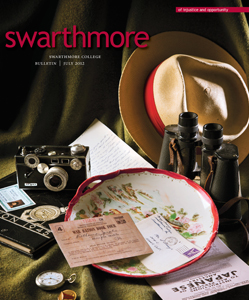

Of Injustice and Opportunity

When thousands of Japanese Americans from California and the Pacific Northwest were interned during World War II, those of college age were relocated further east. Eleven came to Swarthmore.

Photo by Laurance Kesterson

Ruth Dohi was excited. It was September 1942, and she was in a train, on her way to Swarthmore College. She was enjoying the ride—a long one, of more than two days—from Arizona to Pennsylvania. In a later letter, she wrote: “The fall leaves were quite lovely … and the countryside was most captivating and picturesque to my unaccustomed eye. … The staid but energetic atmosphere, the language, the temperament, and the people—all so very interesting and charming. I was very much thrilled to be in the East!”

Dohi’s excited anticipation is surely typical of generations of young people on the threshold of a college experience. Yet she was not typical. Dohi was one of more than 112,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei), including thousands of students, who during World War II were ordered by the United States government to evacuate their homes or campuses in the coastal areas of California and the Pacific Northwest to be interned in concentration camps further inland, away from the coast.

In the same letter, Dohi wrote of her trip: “… it was quite soothing, in effect; for once, I was a passive spectator outside of the moving scene, instead of being one of the surging multitudes embroiled in the constant churn of camp life.”

Ruth Dohi '44, one of Swarthmore's first Japanese-American students.

Dohi, who graduated in 1944 with a bachelor of arts in English literature, was able to do so only because of the efforts of a group of dedicated volunteers, many of whom were Quakers, including Swarthmore President John Nason and Frank Aydelotte from the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton and Nason’s predecessor.

In a recent, brief telephone conversation, Dohi, now 90, living in Azusa, Calif., and just released from hospital, said, “I had a very special time at Swarthmore. It was wonderful to be given the opportunity to enroll there. I owe so very much to the Quakers and the College.”

Housed in the College’s Friends Historical Library, The Aydelotte Papers detail the challenges and successes of the individuals and groups that facilitated college placement and financing for Dohi and others like her. According to statistics noted in the papers, the Japanese population of the mainland United States in 1940 numbered 126,947. Most of the first-generation Japanese immigrants, known as Issei, had been U.S. residents for more than 30 years but—born in Japan—did not have U.S. citizenship. Their children and grandchildren—second-generation young adults (Nisei) and third-generation children (Kibei), were born in the United States and were American citizens.

The Japanese-American community was made up of loyal, contributing members of U.S. society, typically farm owners, managers, laborers, and foremen as well as unpaid family farm workers. They also worked for manufacturers of food, textiles, chemicals, leather goods, printed goods, clay and glass, iron and steel, and machinery. They lived normal, industrious, peaceful lives.

Normality ended on Feb. 19, 1942, when, reacting to the Dec. 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese, President Franklin D. Roosevelt mandated—for reasons of “military necessity”—the eviction of Japanese Americans living in Pacific coastal areas and their relocation to camps inland from the Western Defense Zone.

The following month, Roosevelt created the War Relocation Authority (WRA), a civilian organization that was to provide for “the relocation, maintenance, and supervision of persons designated for removal by the Military Commander, to relocation projects.” By early June, 99,770 Japanese had been evicted from their homes and moved to hastily constructed assembly centers located in fairgrounds, parks, and racetracks. In overcrowded conditions and lacking conveniences, the evacuees were held while the Army had built 10 concentration camps in some of the hottest, driest, most inhospitable regions of Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming.

Forty years later, a presidential commission labeled the indignities perpetrated against the Japanese Americans by the government and the military a “failure of political leadership” based on “racial prejudice” and “war hysteria.”

The plight of more than 3,000 young people whose academic careers had been jeopardized by incarceration attracted much sympathy, particularly from the presidents and faculty members of many colleges and universities as well as members of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) and other religious groups.

