Velvet & Steel

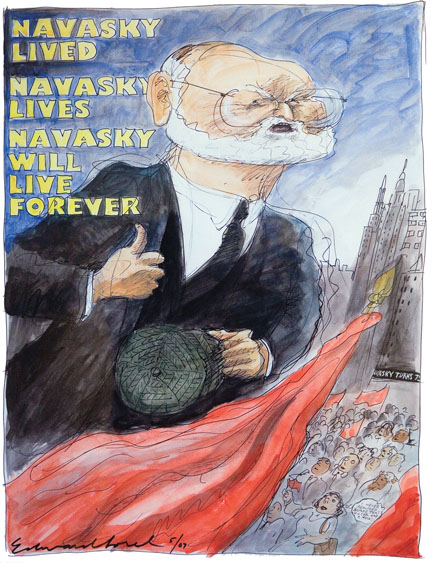

A caricature of Navasky by his friend Edward Sorel, based on a famous poster of Vladimir Lenin, hangs in his living room—a gift for Navasky’s 75th birthday.

VICTOR NAVASKY ENJOYS A GOOD FIGHT: a boxing match, a debate, a gentlemanly duel, his preferred weapon a barbed article in a journal of opinion.

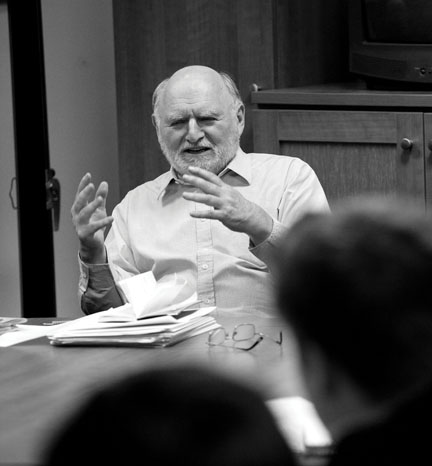

Navasky, the publisher emeritus and former editor of The Nation and now professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, is not pugnacious but temperate in demeanor. He is interested in controversy, but he is not a controversialist. He is at home in the public sphere, the realm of argument and counterargument. “He can be in the fray and stand above it at the same time,” says his close friend E.L. Doctorow, the novelist.

According to Katrina vanden Heuvel, his successor as editor and publisher at The Nation, Navasky is velvet—but he is velvet over steel. “There’s this genial temperament—but it masks a steeliness, which I speak of with affection, but it cannot be ignored,” she says, adding, “You cannot be editor [here] without having a strong inner core.”

Victor and I have coffee at the Navaskys’ Upper West Side apartment, a converted two-story artist’s studio with constant northern light, decorated with oil paintings by Victor’s wife, Anne (Annie to everyone who adores her, and she is widely adored). She interrupts: “I’ve never sat in on an interview with you. I have a question.

“You’ve been attacked, publicly—even called a self-hating Jew.” This was after The Nation published a column by the satirist Gore Vidal suggesting that certain Jewish neoconservatives should register as foreign agents for Israel. “Did that hurt you?” Anne asks.

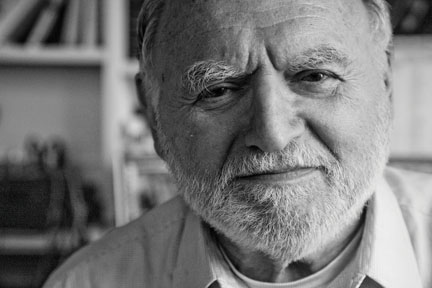

Navasky’s most distinguishing physical characteristic is his very round face (“moon-faced,” he’s been called). Encircling it are a white beard and a horseshoe of hair. He smiles. “Doesn’t hurt me. Naturally, when you get a letter saying you’re a piece of snot or a barrel of slime, it doesn’t make you feel good, but you figure the person is crazy.”

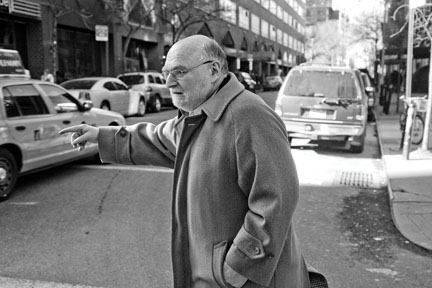

AT 77, NAVASKY WALKS SLIGHTLY BENT, as if against the wind, and he has spent much of his career so leaning. His tenure at The Nation began during the Carter years and ended in the second Bush’s second term. Throughout much of that time, The Nation’s pages offered a shelter for leftist thought, a refuge from prevailing political winds.

