Cori the Explorer

Cori Lathan ’88 explores at the frontier of modern technology.

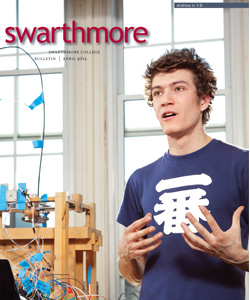

Cori Lathan ’88 demonstrates the AcceleGlove, which allows military personnel in the field to communicate with off-site software using silent hand gestures.

Last spring, Corinna “Cori” Lathan ’88 found herself breathing in the crisp 15-degree air of northwest Greenland. She had just arrived at Thule Air Force Base, a U.S. Army outpost about 950 miles from the North Pole, where she’d be spending a day testing the prototype of a new neurobehavioral assessment software she and her colleagues had designed—a tool that allows medics to track indications of neurological impairment in soldiers, from traumatic brain injury to post-traumatic stress disorder. But first she wanted to get out and explore the icy arctic landscape.

“Beautiful hike along the Greenland coast,” she wrote on her Twitter feed. “Saw two huge arctic hares romping.”

Lathan—who dubs herself an “entrepreneur, engineer, designer, roboticist”—is perhaps best described as an “explorer.” Whether navigating the new horizons of human performance engineering or observing the fauna of the frigid northern frontier, she’s driven by an innate curiosity about almost everything.

What had led Lathan to Greenland was AnthroTronix, the research and development firm in Silver Spring, Md., of which she is founder and CEO. She collaborates with a staff of 12 to build human interface technologies that empower people to overcome physical or cognitive disadvantages. Her work ranges from the cartoon-looking CosmoBot that leads children through goal-oriented activities to the snug-fitting AcceleGlove that allows military personnel in the field to communicate with off-site software using silent hand gestures. Toss in some research on how astronauts’ perception of three-dimensional space is affected by the conditions of outer space and inventing a piece of equipment that allows amputees to regain their critical sense of balance, and you start to get a sense of how exploration plays into Lathan’s daily routine.

Given the cutting-edge nature of her work, it’s no surprise that when the media spotlight shines on Lathan—which it often does—she’s revealed as one of nation’s leading innovative thinkers. Forbes, Time and The New Yorker have all featured her, and MIT’s Technology Review magazine has dubbed her one of the world’s top 100 innovators.

But, she says, “‘innovation’ is such a buzzword these days” that it’s important we don’t lose track of what it really means. In March, when she delivered a talk at TEDxSwarthmore, she aimed to give more texture to the term.

“To me, innovation is creative problem solving,” she says. “So then the question becomes, what are problems that matter? How do you find problems that matter? What do you innovate around?” She pauses. “That’s our goal: to innovate around problems that matter.”

Lathan’s search for “problems that matter”—or, at least, challenges that would allow her to “do something cool”—picked up steam at age 16, when she arrived at Swarthmore to begin an early college career. She self-created a special major—biopsychology and mathematics—that let her dig into science, math, and the mind. She got swept up in the anti-apartheid movement that had its grip on campus. She logged plenty of hours on the rugby field. And she hung out in the genetics lab studying fruit flies—for fun.

“My lack of focus—or, should I say, my multidisciplinary tendencies—were apparent even then.” She laughs. “I was just always looking for interesting things to do.”

After graduating from Swarthmore, her passion for discovery led her to a year of research in Paris, and then back to the United States, where she enrolled at MIT, concurrently completing a master’s in aeronautics and astronautics and a Ph.D. in neuroscience. With her hard-earned degrees in hand, she accepted a professorship at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. But just as she was about to receive tenure, in 1999, she decided to abandon the predictable world of academia for a life in R&D—an environment more suited to her “multidisciplinary tendencies.”

Thirteen years later and a year after taking the neurobehavioral assessment software to Greenland, the software has been tested in controlled environments from the arctic to the tropics. Lathan and her team are now testing the software with marines returning from Afghanistan. It’s touted for its ability to quickly gauge a user’s reaction time, spatial process, memory, and responses to multiple-choice questions. And, as long as military personnel have a standard mobile device and a stylus, it’s as easy to use as a game on your mobile phone.

But launching this product in the military sphere is just the beginning, Lathan believes.

“What excites me is that it has the potential to monitor the cognitive health of anyone,” she says. “So I see this system as having a tremendous impact beyond military injury.”

How far-reaching might this new software be? That’s a question—like most questions—that Lathan is very eager to explore.

Email This Page

Email This Page