Manzanar, at the foot of California's Sierra Navada Mountains, was one of 10 internment camps and housed 110,000 Japanese Americans. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Print and Photographs Division, Ansel Adams

In spring 1942, the academic leaders and the AFSC began strategizing to find a way to keep the students in school. Working with the WRA, they formed the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC), a 40-member group that set about creating a relocation program that would allow students whose studies had been disrupted by the evacuation to resume their schooling—mostly in Midwestern and Northeastern colleges and universities, including Swarthmore, where John Nason was president. In October 1942, the 38-year-old Nason, who had been president of the College for two years and was a Quaker and AFSC member, was appointed national chair of the NJASRC. The council’s goal was to have students back in college by fall 1942.

The relocation project was complex and expensive. Colleges, some of which housed military personnel, had to be cleared, investigated, and deemed suitable to accept Nisei students. Once accepted, the students needed FBI clearance to enroll in school as well as government passes to leave the camps. Funding for tuition, lodging, and travel costs also had to be raised.

An initial $10,000 grant was secured from the Carnegie Corporation to cover the costs of the organization and administration of the NJASRC. By September 1943, Nason was able to write in a semiannual report covering the first half of that year that a total of 3,326 Nisei were on their way to college. By the end of the war, Nason and the NJASRC had helped almost 5,000 Nisei students gain access to colleges and universities. Many of the students became Quakers as a result of the care and support they received from the NJASRC.

Thanks in part to John Nason, College president from 1940 to 1953, almost 5,000 Nisei students could attend colleges and universities. Portrait by Gordon C. Aymar.

Nason chaired the council from 1942 to 1949. In a June 1994 oral history interview, he said he believed the confinement of the Japanese-American population to have been “an outrage, unnecessary and illegal” and that he had joined the relocation effort to “correct a real social injustice.” He added, “I look upon the work I did with the NJASRC as the single most satisfying piece of work I’ve done in my career.”

Along with Ruth Dohi, at least 10 other Nisei students are known to have attended Swarthmore in the 1940s under the NJASRC relocation program. Five of them, all now in their late 80s or early 90s, were asked to share their memories of those years. The others, four of whom are known to be deceased, speak loud and strong through the voices of their children—immensely proud of their parents—and from letters, speeches, and other archived materials, carefully kept, rarely looked at, but harboring stunning revelations and testimonies to the triumph of human endurance and courage over adversity.

Given the role of goodwill ambassadors in their new college settings, the young Japanese Americans acquired a reputation for being model students and community members—industrious, academically gifted, friendly, and popular.

Here are their stories, pieced together from interviews, first-person written accounts, obituaries, archival material, and statistical reports.

A typical Japanese American family—the Inouyes

William ’44, George ’44, and Miyoko ’47 Inouye lived in Sacramento, Calif., with their parents Saburo and Michiyo. Although they are all deceased now, William’s sons, David ’71 and Robert; and George’s son Roger ’83 shared their own memories as well as copies of their parents’ writings and other documents, the original versions of which are housed in the archives of the Balch Institute of Ethnic Studies in Philadelphia.

According to an autobiographical sketch by William Inouye, his father was born in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1888, and his mother in Tokyo in 1899. Saburo moved to the United States in 1914 and was a laborer in a variety of positions. He returned to Japan in 1919, married Michiyo, and brought her back to America, where they settled in Sacramento, Calif., and opened a furniture store.

As Isei, Sabaro and Michiyo were not American citizens, but their children were. After high school, William spent a year in Tokyo, visiting his maternal grandfather and studying Japanese. Upon his return to California, he attended junior college for two years, then UC–Berkeley, majoring in biochemistry. He speaks of his mother teaching Japanese reading and writing after school and on weekends, of the tightly knit Japanese community, and of the low rate of criminal activity among the more-than 100,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast.

Then, “in May 1942, the entire West Coast population of Japanese citizens and their offspring were incarcerated in concentration camps, not charged with any crime,” William wrote.

The Inouyes were evicted from their home, taken to an assembly center and later interned first at Tule Lake relocation project in California and later at Jerome, Ark.

David Inouye describes how his father’s camera was confiscated for fear that he would use it for espionage purposes. His Uncle George had been a ham radio operator, and after Pearl Harbor, his mother destroyed his radio so that he couldn’t be accused of using it to communicate with the Japanese.

