Carbon Pricing

The Paris Agreement set the goal for the world to keep global warming well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, with an aspirational goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius. For us to meet that goal, greater than 80% of remaining fossil fuels must remain unburnt, and that will require a dramatic transformation of our food, transportation, industrial, electric, and heating systems. All of those transformations become politically and economically possible with a sufficiently high price on carbon.

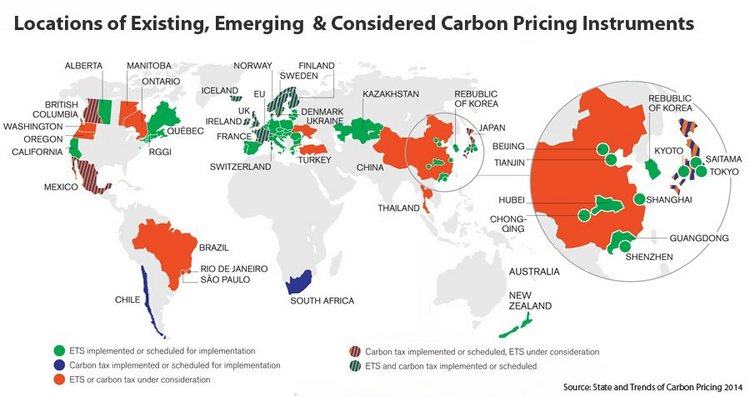

A large number of national and local governments around the world price carbon, through either a carbon fee or an emissions trading system (also known as “cap-and-trade”). An increasing number of private companies are implementing internal carbon pricing and institutions of higher learning are just beginning to do so. These carbon pricing systems have been effective at reducing emissions with no measurable negative economic impact. Even so, prices globally are currently too low. In order to meet the goals set forth in the Paris agreement, carbon prices need to be more widespread, and need to be set higher.

Read the Carbon Pricing Watch 2017 report summarizing the state of carbon pricing schemes globally.

- Policy Design

-

Carbon fees function by assessing a fee on sources of carbon, generally at the point of extraction or the point of import of a fossil fuel in proportion to the carbon that will be emitted when that fuel is burned. That price is then passed onto consumers through higher prices.

In an emissions trading system (or “cap-and-trade” system) large point sources of emissions, such as power plants, must obtain tradable permits in proportion to the company’s emissions. The permits may be distributed for free, auctioned, sold, or a combination. Allowing trading in permits allows for greater abatement at lower cost, in the same way as a carbon fee. The number of permits determines the market price of carbon. The fewer the permits the higher the price.

In either system, there are a number of variables to consider:

Price: A higher price will reduce emissions more sharply and provide more revenue but also impose greater costs of compliance. The optimal price should aim to maximize the benefits of reducing emissions with due consideration of the costs imposed on producers and consumers.

Coverage: A good policy must cover all types of greenhouse gases and must cover all large emitting industries.

Revenue use: The possibilities for use of revenue are numerous, but some of the most popular options are to return it all to households in a monthly dividend; to reduce other taxes proportionately in a tax swap; to support individuals and industries that will be challenged as the economy transitions, such as coal miners; to support renewable energy and decarbonization research, development, and deployment, and other possibilities.

- The Social Cost of Carbon

-

Activities that emit greenhouse gases contribute to climate change impacts and impose costs that are distributed globally, and not directly paid by emitters. Since they don’t pay the costs, it is difficult to motivate large scale reductions in extraction and emission of carbon. Carbon pricing schemes are strategies to make those in the supply chain of fossil fuels pay for the damages that their fossil fuels cause.

Estimates of the social cost of carbon range widely because many impacts of climate change are difficult to predict and difficult to quantify. A calculation of how much an additional metric ton of CO2 adds to these costs is imprecise and there is widespread disagreement about the estimates.

The EPA published a widely-cited estimate of the social cost of carbon at around $38 per metric ton of CO2 in 2016. Their calculation includes decreases in agricultural productivity, human health costs, flood damages, and changes in energy system costs like heating and air conditioning. The EPA’s social cost of carbon estimate increases slightly each year, to account for the non-linear worsening of climate impacts as we continue to emit more carbon.

Read about the EPA's estimate of the social cost of carbon.

The EPA's analysis is generally considered an extremely conservative estimate of the social cost of carbon, because it disregards many costs that are difficult to predict, quantify or monetize. Some of these omitted damages include soil erosion, fires, loss of ecosystem services, spread of pests and pathogens, violent conflict, mass displacement, and ocean acidification.

- Read an analysis that incorporates the impact of climate on economic growth, and estimates a cost of $220 per ton CO2.

- Read an analysis of some of the threats of climate change that are omitted from the EPA's estimate.

- Internal Carbon Pricing in Higher Education

-

Swarthmore is among a small group of schools with internal carbon prices. Yale’s Carbon Charge is piloting multiple structures for an internal price to find the most effective policy for emissions reduction at a university. Vassar incorporates a shadow price and robust life cycle cost analysis policy into its decision making.

We are working to share the lessons and best practices learned on our campus and help other institutions institute carbon pricing. In particular, we are optimistic about the replicability of a shadow price in many institutional contexts.

- Read a white paper proposing Swarthmore's internal Carbon Charge by Swarthmore faculty and staff.

- Read a white paper on Internal Carbon Pricing at a Small Liberal Arts College by Vassar and the Environmental Defense Fund.

- Visit Yale's Carbon Charge program website.

- Read a white paper on the proposal for the Yale Carbon Charge Project.

- Internal Carbon Pricing in the Private Sector

-

The CDP reports that 607 companies currently use an internal carbon price. A handful, like Microsoft, levy charges on branches of a company, while many more use shadow prices to influence decision making, particularly in allocation of research and development resources.

The most common reason for implementing an internal price is to prepare a company for national-level carbon prices where the company operates, so they are more common among companies that make long-term capital investments and that are highly carbon-exposed.

Learn more in the CPD’s 2017 annual report on internal carbon prices in the private sector.