Lantern Slides of E. Raymond Wilson

Luke Arnone, Swarthmore College, Class of 2014

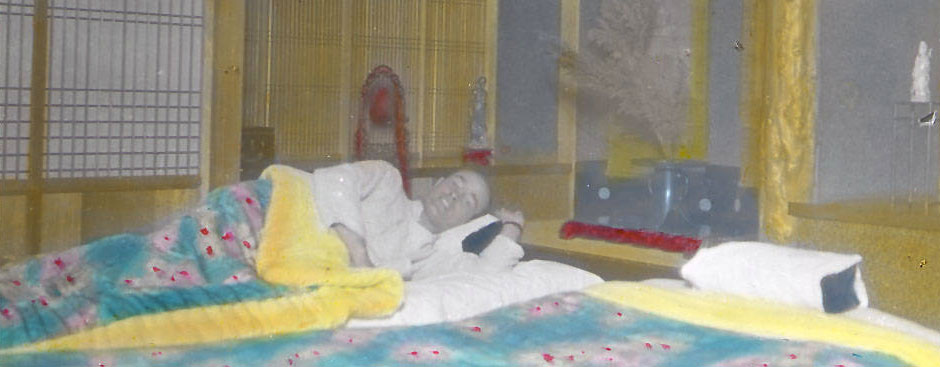

These two lantern slides show E. Raymond Wilson and a friend in the context of a Japanese-style inn (ryokan). They have been hand-colored just like many of the professionally shot slides of landscapes and native people in Wilson's lantern slide collection, but their subject matter is distinctly more candid. In Figure 1, Wilson and his companion are served a meal, donning matching robes (yukata) provided by the inn and eating seated in the Japanese style. In Figure 2, Wilson can be seen relaxing under the covers of a futon, which would have been laid out on the floor after the meal had been cleared away.These two slides are unique within the Wilson collection in that they show Westerners in a Japanese environment.

E. Raymond Wilson was granted funds to visit Japan for a year in 1926. His trip was funded by the Japanese Brotherhood Scholarship, which was given out for the purpose of strengthening understanding between the United States and Japan. While there, much like a modern study abroad experience, Wilson lived with a host family and attended classes at the Imperial University. As he was particularly interested in the agricultural aspects of Japanese life, he also traveled extensively around Japan. (Yoder 2006) It is likely on these travels that he and a friend stopped to stay at a ryokan, where these slides were taken.

Ryokan were - and are today - spaces which exist outside the rhythm of everyday life, both in their adherence to simplicity and ritual, and in their "stubborn refusal to change" to keep pace with the increasing rapidity of the modern world. (Black 2000) Some have spa-like public and private baths (often built over hot springs), and a rough comparison can be drawn between the two facilities.

In the period during which Wilson visited Japan, cultural exchange between the United States and Japan had been limited to small, elite, yet disorganized set of societies, themselves a product of small-scale Japanese student exchanges with the US since the late 19th century. (Austin 2011) Lantern slides were sold as tourist objects in Japan, and this is likely how Wilson came into possession of the majority of the slides that were donated to the Peace Collection. (Yoder 2006) Independent Japanese photographers created lantern slides of quintessentially "Japanese" subjects - Mt. Fuji, cherry blossoms, Buddhist priests, peasants—and sold these to tourists. Two of these photographers, Futaba & Co. and T. Takagi, both of Kobe, are credited with many of Wilsons lantern slides in the Peace Collection. In looking at these slides, we can compare how Japanese entrepreneurs chose to package Japanese culture with the candid juxtaposition of Western visitors in a Japanese environment.

The vast majority of the lantern slides in the E. Raymond Wilson collection have a carefully staged feel about them, a postcard-like atmosphere that removes their specificity of moment - they are a packaged version of the experience of visiting Japan, as opposed to documentation of an individual journey. The slides' similarity to postcards is no coincidence, for they were sold - like postcards or other visual memorabilia - in sets to visitors from the West. While Wilson visited many, if not all, of the sites pictured in his lantern slides, he certainly did not capture the actual images in the slides attributed to T. Takagi or Futaba. Considering the various authors of the images in the Wilson collection, it bears noting the illusory nature of photographic "truth." The slides that Wilson purchased, as opposed to capturing himself, show Japan through the lens of a Japanese apparatus that packaged culture for Western consumption. They are especially valuable for understanding what aspects of their culture Japanese image-makers wished to showcase for Western (and even domestic) audiences, and the ways in which those differ from the ways in which Japanese culture was processed by Western visitors themselves. The two slides that capture Wilson in Japan serves to offer a contrast, suggesting how Western tourists packaged Japanese culture for themselves and for viewers back in America. Additionally, we get a glimpse of aspects of Japanese culture not self-selected for documentation, for example, interiors of a traditional inn.

We can read a kind of fascination in the post-processing—the hand-tinting of the image reveals what details in the image the maker (in this case, probably someone commissioned by Wilson) wished to accentuate: it is the objects especially foreign to Westerners. The kimono and sash of the woman serving dinner, the blanket on the futon, and the serving dishes and food held in chopsticks are all strongly delineated and colored. Unlike most of the Wilson slides that were produced by Futaba or Takagi, which attempt at least some degree of naturalistic representation of color and composition, here while some objects leap off the picture plane, Wilson and his companion almost blend into the background. They serve to contextualize the experience for other Westerners, to whom these slides would likely have been intended to be shown, and emphasize the otherness of the experiences the images captures.

Such private scenes as these are not fodder for official documentation, but they were the environments in which Wilson found himself in the course of his travels. It is noteworthy that these images depict scenes that would appear mundane to a Japanese viewer, yet to an American, these versions of basic human processes would seem highly exotic. The affective impact of performing a basic ritual in such a distinctly different manner from which one is accustomed is an understandable cause for the impulse to document. There are a variety of explanations for why we do not find similar scenes in the remainder of the Wilson lantern slides. It is possible that Japanese photographers and other domestic cultural interpreters considered images of private life to be too banal to be worth packaging for intellectual export; it is conceivable that they did not imagine the practices of eating and sleeping to hold sufficient mystique for the Western eye. To a visiting American, however, the ways in which one dined or rested in Japan would be terrifically novel, and certainly worth documenting - with a kind of incredulous expression on one's face.