“All personal … and business goods had to be disposed of or stored,” William wrote. “Our parents’ furniture store was sold for $300—a business that had supported four families.” In the camp at Tule Lake, “each family had a small room about 15-by-20 feet long, tarpaper-covered barracks surrounded by barbed wire and towers.” Meals were eaten in a common mess hall; latrines offered little or no privacy. The camps provided schooling for precollege but not college-age students. There were doctors’ offices, and the camp inmates cultivated gardens. Physicians earned $19 a month, laborers $12.

“In September 1942, George entered Swarthmore College on a partial scholarship. I joined him in January 1943, and my sister arrived in September 1943,” William writes. “For three siblings with practically no financial resources, to be enrolled at Swarthmore College was something that would not even have been considered a dream.” George and William supplemented their scholarships by working in the College kitchen, bookstore, and post office. During breaks, they repaired furniture, moved equipment, and worked at The Ingleneuk restaurant in the Ville.

In 1944, with the Inouye children all Swarthmore undergraduates, the War Relocation Authority invited their parents to move to Philadelphia to run a hostel on Chestnut Street, initially a halfway house for the Japanese-American families flocking to the city from camps around the country to seek the AFSC’s help in finding college placement or jobs. The Inouyes took in more than 1,000 of the Japanese Americans who had lost their livelihoods during the internment years.

In 1974, Michiyo (Saburo had passed away in 1969) received the Order of the Sacred Treasure from Emperor Hirohito for her role in furthering and maintaining good relations between the United States and Japan. She was the first woman east of the Rocky Mountains to be so honored.

George Inouye ’44

George Inouye came to Swarthmore a few months earlier than his older brother William. It was not unusual after the upheaval of the internments for the oldest children of families to stay in the camps to help their parents settle in.

Roger Inouye ’83 said, “I think it was a fairly traumatic experience, especially for my grandparents’ generation. They were really in the middle of their lives at that time, and everything was taken away from them. For the Nisei, it was also traumatic, but, ironically, also a unique opportunity that they would otherwise not have had. They were teenagers or in their early 20s, and although they, too, lost everything, they had time to rebound.

“This was also clear in the letters my father sent from Swarthmore, where he writes that though he was unable to attend the University of California, he was given the opportunity to attend a wonderful college,” Roger continues. “So there was a sort of dichotomy of tragedy and opportunity. And although he didn’t exactly force me to go to Swarthmore, I believe it was because he and my uncle and aunt were so grateful for what the College did for them that the legacy our family established there was so encouraged.”

Roger stresses the reluctance of his father, uncle, and aunt (Miyoko Inouye Bassett ’47) to talk about that period in their lives, and the resulting disinclination of their children to mention the topic. While actually at Swarthmore, however, the Inouye brothers were less reticent.

From October 23, 1942, shortly after arriving at college, until June 1944, when the brothers graduated, George sent home frequent long letters and chock-filled penny postcards, detailing life on campus. And fortunately, his parents kept all their children’s correspondence. George described everything from the escalators in the Omaha railroad station and a missing reservation in Chicago during his journey east to his early-morning arrival and reception by Dean Everett Hunt in Swarthmore; from the size of his room (20 by 12 feet) in Wharton to that of the library—“bigger than Sac’to’s City Free (130,000 volumes);” from the record collection to the radio station, swimming pool, and tennis courts. He wrote of visiting Philadelphia and attending Friends socials there, invitations to the homes of Dean Hunt and President Nason, the welcoming treatment he always received from professors and students, working as a cup washer in the dining hall, a concert with the Budapest String Quartet and Hamburg shows (annual musical events).

He bemoaned the lack of rice on the College menu and was dismayed at the physical education and swimming requirements for all juniors and seniors, per Army orders (although his academic performance was stellar, he received a D in P.E.). When he lost his Parker fountain pen, he requested a new one from his parents. He assiduously kept accurate-to-the-last-cent records of his expenses and income. He also shared moments of deep introspection on the state of the world and the future of Japanese Americans in the United States, especially on the first anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

In one letter, George wondered about the fate of Japanese Americans and their role in U.S. society: “I feel that we, the Nisei, have an obligation to give American democracy another chance, to overcome racial prejudice, to work for international understanding, in spite of the discrimination we have experienced. … We have a pretty good excuse, but our leaving America would be utter condemnation of democracy in the eyes of the nations of the world.”