The Nation is, in fact, the nation’s oldest weekly magazine—started in 1865. An outgrowth of the abolitionist movement, it inherited the subscription list for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. According to its founding prospectus, The Nation was to “make an earnest effort to bring to the discussion of political and social questions a really critical spirit, and to wage war upon the vices of violence, exaggeration, and misrepresentation by which so much of the political writing of the day is marred.”

The magazine is, at its best and as Navasky has described it, “a debating ground between liberals and radicals.” But Navasky was never an obvious candidate to edit and then own it.

“Most people start out young on the left and move to the center, or they start off in the liberal camp and move into the conservative camp,” his friend Doctorow says. “But the arc of his life has been just the opposite. He started off as a centrist and became more and more of a dissident, in my view.”

Describing his politics during the Vietnam War, Navasky writes in his 2005 memoir A Matter of Opinion: “I was not a tax withholder, I had no beard, I was not even a regular demonstrator. But whatever progressive politics meant, I had them. I was, I guess, what would be called a left-liberal, although I never thought of myself as all that left. I believed in civil rights and civil liberties, I favored racial integration, I thought responsibility for the international tensions of the Cold War was equally distributed between the United States and the U.S.S.R., and I opposed the Vietnam War.”

Navasky stamped The Nation with his resistance to Cold War politics and his concern for free speech and other civil liberties—“That’s certainly the issue closest to his heart,” says Nation editorial board member Philip Green ’54, professor emeritus of government at Smith College and now a visiting professor at The New School. Green points to The Nation’s advertising policy as emblematic of Navasky’s leadership. The policy stipulates: “[W]e start with strong presumption against banning advertisers because we disapprove of, or even abhor, their political or social views. But we reserve (and exercise) the right to attack them in our editorial columns.”

Navasky exercised such rights as editor of The Nation beginning in 1978. Then, while on a sabbatical in 1994, he got a call: The Nation's then-owner, Arthur Carter, wanted to sell. Navasky agreed to purchase the money-losing magazine for a million dollars that he didn’t have and would have to raise. As good practice for his new career entreating investors, “I went out and persuaded my wife [a stockbroker] this was a wise thing to do,” he says. Navasky served as publisher and editorial director from 1995 until he sold the magazine to his chosen successor, vanden Heuvel, in 2005.

“Why would you want to own a magazine that is losing $500,000 a year and sign on the dotted line for a million dollars you don’t have, payable at 6 percent interest? But it worked out,” Navasky says. The Nation’s circulation nearly doubled during the George W. Bush years, peaking at 186,691, proving once again the magazine’s counter-cyclical adage: “If it’s bad for the country, it’s good for The Nation.”

“I had been told that in its 140-odd year history, The Nation had made money for three years; I never could find out which three years,” Navasky tells me. “But for the first time, we were making money, so I was able to pass it on at a time when the magazine was growing. We were technically breaking even. We even had to pay a modest income tax my last year. It was a semi-joke because I had to send a letter of apology to the shareholders, because I’d told them they would get a tax loss.”

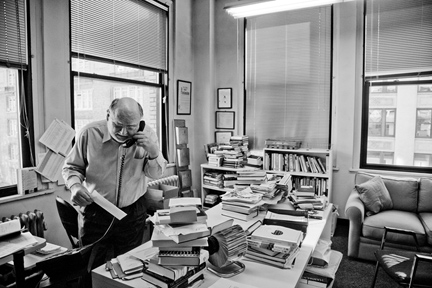

“DON'T TELL ANYONE,” NAVASKY SAYS TO ME—this is, after pleasantries, the first thing he says to me—“but I’m a person with five offices. What I mainly do is look for papers that are in another office. I can’t find anything.”

“I’m a person with five offices. What I mainly do is look for papers that are in another office,” Navasky says.

