Shugendō Ritual Garment

Dijia Chen, Bryn Mawr College Class of 2016

This garment is the upper robe of a suzukake, the ritual garment worn by yamabushi, mountain ascetics of Shugendō. The robe was donated by Bryn Mawr College alumna Helen B. Chapin, who was a foundational scholar in East Asian Studies in the United States. Chapin traveled to China, Japan, and Korea in the 1920s and early 1930s, during which she garnered a great collection of East Asian artifacts. She studied at Yakushiji, a prominent Buddhist temple, at Nara during her stays in Japan, and gained prestige as a Buddhist scholar.

Shugendō is a highly syncretic religion that gradually took form in the ninth and tenth centuries when the Japanese folk tradition of mountain veneration incorporated elements from shamanism, esoteric Buddhism, Taoism, and several other religious influences (Earhart, 2001, p.2-3). Embodying a distinct blend of Shinto, the indigenous kami (deity) worship, and Buddhism, an imported religion, Shugendō has played an active role in shaping the worldview and the religious life of the Japanese people.

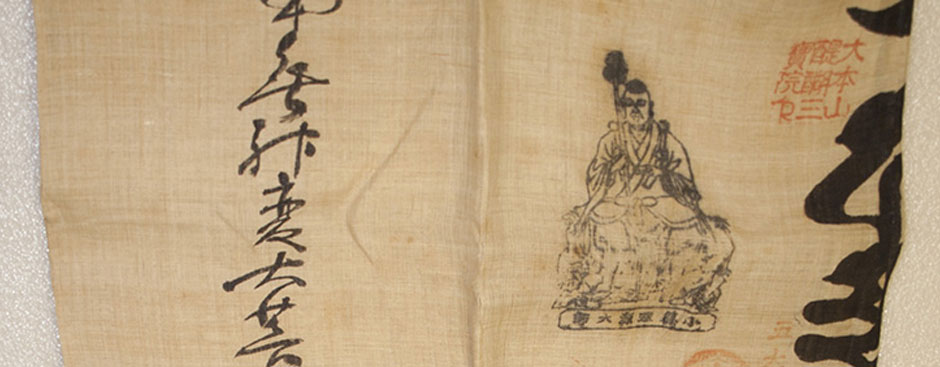

The red seal to the left of the collar (Figure 1) reads "Daihonzan Daigo Sanbōin," identifying the garment to be for Daigoji Temple's Sanbōin, a major Shugendō center of the Tōzan branch affiliated with the Shingon esoteric Buddhist sect. The calligraphy on the right sleeve says "Namu Shōbō Rigen Daishi" (Figure 2), invoking the name of the legendary founder of the Tōzan sect and Daigoji temple, Rigen (832-909), whose portrait in holy garment appears at the left shoulder (Figure 3). The calligraphy on the left sleeve "Namu Jinben Daibosatsu" (Figure 4) and the portrait on the right shoulder (Figure 5) invoke En no Gyōja (b.634), the legendary founder of Shugendō. Shugendō was influenced by folk ancestor worship, and many of its founders—including the two figures—were accredited with legends, deified, and enshrined as objects of worship (Miyake, 2001, p.118-119).

In ancient Japanese religious thought, mountains were considered to be the dwelling place of the spirits of the dead, the liminal space between this world and the other world, and the axis connecting heaven and earth or the cosmos itself. Living beings on a mountain were thus also considered to be sacred and liminal. Additionally, Shingon Buddhism introduced the idea of attaining spiritual powers through practicing asceticism in the mountains. Combining these influences, the yamabushi dressed in a 16-piece attire that included suzukake and climbed sacred mountains while performing stringent rituals of seclusion, fasting, meditation, chanting mantras, and austere acts of endurance. The suzukake symbolized the Shingon view of the cosmos, with the upper robe representing the diamond mandala and the trousers the womb mandala. Together, the rituals and attire prepared their bodies to transcend restrictions of this world and enter a liminal state when they could become "half man and half deity" (Miyake, 2001, p. 79-80).

The yamabushi were believed to inherently possess Buddha nature but are yet unaware, having the potential to awaken their Buddha nature through mountain asceticism. Thus, mountain austerities are often initiation rites that represent a cycle of death and rebirth. At Kōtaku Temple on Mt. Haguro, the initiates undergo training called the practices of rokudō (six worlds) from August 24th to 31st. Starting with a symbolic funeral for their death as humans in the temple at the foot of the mountain, the initiates of Shugendō ascend Mt. Haguro while engaging in rituals of conception, purification, awakening of Buddha nature, exorcism of bad spirits, binding souls, and ancestor worship. On the last day, they descend from the mountain and finally perform the ritual of rebirth as Buddhas by giving out a "birth-cry" and jumping over a sacred fire (Miyake, 2001, p.91).

The fire of rebirth is in the same style as the mukaebi (welcome fire) used in Obon (festival of the dead) to welcome the spirits of the ancestors who have come back to visit the living (Miyake, 2001, p.91). In fact, as Japanese religion scholar H. Byron Earhart writes, "much of the content and texture of Japanese folk religion was produced and shaped after the pattern created and diffused by Shugendō" (2001, p.5). In the course of history, Shugendō had laid the foundation of the Japanese worldview that combines different religious lineages and maintained the tradition to influence the Japanese way of life. The above similarity is most likely not coincidental, and the religious ritual and its symbolic meaning have remained in history and been applied in present day. Most notable is the use of okuribi, which is the "departure fire" and counterpart of mukaebi, in commemoration of the lives lost during disasters. In Hiroshima, there is an annual tōrō nagashi, in which participants float paper lanterns down a river by the A-bomb Dome to guide the spirits of the victims gathered at the Dome back to the other world; and in Kobe Luminarie, an annual event to commemorate the 1995 Kobe Earthquake, the guiding fires are symbolized by the brilliant lighting installations. The belief and practice that stemmed from traditional religion have remained in history and undergone change in the modern society to integrate into the lives of Japanese people.