| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

About Samatha Power

Samantha Power is a Professor of Human Rights Practice at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. Her book "A Problem From Hell": America and the Age of Genocide was awarded the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction, among others. In May, she gave this commencement speech at the University of Santa Clara Law School. Her complete text appears in The Nation. |

|

| |

'm always a little surprised to be asked to be a commencement speaker. It is clear from your roster of past speakers that you could have lined up an Attorney General or a Cabinet Secretary to help you usher in your post-law school lives. But inexplicably you chose me: a woman who was a decidedly average student in law school, who never took the Bar Exam and who, despite shelling out $100,000 bucks, still can't quite decide what she wants to do with her life. I can't imagine why, after your three years in law school, any of you would identify with these particular qualities... 'm always a little surprised to be asked to be a commencement speaker. It is clear from your roster of past speakers that you could have lined up an Attorney General or a Cabinet Secretary to help you usher in your post-law school lives. But inexplicably you chose me: a woman who was a decidedly average student in law school, who never took the Bar Exam and who, despite shelling out $100,000 bucks, still can't quite decide what she wants to do with her life. I can't imagine why, after your three years in law school, any of you would identify with these particular qualities...

. . .

So why am I standing before you today? Well, first, I don't know about you, but I have found many of the recent criticisms of U.S. foreign policy as unconstructive as U.S. foreign policy itself. Therefore, I'd feel like a slacker if I stayed buried in the archives, working on another book, when an occasion like this one offered me an opportunity to make some small contribution to an adult conversation about America's role in the world. But second, much more importantly, people actually listen to commencement speeches. It's the weirdest thing - they really do!

In 2002, I gave my first ever commencement address at Swarthmore College. A Problem from Hell, which had struggled to find a publisher, had just come out. It had won no prizes and at that point it had been read only by my very large Irish Catholic family (accounting for thriving early sales, I might add). I was so nervous about the speech that the night before I couldn't even cure my butterflies with the age-old Irish remedy of multiple stiff drinks. I don't honestly remember much of what I said, and if I went back and read the speech today, it would make me cringe. But I know I called upon Swarthmore students to become "upstanders" rather than bystanders in their post-college lives. I survived the speech, hightailed it out of town, and haven't been back to that campus since.

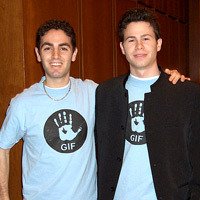

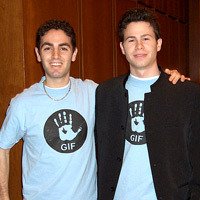

| Genocide Intervention Network founders Mark Hanis '05 and Andrew Sniderman '05 in the Hart Senate Building on April 6th, 2005, to launch GI-Net's 100 Days of Action. |

|

|

| |

In 2004, around the ten year anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda (a genocide in which 800,000 Rwandan Tutsi were exterminated), and a couple of years after my Swarthmore speech, a ragged trio of Swarthmore students showed up at my office in Cambridge. They had come to inform me that they had heard my graduation speech and they intended to apply its lessons with regard to the ongoing genocide in Darfur. If the lesson of the twentieth century was that the American people had abetted U.S. governmental indifference to genocide, a twenty-two year old senior named Mark Hanis told me, he and his friends would show Washington that the American people cared. If the lesson of the twentieth century was that states were quick to feed the victims of genocide, by delivering humanitarian aid, but unwilling to actually use force to stop the murders, he and his friends would raise money not for relief but to help pay for protection forces.

| |

| Stephanie Nyombayire '08 speaks on college campuses around the country about the personal experiences that have driven her to take action as a GI-Net representative. |

|

| |

I was skeptical. But Stephanie Nyombayire, an 18-year-old Swarthmore freshman from Rwanda who had lost more than one hundred members of her family in the genocide, put it to me simply: "Professor Power, if the genocidaires in my country were able to kill a million people in a hundred days in 1994," she said, "why can't we students raise a million dollars in a hundred days?" Why can't we?

The students told me that their new, Swarthmore-based Genocide Intervention Fund would raise the money and write a check to the African Union, which had sent peacekeepers to Darfur, but which was seriously ill-equipped. The money would help them buy the flak jackets, helmets, and fuel they needed to move around Darfur and protect civilians.

I looked at the students blankly. As a now-responsible adult, I was afraid to encourage their charge toward windmills, but I was not about to discourage them either. As I drove home from the café where the students had eventually pinned me down, Stephanie's question stayed with me: "Why can't we?" And then I remembered a commencement address I had heard at Yale the year before I graduated. The political cartoonist Gary Trudeau had spoken, and he had urged students to "ask the impertinent questions." His message had stuck with me. My message had somehow stuck with these Swarthmore kids. Damn, I thought, I'd like to give a few more of these commencement addresses. I hope somebody asks me.

Now in the hopes that you'll take up this challenge, I'm going to tell you five personal stories, each of which offers a lesson. I figure if I give you five, I increase my odds of saying something memorable. One of these lessons might just stick.

. . .

What lessons did Samantha Power offer? Read her complete remarks in The Nation.

| |

| |

|

|

| The Genocide Intervention Network envisions a world in which the global community is willing and able to protect civilians from genocide and mass atrocities. Its current mission is to empower individuals and communities with the tools to prevent and stop genocide. |

|

|

| |

|

'm always a little surprised to be asked to be a commencement speaker. It is clear from your roster of past speakers that you could have lined up an Attorney General or a Cabinet Secretary to help you usher in your post-law school lives. But inexplicably you chose me: a woman who was a decidedly average student in law school, who never took the Bar Exam and who, despite shelling out $100,000 bucks, still can't quite decide what she wants to do with her life. I can't imagine why, after your three years in law school, any of you would identify with these particular qualities...

'm always a little surprised to be asked to be a commencement speaker. It is clear from your roster of past speakers that you could have lined up an Attorney General or a Cabinet Secretary to help you usher in your post-law school lives. But inexplicably you chose me: a woman who was a decidedly average student in law school, who never took the Bar Exam and who, despite shelling out $100,000 bucks, still can't quite decide what she wants to do with her life. I can't imagine why, after your three years in law school, any of you would identify with these particular qualities...