Navasky is self-deprecating, but he is also serious. When he cannot find something, his eyes bug, his mouth opens, and he drops his arms, stretched open, palms up, insistently, as they are empty. “This is his favorite expression,” Mary Schilling, his long-time assistant, says.

At his three home offices, one in Manhattan and two at a vacation home in the foothills of the Berkshires—part of a shared, 120-acre community, comprising 13 separately owned houses but with the bulk of the land held in common (“Really, it’s more of a middle-class convenience than a ’60s commune,” Navasky told The New York Times last summer.)—Navasky writes. He has written three nonfiction books—the National Book Award winner, Naming Names, on the 1950s Hollywood blacklist; Kennedy Justice, on the Justice Department under Robert Kennedy; and, most recently, A Matter of Opinion, both a memoir and meditation on the journal of opinion and winner of the George Polk Book Award. Navasky, whose writing is characterized by clarity, charm, and force of argument, is contemplating writing another book, about political cartoons and caricatures.

Navasky is also co-author with Christopher Cerf of The Experts Speak: The Definitive Compendium of Authoritative Misinformation (“the first collection of unadulterated, fully authenticated, false expertise”) and, a follow-up collection, Mission Accomplished! Or How We Won the War in Iraq: The Experts Speak.

At his Columbia office, Navasky is the Delacorte Professor, director of the Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism, and chairman of the Columbia Journalism Review, a magazine on the media. Of the magazine, he says: “It’s a time for it to grow and prosper and make a difference like it’s never been able to do before. Its main job is media monitoring and criticism, but it is also supposed to think about how we are going to fix this field which is broken,” Navasky says.

At his Nation office, Navasky attends weekly editorial meetings and writes occasional pieces. “The joke is I’m the obituary writer because I’ve written obituaries for Paul Newman and Studs Terkel—all these people I had inveigled into the magazine who are dying off.”

“People say, ‘I don’t get Victor. Can you explain him?’ I say, ‘No,’” says Philip Green, who’s known Navasky since kindergarten.

“He’s often hard to read because he doesn’t reveal his anxieties, his fears. He told me once he’s had many sleepless nights, but you don’t see that in him when you’re working with him,” says vanden Heuvel.

Navasky carries himself with a certain reserve and can seem unavailable, when in fact he makes a habit of being available and always, even when he was editor of The Nation, he answers his own phone. This habit of responsiveness can startle people, particularly when it is paired with his habit of listening.

There is also, at times, a brusqueness or gruffness, but it is overshadowed by a bountiful generosity, described by Navasky’s friends—and there are many—again and again. “He has many friends, more friends possibly than anybody I know. And if you talk to any of those people, I think you will find that they will tell you that Victor has reached out to help them at some point in their lives and careers,” says Roger Youman ’53, a former editor of TV Guide who now teaches with Navasky at Columbia.

Navasky enjoys watching boxing, but he cannot make a fist. He has rheumatoid arthritis and has long coped with a certain degree of pain. After a Western-trained doctor prescribed 27 injections of gold—“G-O-L-D, gold”—Navasky consulted another doctor who had studied under Dr. Shyam Singha, a practitioner of alternative medicine. “He shook my hand and he said, ‘Jesus you have a lot of rage inside of you.’ He said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this,’” Navasky recalls.

I would not call Navasky an angry man, far from it, but there does beat beneath his calm, quite rational exterior a palatable intensity.

The author of three nonfiction books, Navasky is thinking of writing another about the power of political cartoons. (Read related article: The Art of Controversy).

(For his arthritis, Navasky for a time consulted directly with Dr. Singha himself. Among the good doctor’s prescriptions: a two-week fast, with instructions to eat 16 grilled oranges and eight pounds of grapes a day and nightly steaming hot baths with salts, followed by icy cold showers. Navasky was also told “to conduct an orchestra every day in front of a mirror, naked.” He did it.)

(He is very funny when he tells me about Dr. Singha: “I have a one-act play in my head about him.” Navasky, who twice won Swarthmore’s one-act play competition, co-wrote with Richard Lingeman, his colleague at The Nation, a play about Clinton impeachment prosecutor Kenneth Starr, Starr’s Last Tape, produced at the Berkshire Theater Festival in 1999.)

In understanding Navasky, one must above all understand that he is at heart a satirist, which is not the same thing as a humorist. A satirist exposes the absurd and attempts to improve society by shaming it; a humorist entertains.

