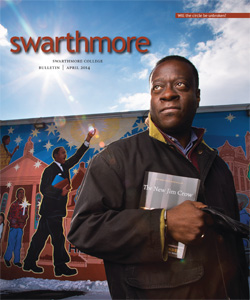

‘Where Happiness Dwells’

Sophomore-year discovery led to life among British Columbia’s Dane-zaa First Nations

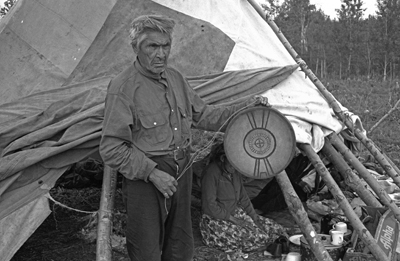

Charlie Yahey, the Dane-zaa’s last visionary, with a dreamer’s drum.

During my sophomore year, former Dean Everett Hunt gave a Collection talk. While praising what was special about the College, he mentioned two former students, Eric Freedman ’59 and Johanna “Jimmi” Mead ’58, who had left before graduating to plan their move to a remote wilderness location. I met them that winter and agreed to join them the following summer, once they had found a suitable place. Eric and Jimmi were pacifists and liked the name of the Peace River in British Columbia (BC), several thousand miles from Pennsylvania. They had no idea that they would be moving to Dane-zaa Nunne, the traditional territory of the Dane-zaa First Nations (also known as Beaver Indians). They ended up informally occupying a beautiful spot in the Minnaker River valley, 7 miles by trail from Mile 210 on the Alaska Highway.

Some months later, Bob Gelardin ’61 and I drove across the continent and hid my little Renault in the bush at the beginning of the trail. We were disappointed to find a rusty axe, some traps and blazes with names written in pencil on the trees near a small campsite. One of the names was Chipesia. I thought it sounded Italian, and my mind flashed back to kids from the city who sometimes defaced trees along the Appalachian Trail. We set out and in a few hours found Eric and Jimmi working on their cabin. A few weeks later, a group of men and boys on horseback visited. It was the first time I had met what I then thought of as “real-life Indians.” One of the men was Johnny Chipesia.

The horsemen were friendly; they asked how we were doing and what we had to eat. We proudly showed them heavy loaves of bread from grain we had ground, peanut butter, jam, and canned sardines. As we talked with Johnny and Sam St. Pierre, several boys rode across the river. Soon we heard the ping of a .22-caliber rifle, and not long after, they returned with a deer. The Indians made tea in old lard pails and set up green willow stakes by the fire to roast some ribs. We ate meat from the land with them there for the first time. They invited us to visit them on their nearby reserve at Prophet River. The day they rode into our camp changed my life. These “Indians” were Dane-zaa, and they were telling us that we were on their traditional land. They told us this, not by asking us to leave, but by feeding us from it.

That summer, I visited the reserve and got to know more people. When I returned to Swarthmore in the fall, I wanted to study anthropology. The College didn’t yet offer courses, so once a week I took a night-school introductory anthropology course at the University of Pennsylvania. The next year I talked my way into a graduate seminar on hunting and gathering peoples with the legendary Carlton Coon. I did library research on the Dane-zaa and discovered that nobody had written about the Dane-zaa of BC and that the only book about their relatives in Alberta dated from 1916. I wrote a paper for Coon, and he was happy to discover that the Dane-zaa were alive, well, and still living by hunting, fishing, and trapping. He suggested Harvard for graduate school. I told him that Harvard got so many applicants from Swarthmore that it was pretty hard to get in. “Not from anthropology,” he said and added, “A cat can look at a king. I’ll write you a really good reference.”

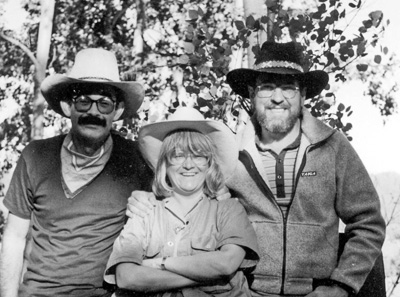

The Ridingtons began their fieldwork with their friend, the late Howard Broomfield (left) in 1978. Jillian is in the center, Robin on the right.

