The (Really) Big Picture

Giovanna Di Chiro stresses connections between personal choice and the well-being of the planet

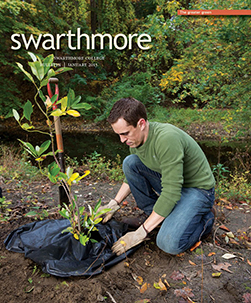

Giovanna Di Chiro requires her students to participate in outreach projects that take some of what they learn in her class back to the community. Photo by Laurence Kesterson

Draped in brightly colored saris, Indian women lean over troughs of acid, submerging discarded circuit boards shipped from the United States and other developed countries. Without protective gear, these women, and sometimes children, work day after day dipping the boards into vats of acid-based solution that removes silver and gold components from the e-waste. This is one image that Giovanna Di Chiro, Lang Visiting Professor for Issues of Social Change, showed her environmental justice class this fall semester. Student reactions were mixed.

“Some students react with shock and become mobilized to learn more about the global e-waste trade, and some are rejecting it,” says Di Chiro. “They’re either not believing [the images] or they’re shutting them out. Some maintained that sacrifices have to be made for advanced technology. But who’s making those sacrifices? If we take for granted that for all the benefits of modernity there are risks, then we have to ask: Who’s bearing the weight of those risks?”

Di Chiro, soft-spoken and good-humored, is not at all doom and gloom. Instead, the former marine biologist calmly emphasizes the need for people to acknowledge just how connected our actions are to the environment.

“I want students to think about waste,” she says. “I want them to want to find out how things are produced and where they’re going afterwards. To be genuinely sustainable we need to be able to see our everyday life as a part of a cycle.”

A longtime teacher, researcher, and activist, Di Chiro’s goals for her year at Swarthmore include a seminar in the spring (Race, Gender, and Environment) and a series of conversations on campus and throughout the region about “interdisciplinary approaches to environmental problem solving” through workshops, lectures, and outreach.

Di Chiro’s fascination with the interconnectedness of humans to the environment began in the ’80s while she was helping to develop a seaweed aquaculture cottage industry in the Puget Sound. While researching and creating this network of sustainable aqua farms, she met with community members.

“My interest in the science part of things began to intersect with the stories about people’s relationships with their environment,” Di Chiro explains.

When she returned to the University of Michigan to complete a master of science degree, she began working with low-income families in Detroit on environmental projects like cleaning up waterfronts, transforming blighted lots into community gardens, and monitoring water quality.

A physician’s daughter, Di Chiro had by this point abandoned her premed ambitions, having detected a disconnect between politics and science. Asking big questions of fellow scientists about society’s role in medicine and vice versa seemed frowned upon, she says. When her path as a biology graduate student led her to environmental justice, her scientific training and her passion for social justice and public health finally meshed.

“The intersections of civil rights, women’s rights, environmental issues, and social justice issues started to come together in the environmental community. That’s where a lot of my academic and activist focus went,” says Di Chiro.

Around the time she started working toward a Ph.D. at the University of California, residents of environmentally blighted areas began to speak out across the nation. Di Chiro’s Ph.D. and subsequent work has primarily examined how low-income communities are disproportionately overburdened with industrial waste from landfills, incinerators, and power plants.

In Di Chiro’s Environmental Justice: Theory and Action seminar in late October, 20 students discussed that week’s reading on hydraulic fracturing—tapping shale deposits for natural gas—and its implications for the land and citizens surrounding the drilling sites. The class watched a segment of the documentary Gasland, then listened as Di Chiro delved deeper into related issues of water systems, cancer statistics, and even paleontology.

Di Chiro required the class to do more than just wax philosophical on environmental matters. Thirty percent of her students’ grades depended on a group action research project with an environmental justice slant. One group researched the production-to-disposal lifecycle of the iPhone and planned to educate people about the effects of cell phones and provide options for more sustainable disposal and recycling alternatives by designing an app. Another group worked with residents of a Chester housing complex to help them feel more invested in a community garden.

“One of the major goals of the project was for students to use the information they learned and researched to raise awareness and educate [community members],” says Di Chiro.

“Figuring out how to get young people to see themselves as participating in future discussions about climate and the environment is so important,” she reflects. “I think that there is movement in that area, but will it be fast enough?”

Email This Page

Email This Page