Navasky began his magazine career as co-founder and editor of a long-defunct magazine of satire called Monocle. He retains a satirist’s skepticism and the misfortune of counting fellow satirists as friends—including Calvin Trillin, who famously labeled him, for his nasty habit of underpaying writers, “the wily and parsimonious Victor Navasky.”

“I think he is essentially a good-hearted person,” Trillin tells me. “This is one of his faults. I don’t hear him say very many really nasty, underhanded, snide things about people.”

“He’s also very loyal,” Trillin says. “I know that doesn’t seem to square with his wiliness and his parsimony, but that’s what he is.”

NAVASKY, WHO GREW UP IN NEW YORK, was the first member of his family to graduate from college. In his memoir, he writes: “My father, Macy, should have gone to college but couldn’t because he had to go to work for his father, who had come to New York from Russia in the 1890s and founded a small clothing manufacturing business in New York City’s garment district.” Macy Navasky, a subscriber to both The Nation and The New Republic but “no radical,” sold his share of the family business, the Sturdibilt Co. (formerly Navasky and Sons), “at least, partly, I always assumed, so that I would never have to go into it,” Victor writes.

After graduating from Swarthmore in 1954, one year after the Korean War ended, Navasky was drafted into the Army, where he landed a pseudo-journalistic position at the troop information and education office at Fort Richardson, outside Anchorage. He later used the GI Bill® to attend Yale Law School.

At law school, his journalism education continued. He and friends started Monocle, a “leisurely quarterly of political satire” (it came out twice a year) with the motto, “In the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king.” After graduating, Navasky decided to make Monocle a professional publication and moved it to New York, i.e., his ground-floor apartment. “I’ll never forget that one day his mother was at the window wanting to know if he had any laundry she could do,” says Schilling, Navasky’s current assistant, who also worked with him then. “Victor said, ‘Mother, this is a business,’” Schilling recalls. “Loosely.”

“Every magazine is edited with a typical reader in mind; and Monocle is no exception,” begins the editorial in Monocle’s 1960 preview issue as a professional publication, priced at 60 cents. It featured exquisite, inked illustrations and articles by, among others, Kurt Vonnegut and William F. Buckley, Jr. “Playboy’s [reader] is the young man-about-town; McCall’s is the family; The New Yorker’s is ‘not the old lady from Dubuque’; the Dubuque Monthly Garden News’s is the old lady from Dubuque; Seventeen’s is the teenage girl; and Monocle’s, we have discovered after exhaustive research, is Jack Kennedy.”

A magazine with such a limited audience could not last, and Monocle published its final issue in 1965. As Navasky writes, one investor told him: “Look … you’re a bright young man. Part of being a bright young man is knowing when to quit, when to move on.”

A magazine with such a limited audience could not last, and Monocle published its final issue in 1965. As Navasky writes, one investor told him: “Look … you’re a bright young man. Part of being a bright young man is knowing when to quit, when to move on.”

Navasky moved on. He wrote his first book, Kennedy Justice; worked as a freelance writer; and, in 1970, he accepted a position as an editor at The New York Times Magazine. He was offered the job of travel editor—he was climbing the Times’s ladder—but he did not accept because he had his second book deal for Naming Names by then. He quit to write. In 1978, his tenure at The Nation commenced.

“I view him as a person,” Anne Navasky tells me, “who did what he wanted to do, always. I don’t mean that he didn’t have a lot of terrible stuff that he didn’t like doing involved in it, but that he basically is a man who found what he wanted to do and found a way to do it. I thought it was a good example for our children. All three of them really followed him in that way. They like what they do, and they can see what won’t make them happy and don’t take those roads.”

Their oldest child, Bruno, formerly was a teacher and technology director at a Harlem school; he recently quit to write a novel, and he also designs Web sites. Their daughter, Miri, who has two young sons, makes documentary films. Jenny, a social worker, works with pregnant teenagers.

“They’re all well-occupied,” Victor says, “and none of their occupations are designed to comfort their parents in their old age.”

