1923

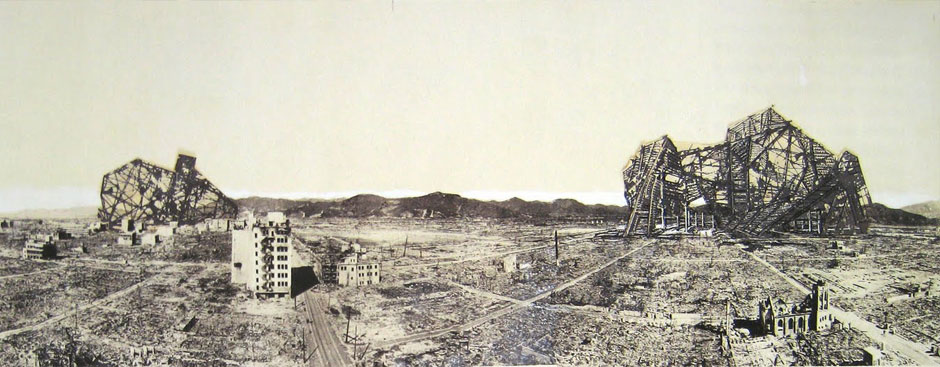

In the early period after the atomic bomb, an anti-nuclear movement emerged in Japan, fueled by the frequent testing of nuclear weapons and international conflicts. In the 1960s, the Metabolist movement, a post-war Japanese architectural movement that fused ideas about architectural megastructures with those of organic biological growth, spurred Isozaki to design "Hiroshima Ruined Again in the Future," in which mega structures grow over the charred landscape of Hiroshima. The Japanese intellectuals experienced a period of very intense and diverse debates, wrapped up in the socially turbulent postwar era

.1945

The newer generations of Japan have not forgotten the disaster, but might perceive it with a different focus. Economic development and tourism promotion in Hiroshima and Nagasaki triggered bitter memories as well as calls for peace, hope and a brighter future. Consequently, in 1977 the May Flower Festival of Hiroshima was born. According to Hiroshima Traces, "the sixth of August is a day of mourning and prayer for the dead... It has been characterized as inert and silent. In contrast, the May Flower Festival is seen as a day to joyfully glorify the living. It is dynamic, potent, vigorous, and animated" (Yoneyama, 1999, p.61). As Yoneyama wrote, "At least in its official representation, Hiroshima will continue to be transformed into a site of pleasure and urban entertainment... we will then be able to enjoy the pleasures of peace without discomfort about the potential for wars or nuclear terror" (1999, p.64).

1995

Since the post WWII baby boom, Japan has exhibited a steady decline in its birthrate. In 1975, for the first time since WWII, the birthrate dropped below the rate of 2.07 births per woman that is necessary for Japan to maintain a stable population (Takeo, 2013). In addition to fewer births, elderly are now living longer lives than ever, causing a demographic shift toward an aging nation. One would believe that care for the aging would have been a high priority in Japan. The aftermath of the 1995 Kobe Earthquake showed the contrary. The elderly, especially lower income elderly citizens, experienced the most hardship in the wake of the disaster.

Over half of the 4,512 deaths were of people sixty and older. Reasons for this are multiple: many elderly lived in areas of the city with lower quality infrastructure, and in badly maintained old wooden buildings with structural damage. In the process of evacuating to emergency shelters, elderly were often lumped together, creating communities of dependent people at a time when most volunteers and doctors were preoccupied with assessing the immediate needs of those in critical care. Although the experiences of the elderly were not the direct intentional outcomes of any one person, it does not make their collective story worth any less. In quite the opposite way, the lack of care for the elderly highlights precisely how entire groups of people can become forgotten in the chaos of a disaster.

2011

The insufficient amount of temporary housing, however, did allow for architects to create their own solutions. One architect in particular who gained international fame for building temporary structures was Ban Shigeru. Although his buildings were not necessarily catered to the elderly, he did make a conscious effort to support minority populations. In this case, he decided to work with a community of Vietnamese refugees. Together with volunteer students he built a church in five weeks, and a small neighborhood of 52 m2 houses, each for under $2000, using readily available materials such as paper tubes and beer crates.