George graduated from Swarthmore with a B.S. in engineering and went on to earn a Ph.D. in physics at Harvard. An expert on electromagnetic measurements, he worked in the aerospace industry on projects that included the Voyager, Pioneer, and Jupiter space missions.

William Inouye ’44

William Inouye graduated Phi Beta Kappa in chemistry and mathematics. To save money for medical school, he spent five years as a chemist in an asbestos factory, where exposure to the deadly substance caused the mesothelioma that ultimately killed him in 1985.

By 1949, William and his wife, Eleanor Ward ’47, had saved the $2,800 tuition for four years of medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, where he later enjoyed an illustrious career. His excellence in teaching is still honored annually with the William Y. Inouye Award, given to especially talented teaching residents.

Already as a graduate student, William built the first coil hemodialysis machine—using screening material and cellulose tubing from a hardware store, enclosed in a standard pressure cooker. The device was used at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania for some of the earliest hemodialysis procedures. Renowned as a scientist, clinician, and educator, he worked at several hospitals in Philadelphia. He and Eleanor were active Quakers.

William’s son Bob Inouye said: “Our father was by and large reticent when it came to telling us about his past. Those must have been confusing years, laced with shame, anger, uncertainty, mistrust, and worry for citizens like my father, leaving it difficult to know what to say about that time or how to say it. I think those scars and embarrassment filtered down to my generation, too, thus fencing us off from asking our parents about their experience. So, it was a rare opening when we found he had to tell his story [in 1983] as part of a lawsuit against the asbestos company.

“It was after we three sons had left home, but I can visualize him sitting in front of a typewriter, pecking out the 11 pages he wrote. I wish I could have been there. It might have been an opportunity to talk about that taboo subject.”

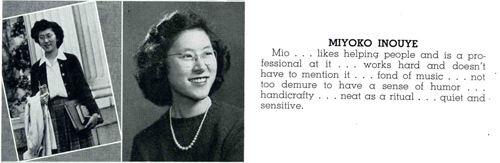

Miyoko Inouye ’47

In 2005, two years before she died, Miyoko Inouye Bassett ’47, spoke to an Asian-American history class at the University of Michigan. Her story was similar to those of many Japanese Americans during World War II, but she reached beyond her own period of adversity to empathize with those whose travails were more recent.

“In life, there may be certain profound events that you might want to suppress in order to get on with your life,” she said. “Our intern experience was one of these, which we rarely talked about, even to our children.

Few people asked about it. But there was the lingering feeling of discomfort that it had not all been put away. … The injustices seen around us made us aware that ours, too, was a major injustice, worth talking about, worth informing people, and being vigilant, and seeing that what happened to us must not happen to anyone again.

Shortly after arriving on campus, Miyoko Inoye '47 described Swarthmore as "the place of my hopes and dreams."

“After 9/11, it did start to happen again. We identified with the Muslim and Arab people who were targeted with anger and hatred,” she added. “They were falsely linked to the ‘terrorist’ just as we were linked to Japan, the country of our cultural heritage. We were as shocked as anyone with the attack on Pearl Harbor and deeply saddened also with what happened on 9/11. The anger and hostility directed to Muslims and Arabs were similar to those we experienced.”

Miyoko also speaks of acts of kindness to Japanese Americans during her time, both toward students and later toward internees released from the camps who came east in search of jobs. She mentions John Nason and the JASRC members and the 25 letters that they had to write on behalf of every student they helped enroll in college.

A junior in high school when the internment began, Miyoko came to Swarthmore in summer 1943. “Never in our wildest dream did my brothers and I believe we would go to Swarthmore College,” she said in an interview some years ago.

Like her brothers, “Miyo” excelled and, upon the advice of Professor of Biology Robert Enders, applied to Temple University Medical School. She became a pediatrician, working with her physician husband, David Bassett, whom she had met in Cambridge, Mass., when he offered to carry her baggage into the hospital where she was about to start an internship. The two became Quakers and devoted their lives to service. They worked in India on an AFSC project for two years, then spent five years in Hawaii, she as a pediatrician in a children’s hospital and he researching cardiovascular disease. Later, they settled in Ann Arbor, Mich., where they taught and mentored medical students at the University of Michigan.

TOMOMI “Tom” MURAKAMI ’44

Tom Murakami passed away on Sept. 7, but his children, Marcia ’72 and Keith Murakami, shared information about their father, whose wife, Mary Doi, also was interned but whom he met later.