IT IS NOT SURPRISING THAT THE LONG-TIME EDITOR of The Nation would have courted controversy. The source of it, however, may surprise: The most controversial position Navasky has staked is his continued defense of Alger Hiss, the State Department official accused of spying for the Soviets and convicted of perjury in 1950. Navasky is increasingly alone in his view that the case against Hiss has not been proven. For this view, he has variously been criticized as disingenuous, polemical, or stubborn—and praised for his rectitude.

In Denial: Historians, Communism, and Espionage, a 2003 book by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, depicts Navasky as “a prominent revisionist writer” and also as “determinedly myopic.”

“He really does misunderstand or misstate what’s going on in terms of the history of Soviet espionage,” says Haynes, a historian at the Library of Congress, in an interview. As new evidence from Soviet archives and U.S. government records has emerged, Haynes says, the consensus among historians has shifted from a presumption of Hiss’s innocence to a conviction of his guilt. Navasky never shifted; for his part, he tells me, “I deny that I’m in denial.”

“It’s a mainstream consensus among mainstream historians,” that Hiss is guilty, Navasky concedes. He remains a skeptic, however. In 2007, at New York University, Navasky gave a speech, “Hiss in History,” in which he argued that the case against Hiss has not been proven and outlined the 10 reasons he believes the Hiss case will not go away—including what Navasky describes as a tendency for historians to seize upon the incriminating implications of new evidence and ignore evidence that is exculpatory.

The most controversial position Navasky has staked is his continued defense of Alger Hiss, the State Department official accused of spying for the Soviets and convicted of perjury in 1950. The battle over Hiss is a battle over history, particularly the history of the left. “I think the case against him is deeply flawed,” Navasky says.

The battle over Hiss is a battle over history, particularly the history of the left. The case may seem irrelevant today, but it was a referendum, in the eyes of many, on the integrity of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration—the New Deal and the U.S.-Soviet alliance in World War II and the 1945 Yalta Conference (which Hiss attended). The case against Hiss helped fuel Senator Joseph McCarthy’s rise and that of Richard Nixon, who as a member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, brought Hiss to the witness stand.

“HE DOESN'T LIKE ERROR,” Anne tells me, over coffee at the Navaskys’ apartment. This came up recently, when Anne’s portrait of Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was hung in the National Portrait Gallery, in Washington, D.C. Justice O’Connor was to be at the opening, and Victor had a question for her.

The question is long-standing. In his second year at The Nation in 1979, Navasky obtained an advance copy of President Gerald Ford’s memoir and wrote an article about its contents, quoting, he says, “a few hundred words” from it in his article. The publisher, Harper & Row, which had sold the exclusive right to print excerpts from the memoir, prior to its publication, to Time, sued The Nation for copyright infringement. The case climbed to the Supreme Court, which eventually ruled 6-3 against The Nation.

Victor thinks this was a bad decision, but he is also irked by two words actually immaterial to it. The decision, written by Justice O’Connor, refers to the “purloined manuscript.” The manuscript was not purloined, he tells me. It was given to him by someone who was legally entitled to have it. Purloined generally means it was stolen.

The use of the word purloined “drove him crazy,” Anne says. “It didn’t drive me crazy,” Victor responds. “I just wanted you to ask her about it. Just ask her what you do if you get a fact wrong that’s not material to the decision. Like,” he addresses me, “if they said you had blonde hair and you don’t have blonde hair” (I am a brunette).

At the opening night party at the Portrait Gallery, Victor couldn’t get to Justice O’Connor but Justice Stephen Breyer would do. “I said, ‘What do you do if a justice gets something wrong? How do you correct it?’ He said, ‘Send a letter to the court, and we’ll correct it.’ I said, ‘What about 20 years after the fact?’” It seems, in such circumstances, that a statute of limitations would apply.

It is getting late: Anne has to go to work, and Victor has a meeting at The Nation. Victor and I leave the apartment together. We take the cast-iron elevator with the elevator man down to the street. Outside, Navasky immediately yells, “Taxi!” and, in a rush, shuffle-runs to it. He calls over his shoulder, “Can I drop you?” It is a characteristically generous offer. But I am traveling uptown and he downtown so I politely decline, as politely as I can in a shout to someone already on his way.

Elizabeth Redden ’05 is an M.F.A. student in nonfiction writing at Columbia University and a former reporter for Inside Higher Ed in Washington.

Email This Page

Email This Page