Means and Ends

When the state engages in violence, there’s a connection between capital punishment and torture.

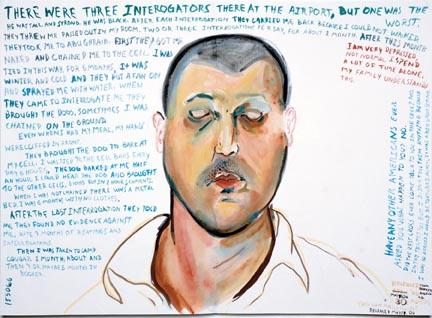

“There Were Three Interogators” (gouache on paper) is one panel in a 34-foot–long folding book by Daniel Heyman, who teaches printmaking part time at the College. Heyman’s installation The Abu Ghraib Detainee Interview Project was exhibited at The Print Center in Philadelphia in 2007.

When E.M. Forster famously wrote his “Only connect … ” epigraph to Howard’s End, he was exhorting his readers to connect the prose and the passion of life, to live life fully with others. Sociologists might also be said to live under the “Only connect…” dictum, but they derive a different meaning from it. The task of the sociologist is to demonstrate connections where others see none—to connect apparently disparate aspects of social life under a larger, overarching frame in order to reveal a larger truth. Early this year, when I prepared to participate in a workshop on the current state of capital punishment in the United States, the first thing I thought about was torture.

Capital punishment has been scrutinized in recent years on many fronts. In the United States, Illinois announced a moratorium on executions because DNA testing has revealed significant errors in convictions, and New Jersey abolished the death penalty altogether. International conventions such as the European Convention on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and United Nations resolutions, have prohibited or placed moratoria on the death penalty. And in January, capital punishment in the United States was temporarily suspended so that the Supreme Court could hear Baze v. Rees, an Eighth-Amendment challenge regarding the mechanics of execution. The question was whether lethal injection as practiced by the state of Kentucky constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment.”

In Baze, the testimony turned on the likelihood and degree of pain involved in the complex administration of the three drugs used in the executions carried out in that state. How “cruel” and how “unusual” might be the sequential, combined use of sodium thiopental (a barbiturate), pancuronium bromide (a paralytic), and potassium chloride (which causes cardiac arrest)? The case twisted and turned on the process of calculating risks of possible pain should the barbiturate not work to induce unconsciousness or if the paralytic then prevented the condemned individual from indicating his or her pain to witnesses.

The Court ruled in April that Kentucky’s three-drug protocol does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy and Samuel Alito wrote one of the several concurring opinions in which degrees of risk of degrees of pain are calibrated along a continuum from “some” to “wanton and unnecessary”—with everything from “least risk,” to “quantum of risk,” to “unnecessary risk” to “untoward risk” in between. They wrote: “To constitute a cruel and unusual punishment, an execution must present a ‘substantial’ or ‘objectively intolerable’ risk of serious harm. A State’s refusal to adopt proffered alternative procedures may violate the 8th Amendment only where alternative procedure is feasible, readily implemented, and in fact significantly reduces a substantial risk of severe pain.”

Only Justice Antonin Scalia, in a separate concurring opinion, went so far as to suggest that some pain is not only inevitable but necessary for carrying out capital punishment: “because a criminal penalty lacks a retributive purpose unless it inflicts pain commensurate with the pain that the criminal has caused.” Nevertheless, a considerable tension is evident across the seven separate opinions presented in Baze—a tension over the nature, degree, and function of pain inflicted by the state when it puts someone to death.

Meanwhile, a seemingly different debate has concurrently opened up in the United States about the viability and legality of torture. This surprising and sometimes shocking debate is linked to the promulgation of the “war on terror” and has been carried out in all three branches of government. It has focused primarily on methods of interrogation of detainees at military prisons in such places as Guantanamo, Afghanistan, and Iraq, and it has highlighted a technique termed “waterboarding,” or simulated drowning. It took the form of Justice

Department memos, Senate committee hearings, executive branch signing statements and vetoes, Supreme Court decisions, and intelligence agency revelations about missing videos of interrogation.

Most of the torture debate revolves around a few basic questions: What is torture? What is the relationship between torture and punishment? Does the United States engage in torture? Has the United States recently engaged in torture? Should the United States engage in torture? The very posing of these questions is striking. With so many national and international proscriptions against torture, one might believe the subject to be obvious and closed. (The subject may have been thought closed but not the practice. Sociologist Christopher Einolf claims that despite its formal abolition, “the practice of torture actually increased in the 20th century over the 19th.”)

Nevertheless, the current situation is one in which a deeply troubling exegesis has moved to center stage. The mere fact that there is equivocation on the reasonableness of using such techniques as waterboarding on prisoners of war—even undeclared wars and “unlawful combatants”—shocks many.

Significantly, these torture debates mirror the troubling distillation of the questions of “how cruel” and “how painful” specific state execution methods should be. As a sociologist following the foundational work of Max Weber, I ask: What amount of pain and torture is the state willing to inflict when it activates the monopoly violence that is its signature legitimate means? Even if we accept Weber’s analysis that the state successfully claims the monopoly of legitimate violence over a given territory, we must still worry and argue about the types and times of violent acts taken by the state.

My focus on means and methods might appear to be subsidiary to a more essential focus on morality or ends. Certainly, many public commentators and concerned citizens are horrified by the wayward stance of the United States on both capital punishment—for example, in 2007, the United States voted against a nonbinding United Nations resolution favoring a worldwide moratorium on capital punishment—and harsh interrogation practices that include such things as waterboarding. Such positions seem antithetical to the very identity of the United States as a harbinger of human rights and human dignity.

But when the means are violent, public consideration of means is also critical. In this regard, it is particularly noteworthy that the Baze decision contains, with Justice John Paul Stevens’ concurring opinion, a clear trajectory from means to ends. Stevens begins his opinion with an air of resignation: “When we granted certiorari in this case, I assumed that our decision would bring the debate about lethal injection as a method of execution to a close. It now seems clear that it will not…. I am now convinced that this case will generate debate … about the justification for the death penalty itself.”

Stevens moves from considering the potential pain in lethal injections to reconsidering all persisting challenges to the morality or social utility of the death penalty—the racially discriminatory way it has been meted out, its unconvincing deterrent effect, its proven susceptibility to error, and its enormous social costs—to finally asserting his definitive opposition to capital punishment.

Similarly, the focus on waterboarding—another violent means—has led to a wider conversation about a need to live up to a national self-image as respecter of human rights and dignity. It takes a greatness and complexity of vision to identify and reject cruel and unusual punishment and torture in all of its aspects and arenas. By whatever means, from waterboarding to capital punishment, both “unlawful alien detainees” and convicted capital offenders may suffer cruel and unusual punishment and pain.

These different practices of state violence ought not to be counterposed and placed in competition with each other for public attention and scrutiny. The United States may be at a critical juncture in its tolerance of state violence and torture in the name of the state. It is the obligation of the public to be vigilant in its identification of such actions and conditions and in making the connections across domains and issues, so that we can do justice to the complexity and greatness of an alternative vision.

Robin Wagner-Pacifici is the Gil and Frank Mustin Professor of Sociology. Her most recent book The Art of Surrender: Decomposing Sovereignty at Conflict’s End (University of Chicago Press, 2005) carries forward her research on the thresholds of violent conflicts. This essay on capital punishment and torture draws from a larger project analyzing the sources and nature of current debates about state violence in its many forms.

Email This Page

Email This Page