From Rowdy Youngster to Public Historian

Because of impromptu stops during childhood road trips, Allison Marsh ’98 is now a public historian.

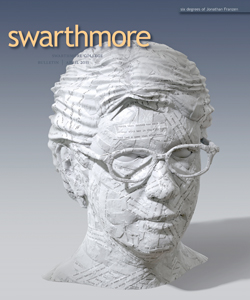

Allison Marsh (left) with colleague Gabi Kuenzli, preparing to tour the silver mines of Cerra Rico in Potosi, Bolivia.

Allison Marsh ’98 stumbled upon industrial America while playing in the backseat of her family’s station wagon during road trips. To quell the rowdy youngster and her sisters, their father would stop the car to visit factory sites and public monuments along the highway.

“We’d all pile out of the car, and my dad would knock on the door and say, ‘We need a tour,’” Marsh chuckles. “That’s how we toured all sorts of bizarre places like the tunnels of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.”

Little did Marsh know that these impromptu pit stops would dictate much of her future career as a professor of public history at the University of South Carolina (USC). An expert on 20th-century technology, Marsh’s research specializes in the cultural and industrial significance of factory tours in American history. Marsh, a double major in engineering and history, also teaches modern U.S. history and the history of science and technology to undergraduates and supervises the museum studies program for graduate students.

Marsh’s research explores a broad spectrum of industrial and public facilities that offer regularly scheduled tours. She has studied their rise, which began in the 1880s, visiting factories in multiple industries such as food, automobile, and mail-order catalogues, in addition to dams, canals, and mines. “What I’m very interested in is a factory where you go out onto the factory floor and see people working,” Marsh says.

Growing up in Richmond, Va., Marsh was no stranger to industrial manufacturing and the mass production that spread through the state capital during her childhood.

“A big second-grade field trip in my elementary school was the Philip Morris cigarette factory,” Marsh recalls. “I can’t imagine that happening now.”

A couple decades later, an older Marsh found herself researching court documents in the archives of tobacco companies under litigation. “It was a goldmine,” she says. “The tobacco companies documented their factory tours as marketing tools.”

“They had different tours marketed to different age groups,” added Marsh. “With schoolchildren, the tours were about tobacco as a crop, about the economy, about how things were made, without actually talking about cigarettes themselves.”

Not surprisingly, her research has revealed that industrial tourism ties into the reputation building and management in which companies have engaged historically. “The tours are not particularly eye-opening, because companies are so conscious of their image and of potential hazards that the tours are sanitized,” she explains. “The purpose of the tours on behalf of the company has always been to sell their image.”

“Aside from the technical question, what my final work comes out as is a history of public relations and advertising,” Marsh concludes about the crisscrossing of professional fields that emerged in her research.

A passionate globetrotter in her leisure time, Marsh has set foot on six continents and dipped her toes in all four oceans (still trying to get to Antarctica), finding that wanderlust has expanded her mindset beyond American borders and culturally enriched her research projects. On a recent vacation in Bolivia to visit a colleague, she toured the local mines for a current book project.

“Because Bolivia doesn’t have the regulations that the United States has, I wanted to see what the working conditions were there,” Marsh says. “They were horrendous and really quite remarkable. I was having tremendous difficulty breathing. For a while there, I feared a little bit for my safety.”

According to Marsh, outsourcing labor to poor, regulation-lax countries has thoroughly impacted the socio-cultural dynamics of factory production. “The further that we get away from these types of working environments, the more disconnected we are from where our products come from.”

“But I’d be careful not to overstate that, because we forget how much of our country is actually involved in this labor force,” she adds, citing a tiny steel-rolling mill located just down her street in Cayce, S.C. “There are a lot of people out there still making things in small factories.”

When Marsh is not conducting research or continent-hopping, she tries to invoke the liberal arts experience in her 100-person lectures at USC, a large state university. Swarthmore has informed her teaching style to emphasize critical thinking and thoughtful dialogue in class. “I ask open-ended questions and offer creative assignments and discussions,” she says. “I expect everyone to learn through voicing their positions, challenging others and their responses.”

“Students either love me or hate me,” she chuckles, explaining that her end-of-the-year evaluations are often “bipolar.” According to Marsh, her students often remark that her lecture was the first one that made them think. “You either get the students who have their eyes opened to a broader world or those people who are fighting against that night and day,” she says.

Marsh is currently working on a book titled The Ultimate Vacation: Watching Other People Work, a history of factory tours in America from 1890–1940 that aggregates all of her research. In addition, she is conceptualizing a museum exhibit in support of the book, which is slated to open in January 2012.

Email This Page

Email This Page