“When I was a child, whenever our parents mentioned ‘camp’ and doing things like making jewelry or lampshades, I thought they were referring to Girl Scout camp or summer camp,” Marcia said. Her brother, Keith, adds, “Our parents never expressed any lingering bitterness from their treatment during the war. They tried to raise us as a typical American family. Their car-purchasing motto was always ‘buy

American.’ ”

Tom was elderly when he wrote a brief autobiography depicting his experience in the camps and afterwards.

“I missed my graduation from Compton Junior College as the ceremony was scheduled for June, and my father, my two sisters, and I were sent by bus to Santa Anita Race Track to live in the horse stables by the U.S. government at the end of May. We were assigned the front section of the stable; another family occupied the back section. We had meals at a hastily constructed wooden building.

“After about three months at Santa Anita, we were taken by train to Rohwer, a desolate place in Arkansas—in reality, a mile-square prison surrounded by a steel fence with towers and guards with machine guns every few hundred feet,” Tom added.

Tom was at Rohwer for only three months, working as a surveyor, thanks to a course he’d taken in junior college. When the installation of military units prevented him from attending his first-choice colleges, he enrolled in 1942 at Swarthmore, where all his junior-college credits were accepted, enabling him to graduate in 1944. Tuition in those days was $400 a year, which his father paid. To cover his daily expenses, he was a campus janitor and, like many Swarthmore students, a bus boy at the Ingleneuk restaurant.

The Inouye family - parents Saburo and Michoyo with children George, William, and Miyoko - form a happy family group in the Philadelphia Hostel that Mr. and Mrs. Inouye managed when they relocated to Philadelphia in 1944 from Jerome Camp in Arkansas. Photo courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Some things about life at Swarthmore were unexpected, he wrote: “All students had to pass senior life saving to get a degree. I began swimming again the first chance I got. I found the V-12 (Navy unit) was also coming to Swarthmore, but since I was already enrolled, they couldn’t turn me out.”

Tom became friends with Professor Charles Justus “Jus” Garrahan, his electrical-engineering teacher, and his family, helping with home repairs.

He later taught math and other courses at Swarthmore, during which time RCA offered him a fellowship and the equipment to solve a problem they couldn’t figure out. He succeeded, inventing a circuit that became a standard component of all FM tuners and the first of Tom’s 11 patents. He received $25 for the circuit, the going rate for patents back then, and the offer of a job from RCA, where he worked for many years.

Bernice Abe Tajima ’45

Bernice Abe Tajima, currently a resident of Honolulu but originally from Hilo, Hawaii, was at UC–Berkeley before her evacuation to Gila River, Ariz. Shortly after celebrating her 89th birthday in March, she was delighted to talk about what she could remember about Swarthmore, where she relocated in 1943.

“The president of Berkeley helped me transfer to Swarthmore, so I wouldn’t have to be interned. It was a wonderful time. Everyone was helpful and friendly. President Nason asked me to help take care of his children, so I was invited to stay in his house—even though he already had a nanny for them. During holidays, when the College was closed, other students invited me to go home with them. For a while, I also worked at a settlement house.

“People were so generous to me at Swarthmore and made sure I didn’t have to worry about anything. As I talk now about that time, all I can do is smile,” she said, with a voice that reflected her words.

Graduating from Swarthmore with a degree in economics, Bernice went on to obtain an M.S.W. from Case Western Reserve University, after which she served as a social worker at a community mental health center until she retired.

Despite the injustices they suffered at the hands of a misguided and overly fearful government, the Japanese-American students did not respond with anger and resentment. Instead, they focused on the kindness and the tireless efforts of the NJASRC and those who had helped them; they acted according to the Japanese concept that one should return a favor with an act of gratitude. In 1980 Nisei, who had attended college during World War II, started the Nisei Student Relocation Commemorative Fund as a tribute to the council of devoted Friends and others who had supported them during one of the darkest periods of their lives. The fund’s goal was to help young Southeast-Asian refugee students. In 1982, they presented their first grant—to the AFSC, in recognition of its role in the Japanese-American relocation program.

As Bonnie Gregory Inouye ’69, David Inouye’s wife, said, the Nisei of that era “were very strong inside.”

Email This Page

Email This Page