You Born Dis One!

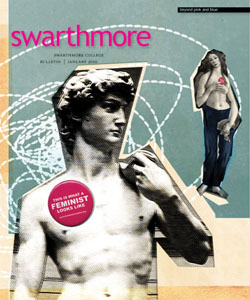

While working with the Global Action Foundation in Sierra Leone, senior Lois Park (above) initiated a children’s wellness program. She also helped to deliver a “pikin” at a local maternity clinic, assisting a nurse’s aide whose battery-powered headlamp provided the only light in a small, dark room.

On Monday afternoon, I helped deliver a baby boy. The woman in labor, Fatmata, was 23. This was her second child. A nurse aide trained in midwifery was directing the delivery. I thought I was just observing until she said, “Ah, so you are going to receive the baby for me today!” and handed me a pair of examination gloves.

“I, uhh, don’t know anything about delivering babies!” I said, half-panicked.

“When the head comes out, you turn it like this and pull it down and then up, like this!” She put her hands on my ears, pulled down, rotated a little, then pulled up. The point, she said, is to guide the shoulders out. I told her politely that I’d just watch.

We entered the delivery room—small; cramped; and smelling of sweat, bodily fluids, and old medical equipment “cleaned” to be used in this birth. The room was dimly lit by the sunlight coming through the window of an adjacent room. No electricity means no light, so the nurse aide used a battery-powered LED headlamp to do her work.

In the adjacent room were four women: Fatmata’s mother, her sister-in-law, mother-in-law, and the TBA—traditional birth attendant of their village. The incompetency of TBAs is commonly cited as an aggravator of maternal death statistics in the country, but families often choose to have TBAs assist at births because of the high fees charged by hospitals or clinics.

Two hours into labor, Fatmata had barely made any noises—some squeaks, complaints of pain, and a few quiet moans during contractions, but no screaming, no crying. Two senior nurses working at the district hospital joined us at that time. Making their rounds monitoring phase two of the polio campaign, they decided to observe the delivery.

During the third and fourth hours of labor, the aide drained Fatmata’s bladder, took her blood pressure, timed the contractions and the fetal heart rate (with an extremely crude-looking instrument which she called the ‘fetal stethoscope’), and administered an oxytocin drip, among other things. I went in and out of the room, half because I wanted fresh air, half to look at the patient’s chart. OK, mostly because I wanted fresh air.

The women waiting outside asked me if I had “born” any pikin. They looked surprised when I said I hadn’t. Then there was a change in pace of the sounds from the room. Fatmata’s water had broken.

A little more than half an hour later, the baby started crowning. It seemed like forever before the head came out. Then, after some difficulty rotating the baby so that it could be positioned for the shoulders to come out, it sort of turned itself. Then it stayed there. With its head peeking out into the world, the baby didn’t want the rest of its body to come out—or maybe Fatmata was tired of pushing. The aide tried to guide the baby’s shoulders out with her fingers—unsuccessfully. Looking at the size of the baby’s head, the nurses commented in the back of the room how big the baby was.

The baby’s mouth started twitching. “The baby wants to breathe! You Have To Push!” the aide told Fatmata. Tension in the room escalated. The senior nurses rushed to put on gloves and join in the delivery.

My stomach is in knots. I want to cry, but I find myself joining in the “Come on! Push! Baby’s almost here!” I see a little bit of blood—something in Fatmata must have ripped. I remember Sierra Leone’s maternal death statistic: One in every eight. But she’s young—23, for God’s sake! There are two senior nurses overseeing the delivery with the aide; the TBA is helping out; they brought Fatmata here as soon as she went into labor; she’s received pre-natal care, already worked so hard. She just can’t die.

A mother and child visit the clinic where Park was working in Sierra Leone.

I am yelling words Fatmata probably can’t understand. I see a shoulder, then another, and the rest of the baby comes rushing out with all the accompanying fluid and stuff.

It’s a boy.

The aide clamps the umbilical cord and cuts it. One nurse focuses on clearing the baby’s nose and mouth of fluid, the other takes care of the mother, and the aide helps her. The delivery is over, but something still isn’t right—isn’t the baby supposed to cry? I hate this eerie quiet—it’s not supposed to be like this, is it?

A senior nurse asks me to carry the baby to the adjacent room. I wrap him in a lappa and carry him out of the birthing room. His face has a bluish tint—not the nice red color of oxygen-carrying hemes. The nurse massages him with gentle but fast-moving fingers. I take over while she clears more fluid from his mouth and nose. She grabs his feet, turns him upside down and beats his feet a good few times, alternating that with furious backrubs. “Come on! Breathe, little guy.” I’m super-scared, my eyes are watery, my nose running. After more massage and more fluid extraction, the nurse pinches his nose, and that does the trick. As if he’s super-annoyed, he gives a weak cry. Like he’s eaten a drop of red food coloring, a pale pink flush creeps across his body.

The aide says, “You will tie the cord, ya?”

“I have no idea what it means to tie the cord!” I answer. She cuts a piece of string of the kind they use on cooking shows to hold big rolls of meat together while roasting.

‘Tying the cord’ doesn’t require much expertise. “Tie it tightly so he don’ bleed” the aide says, as I do another extra-tight triple tie right below the clamp, which she then releases. “We will keep like this until the rest falls off with time.” In the lobby of the clinic, she brings out a scale, balances it, and I confirm the reading: 4.8 whopping kilograms [about 10.5 pounds]. That’s one big child.

I bring the baby to where his mother is resting. “Fatmata, dis na you boy pikin! Na you born dis one!” I say. Trying to be baby-friendly, I lay the boy next to her breast and encourage her to suckle.

I don’t know what the future holds for Fatmata and her boy. But for now, I am thankful that both are alive and well.

Funded by the Lang Opportunity Scholarship Program and Swarthmore’s Public Policy Program, Lois Park spent the last two summers partnering with the Global Action Foundation and Project Peanut Butter on community-based management of malnutrition in Sierra Leone. She initiated the Pikin Welbodi (children’s wellness) Program there.

Email This Page

Email This Page