Citizen Scientist

Alison Young ’00 trains average Joes and Josephines to examine their own backyards

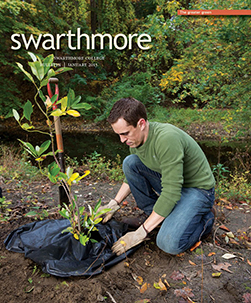

Alison Young ’00 (right) leads a team of volunteers at Pillar Point Reef in California.

“If you’d asked me when I was in grad school if I wanted to do citizen science, I wouldn’t even have known what you were talking about,” declares Alison Young ’00.

The term citizen science, she explains, means public participation in collecting or analyzing scientific research data. She describes it as “a wonderful combination of education and research,” a very collaborative, open process.” Though the phrase is new, the activity has existed for a long time. Young notes that the Audubon Christmas bird count is a type of citizen science that began more than a century ago.

In 2011, she became the first coordinator of citizen science at the venerable California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, an appointment that reflects the emerging recognition of the field. The academy is a versatile natural-history museum (including an aquarium, rainforest, and planetarium) and a busy research center. The institution’s citizen-science initiative focuses on California biodiversity.

Two sites have served as test cases for comparing current local plant and animal life to the academy’s comprehensive collection of 26 million specimens. At nearby landmark Mount Tamalpais, Young leads volunteers in a large-scale plant inventory; south of the city at Pillar Point Reef, she is in charge of an invertebrate survey at the area exposed by the tide, called the intertidal. Enhanced by georeferenced photos, the data collection thus far has been much larger than would be possible for an ordinary scientific team.

Young’s earliest scientific field trips were spent exploring the Crum Woods in the introductory biology course at Swarthmore. Her undergraduate research at the New Jersey coast on mussels made her realize that marine biology was her first love; she notes that she carried that work from one coast to the other when mussels became central to her master’s thesis at Humboldt State in northern California. Her graduate-school experience also underscored her appreciation for the College as she recognized the exceptional opportunities for genuine scientific research available to students at Swarthmore.

After college, Young taught fifth- and sixth-graders, exploring coastal habitats at outdoor-education schools in several locations. After finishing graduate school in 2009, she was an educator for the Farallones Marine Sanctuary Association in the Bay Area, overseeing coastal monitoring with secondary-school and college students. The data they mined had real-life implications. The experience, Young recounts, “opened my eyes to this whole involving-the-public-in-research [concept]—it was perfect for me!”

Young now designs future citizen-science projects, including one within the city of San Francisco. Using the academy’s historic specimens as a baseline, visitors would be able to examine their own backyard biodiversity—sites not normally available to researchers. The ultimate goal, says Young, is to have multiple projects to which anyone, museum-goer or not, can contribute.

Citizen-science investigations are everywhere, she notes. The academy is starting to network projects that include analyzing water quality, bird migration, pollinators, and even classifying galaxy shapes.

“Whatever your interest is,” Young says, “there’s probably a citizen-science project that you can participate in.”

Email This Page

Email This Page