Rebel Energy

George Lakey is unstoppable in his quest for peace and justice.

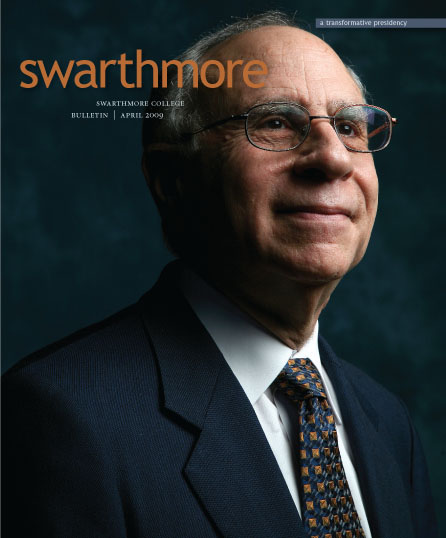

George Lakey — Eugene M. Lang Visiting Professor for Issues of Social Change and Peace and Conflict Studies.

A couple of hours after Barack Obama had been sworn into office seemed to be a more-than-appropriate time to be interviewing George Lakey, a lifelong activist for peace and conflict resolution and civil rights through nonviolent means. Lakey is currently in his third year as Eugene M. Lang Visiting Professor for Issues of Social Change and Peace and Conflict Studies. “Today is really quite a day,” he said, beaming.

Lakey, 71, spoke of his father, a former slate miner, who had passed away two days earlier at age 95. During the 1952 presidential campaign, in a moment of wishful thinking, Lakey’s father had sparked a fierce argument during lunch with his workmates by expressing regret that Ralph Bunche, undersecretary general to the United Nations and highest African American public official in the country, was not running for president. He would have liked to vote for Bunche.

“He was the only one who took that side,” Lakey said. “That was then, and this is now. My dad was so on my mind as I watched the swearing-in this morning.”

Lakey, a Quaker, was active as a campaigner and organizer in the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement. He co-founded the Movement for a New Society, initiated the Philadelphia Jobs With Peace Campaign, and created and organized the Campaign to Stop the B-1 Bomber and Promote Peace Conversion. He founded and served as executive director of Training for Change, a Philadelphia organization that stands up for justice, peace, the environment, and nonviolent change. He has led more than 1,500 training workshops on five continents for groups including homeless people, therapists, prisoners, West Virginia coal miners, Mohawk Indians, lesbians and gays in Russia, and many more.

He is the author of seven books, including A Manual for Direct Action—known as the “Bible” of direct action by southern civil rights activists of the 1960s.

In 2008, he received the Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Prize from the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Previously, he was also honored by the Bread and Roses Community Fund with the Paul Robeson Award for Social Justice as well as the national Giraffe Award for “sticking his neck out for the public good.”

Which five words best describe you?

Rebel, visionary, curious, warm-hearted

Who is your most-admired political figure?

That would have to be Dr. King or Gandhi. It depends what I need. If I need the American context, it’s King; if I need a more cosmopolitan figure, it’s Gandhi.

How do you choose your issues?

I ask myself the question, “What does social change need right now?” and tune into the current moment in history to find a need that isn’t being met. Then, I ask, “If I jump into that, is there a way that I can make it work with my own personal growth agenda, my own journey toward enlightenment?” And I can always find issues out there that are also here, inside me. It’s not hard to find one. I’ll never be without an issue.

Have you ever been in a situation, in which, in retrospect, you might have acted differently?

I was once working with an international peacekeeping organization in the mountains of Thailand, training people to enter areas of conflict and function as peacekeepers. It was an extremely dangerous mission, and the participants were anxious about whether they’d survive. But I didn’t take their anxiety into account. I took the kinds of chances I’d usually take—I’m a risk taker, that’s the nature of my temperament. Even though the participants didn’t learn all they should have learned during the training, they became so bonded that their bonding carried them through the assignment.

In 1990, Lakey (above, third from right) was smuggled into Burma under the guns of the Burmese dictatorship to assist student freedom fighters, who, although also soldiers, took a course on nonviolent struggle against the dictatorship. Living in the dorm of a “jungle university” that the students had organized within a guerilla encampment in the Burmese jungle, Lakey and his Quaker colleague Michael Beer (second from right) received two meals a day and slept on bamboo mats next to a bomb shelter.

What are the essential components for effecting nonviolent change?

We have to figure out how to apply the power of nonviolent action to very varied situations. What works in civil rights doesn’t necessarily work in national defense. What works for national defense doesn’t necessarily apply to terrorism. I believe that a lot of the issues that puzzle us present ripe opportunities for considering how to apply nonviolent action. But it always needs to be done with imagination and humility, rather than a simple-minded transfer of the techniques from one situation to another. We discuss this in the class I’m currently teaching on Nonviolent Responses to Terrorism.

What are your plans for the future?

I’d love to make a dent in the issue of class during the next 20 years or so. For all the strides we’ve made over the years, especially around race and gender, U.S. culture remains fairly clueless about problems of class. Whether rich, middle class, or poor, everyone is hurt by a class society, but only a few people know what’s really hurting them.

How do you enjoy spending leisure time?

I love to play piano for Broadway sing-alongs—in living rooms filled with people singing the golden oldies of Broadway. I also walk in the Crum for exercise with my iPod playing classical music and sometimes folk, jazz, or Broadway songs for company.

Do you have any notable habits?

I take an 18-minute nap every afternoon on my office floor. I’m a vegetarian. As a great-grandfather, I enjoy romping with three little boys, ages 5, 4, and 2. They can romp longer than I can.

How about a favorite book?

There are a bunch, but one that leaps out is The Lazy Man’s Guide to Enlightenment by Thaddeus Golas—a wonderful book! It basically says you don’t have to go to a cave in the Himalayas and starve yourself to find enlightenment. It’s also available to the “lazy” man—and, presumably, woman.

What are you currently writing about?

I’m writing a book on Norway as an example of a society that used to have a very harsh class structure—with overriding poverty, and so on—but that has gone way beyond the United States in terms of cleaning that up and addressing class. I’ve taken research trips to Norway, studying the Norwegians as a kind of convenient, small laboratory to show that people can roll up their sleeves and tackle class.

Have you considered writing an autobiography?

I am writing a memoir, and, although I’ve always kept journals, I thought I’d start with what’s in my head, and then use the journals later. Three years after I started, it’s still coming out of my head. My writing coach said that’s to be expected. He said, “You may find that the more you excavate, the more becomes available.”

Editor’s note: Click here to listen to or download a transcription of George Lakey’s lecture “Post-election Reflection: Where Do We Go From Here”?

Email This Page

Email This Page