In 1962 I entered the Ph.D. program at Harvard’s Peabody Museum. It was tough going at first. I learned to keep my mouth shut and listen carefully, something that stood me in good stead when, two years later, I returned to Prophet River with my former wife, Antonia Mills, to begin fieldwork for my dissertation.

Another life-changing event happened that summer. Johnny Chipesia’s 80-year-old father, Japasa “Chikadee,” had suffered several heart attacks but wanted to be with his people, who lived in a hunting camp near Mile 176 on the highway. One evening he called us to his tent and began to sing and tell stories. Johnny told me that his father knew his time was near. He was telling his people about his vision quest (shin kaa) experiences when he was a child. In his songs, he called his animal helpers to him, and when he felt their presence, he told them he would not need them any more. A week later he suffered a final heart attack and died in camp surrounded by his relatives.

My research plan had been to administer Thematic Apperception Tests (TAT) to measure what social psychologists then called Need for Achievement. The people were reluctant to tell stories about pictures of white people about whom they had no knowledge. Their responses or lack thereof were discouraging. Finally, one of my subjects said, “Why don’t you listen to Indian stories?” After Japasa’s passing I threw away the TAT cards and began listening. I also began recording songs and stories on a portable tape recorder. In 1965–66 I spent a year with the Dane-zaa and met a remarkable man, Charlie Yahey, their last Naachin or dreamer (a visionary). He asked me to record him so that in later years, “The world will listen to my voice.”

The Dane-zaa have continued to be part of my life. Jillian Ridington and I married in 1976 and began fieldwork together in 1978. We continued recording stories and working with elders and people our own age. We still work with elders, but they are now our contemporaries. The Dane-zaa are unusual among Canadian First Nations in having escaped the devastation of having their children taken away to abusive residential schools. People our age grew up speaking the Beaver language and stayed close to their parents and grandparents.

We have seen many changes. Horses and wagons have been replaced by pickups, and the reserves now have running water, electricity, and even high-speed Internet. Dane-zaa Nunne sits on vast oil and gas reserves, and the people have started businesses that serve the industry. In 2005 the chief and council of the Doig River First Nation grew concerned that many of their stories and oral history would be lost as younger people grew up not speaking Beaver. By that time we had published several books about the Dane-zaa, including Trail to Heaven, which describes my early experience going from Swarthmore to the Dane-zaa. The band asked us to work with elders and use our archive of audio and video recordings as the basis of a history of the Dane-zaa First Nations. When we asked for suggestions on a book title, former Chief Gerry Attachie immediately said, Where Happiness Dwells, the English translation of Suu Na chii ge chii ge, a traditional summer gathering place and former reserve land they had lost in 1945.

Dane-zaa oral history is remarkable. Some of the stories we recorded describe people and events from the 18th century, well before Alexander Mackenzie first met them in 1793. Others give detailed and evocative accounts of the Dane-zaa experience during the early years of the fur trade and during World War I, when the Spanish flu decimated the tribe. Central to their tradition are stories of their prophets or dreamers. I was blessed to have known and recorded Charlie Yahey, the last one. Where Happiness Dwells, which was published in July, was a collaborative project. It came together because of storytellers—from Charlie Yahey, Johnny Chipesia, and Albert Askoty to our contemporaries—songkeeper Tommy Attachie, elders May Apsassin and Madeline Succona, and translator Billy Attachie.

The elders as well as today’s chief and council had faith that we would present their history in a way that would be accessible to present and future generations. We trust that long after the oil and gas deposits have been depleted, the Dane-zaa will still live in Dane-zaa Nunne and continue to know and tell the wise stories of their elders.

Robin Ridington ’62 is professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of British Columbia. Where Happiness Dwells recently won the K.D. Srivastava Prize for Excellence in Publishing, awarded annually by the University of British Columbia Press. He lives on Galiano Island, British Columbia.

Click here to see A Tree For My People, a 4-minute video by Robin Ridington.

Email This Page

Email This Page